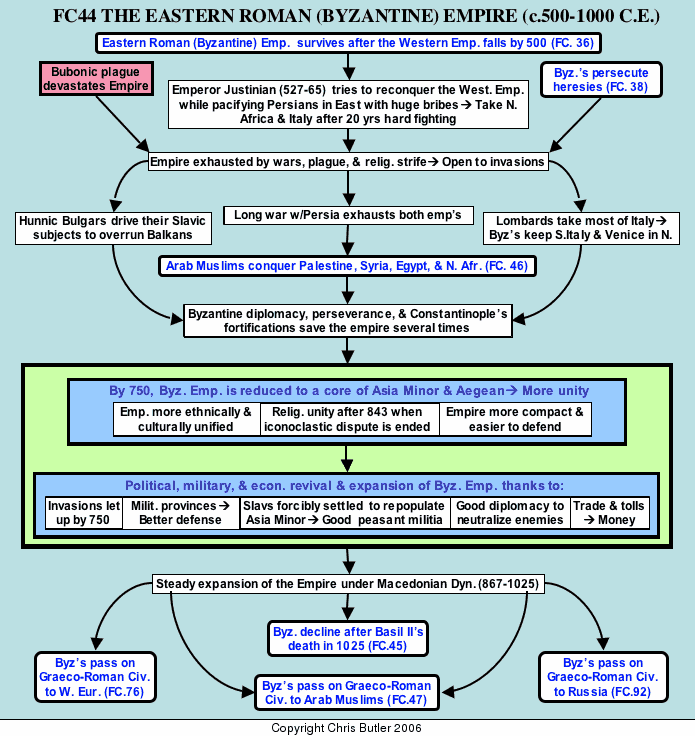

FC44The Byzantine Empire (c.500-1025)

Introduction: the "Second Rome"

When we study the Middle Ages, we tend to focus on Western Europe since it is the homeland of Western Civilization. However, this gives us a distorted view of medieval history, for Western Europe was little more than a backwoods frontier compared to the real centers of civilization further east. It is here that we are concerned with one of those eastern cultures, Byzantium, and its contributions to civilization. Cities provide the central focus of civilization, and no civilization seemed to center on a city more than Byzantine civilization did on Byzantium, or Constantinople as it was known after its refounding by Constantine in 330 C.E.

Constantinople's location at the narrow juncture between the Aegean and Black Seas was ideal for controlling trade between those two bodies of water as well as the trade routes that converged there to link Asia and Europe. The city itself was blessed by nature, with water bordering two of its three sides. This provided it with easy defense and an excellent harbor known as the Golden Horn. The natural advantages of the city were further enhanced by human ingenuity. The harbor was protected from invasion by a massive chain stretched across its entrance. The landward side had a huge triple set of walls to protect it. Down through the centuries, when all else failed, that chain and set of walls kept Constantinople safe from invasions. Many times all that seemed to remain of the empire was Constantinople itself. But as long as the city survived, the empire also survived to bounce back and recover its old territories.

Inside its walls, Constantinople contained some of the most marvelous sights in the civilized world. Many of these reflected the Roman heritage that the Byzantines were carrying on: aqueducts, sewers, public baths, and street planning. Other sights, in particular some 100 churches, reminded one that Constantinople was a very Christian city. Still other sights reflected oriental influences: the bustling markets offering goods from all over the civilized world, the palace complex of the Boucoleon with its reception halls, mechanically levitating thrones, imperial gardens, and silk factories. Much of the Byzantines' success in dealing with their less sophisticated neighbors was due to their ability to dazzle visitors with such wonders.

Turmoil, crisis, and the transition from Roman to Byzantine Empire (527-7l7 C.E.)

While we refer to the Byzantine Empire, people in the Middle Ages never lost sight of the fact that this was the eastern half of the Roman Empire that had survived the barbarian invasions of the fifth century C.E. As a result, they called them "Romans". Both the terms Byzantine and Roman have some truth to them. They were the direct heirs of the Roman Empire and did carry on the remains of that empire for some 1000 years after the fall of the western half of the Empire. However, for all intents and purposes, it became a predominantly Greek empire and culture as the Middle Ages progressed. Its subjects spoke Greek, worshipped in what came to be the Greek Orthodox Church, and wore beards in the Greek fashion. They even argued and fought over religion in much the same way the ancient Greeks had argued and fought over politics.

The turning point in this transition from Roman to Byzantine civilization came in the reign of Justinian I (527-565). We have seen how this "last of the Roman emperors" tried to reclaim the Western empire. In the process, he virtually wrecked the eastern empire with the high cost in money and manpower for his wars and tribute to keep the Persians quiet in the east. Two other factors merely added to the damage: persecution of Monophysite heretics in Syria, Palestine and Egypt which alienated much of the population against the central government and bad luck in the form of a devastating plague which decimated the population. When Justinian died, the empire may have looked strong on the map, but in reality it was exhausted and in desperate need of a rest. Unfortunately, rest was the last thing the empire would get.

The next two centuries would see the Byzantines constantly beset by waves of invaders coming from the north, the east, and the west. The very fact that the Empire survived at all seems a miracle considering the troubles it endured. In the West, the first wave of invaders, the Lombards poured into Italy in 568, only three years after Justinian's death, and set off centuries of fighting between themselves, Byzantines, Franks, and even Arabs. The Byzantines did manage to hold onto Ravenna and Venice in the north and southern Italy and Sicily to the south. However, except for those outposts, the Roman Empire in the West was gone.

A more serious threat to the empire's existence came from the east. Around 600 C.E., the chronic hostility between Byzantines and Persians erupted into a titanic life and death struggle that would last a quarter of a century. The Persians overran Syria, Palestine, and Egypt while the nomadic Avars in the north were rampaging through Greece and the rest of the Balkan Peninsula. At the low point of the war, Constantinople was virtually all that remained of the empire in the east, and it had to withstand a siege by the combined Persian and Avar armies. Fortunately, the stout walls of Constantinople held fast against the enemy assaults, and a new hero, the emperor Heraclius, emerged to save the empire. Leaving Constantinople to defend itself, he struck deep into Persia to draw its armies away from his capital. In a series of resounding victories, the Persians were crushed and the Byzantine Empire saved. However, in the process, both empires had been thoroughly exhausted.

Unfortunately, right on the tail of this war a much more serious threat suddenly appeared. The Arabs, united and inspired by their new religion, Islam, swept in like a desert storm, toppling Persian and Byzantine resistance like a house of cards. The Persian Empire was subjugated in its entirety. Meanwhile, the Byzantines watched as Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa all fell to the Arabs. Not content with these conquests, the Arabs pressed on through Asia Minor toward the coveted prize of Constantinople itself. Once again, the city's fortifications held out, and after a four-year siege, the invaders were driven back. One reason for this victory was the use of a new secret weapon, Greek Fire, which sent the Arab ships into wild uncontrollable flames. This chemical would be a mainstay of the Byzantine defense and a highly guarded state secret for centuries to come. We still do not know exactly what was in it, although it was probably some sort of petroleum compound.

In 7l7 C.E., a new emperor, Leo III, from Isauria in southern Asia Minor, came to the throne. The empire's situation at the time was not very hopeful, for another huge Arab army was descending on Constantinople. As in times past, Byzantine fortifications and Greek Fire took their toll. By the following spring, the Arabs were in full retreat. This was the last time the Arabs would besiege Constantinople, and the end of this siege symbolized the beginning of a period of stabilization for the empire's frontiers and internal development. Fighting would continue with the Arabs, but mainly in the form of sporadic border raids rather than massive invasions.

The Byzantines also faced serious threats in the north from both Asiatic nomads and their Slavic subjects whom they drove in front of them. Two of these nomadic tribes, first the Avars, and later the Bulgars, waged relentless warfare on the Byzantines, mercilessly devastating the Balkan Peninsula in their raids. The Balkans virtually dropped out of Byzantine control and the light of history for nearly two centuries as they were inundated with Slavic invaders. To the north, a powerful Bulgar kingdom proved to be nearly as serious a threat as the Arabs for the next 350 years. Eventually, the Bulgars would settle down, adopt Christianity, and even briefly be conquered by the Byzantines. But for now, they were one more major problem to be overcome.

By 750 C.E., thanks to some astute diplomacy that turned their enemies against one another, perseverance in the face of disaster, and the fortifications of Constantinople, the Byzantines had survived, often against incredible odds, both foreign invasions and internal religious strive. However, they had been stripped of all their lands except for Asia Minor, part of Thrace around Constantinople, Sicily, and parts of Italy. And they were still surrounded by very aggressive neighbors. No longer was it a Roman Empire in anything but name and a few Italian holdings. From this point on, it was truly a Byzantine Empire.

Unfortunately, just as outside pressures from the Arabs were starting to ease, a cloud of religious controversy descended upon the empire. The new issue, Iconoclasm, concerned the icons (religious images) the Church used to depict Christ and the saints. The iconoclasts thought that the use and veneration of these images was idolatry. The iconodules said icons were needed to instruct the illiterate masses in the teachings of Christianity. Leo III and several of his successors were iconoclasts and moved to abolish this form of idolatry by seizing the icons and destroying them.

As one might expect in an era when religion was such a vital issue to both the individual and the state, Iconoclasm touched off some violent reactions from people attached to the icons. Riots swept through the cities of the empire. Relations were strained with the Church in Western Europe, which also defended the icons. Palace intrigues and murders centered largely on the icon issue. When an iconodule empress, Irene came to the throne (blinding her own son in order to seize power), she disbanded several of the best regiments of the army since their troops were mainly iconoclasts. This, of course, damaged the empire's ability to defend itself and invited raids from its neighbors. After over a century of this turmoil (726-843), the images were restored and the empire could pursue a more stable course undisturbed by major religious controversies.

The imperial centuries (c.750-1025)

The disturbances of the seventh and eighth centuries left a very different empire from the one that Justinian had ruled. The most noticeable difference was that the empire was much smaller, having been stripped of Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa. While this deprived the Byzantine government of valuable revenues, it also made the empire much more compact and easier to defend since it was now confined mainly to Asia Minor and the Balkan Peninsula.

The recent turmoil also made the Byzantine Empire a more ethnically, culturally, and religiously united realm. The largely Aramaic speaking peoples and Monophysite "heretics" of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt were now under Muslim control. This left a predominantly Greek speaking populace more or less united by the same religious views once the Iconoclasm struggle had settled down. The empire may have been smaller, but it was also more cohesive.

The upheavals caused by two centuries of foreign invasions forced the Byzantines to adapt their society, government, and defenses to what seemed to be a continuous state of crisis. There were five main factors that helped the empire revive. First of all, after 750 C.E., the pressure from invasions let up somewhat, although it was still an ever-present menace. Second, the Byzantines pursued an active policy of repopulating Asia Minor that had been devastated by the wars of the previous centuries. The main policy they followed to this end was to take hundreds of thousands of the Slavic people who had overrun the Balkans and resettle them on the empty lands in Asia Minor. These people were hard working industrious folk who became loyal subjects and excellent soldiers for the Byzantine state. No single policy probably did more to revive the fortunes of the Byzantine Empire than this resettlement policy.

A third factor aiding Byzantine revival had to do with the administration and defense of the empire, which needed serious overhauling. Back in the third century, Diocletian had created separate civil and military officials in his provinces to cut down on the possibility of revolt. However, the constant threat of invasions faced by the Byzantines forced them to abandon Diocletian's system and create military provinces called themes run by military governors ( strategoi). The emperors did cut down on the possibility of revolt somewhat by having the tax collectors answer directly to them. This still left the governors enough power and freedom to defend their provinces. The governors needed professional help in running the provinces, which was provided by an excellent civil service, possibly the best of any medieval state.

Given the high priority that defense should be given, it should come as no surprise that the Byzantine army also carried on the ancient Roman tradition of excellence. However, the nature of the warfare the Byzantines faced, (usually quick hit and run border raids), differed considerably from the Roman style of warfare. As a result, the army's core consisted of highly mobile and versatile regiments of cavalry known as cataphracts. The cataphract was heavily armed and could rely on shock tactics similar to those of western knights to drive back the enemy. But he was also armed with a bow and could function as a horse archer when necessary. The Byzantines also fielded light cavalry plus heavy and light infantry who were useful in different types of terrain, especially hills and mountains. Recruitment was done according to village, each village being responsible for supplying a quota of peasants armed and ready for service. This system was superior to that of Western Europe where the more troublesome and ambitious nobles were responsible for and in control of defense.

Another important aspect of Byzantine defense was the navy, since the empire contained so much coastline. At its height, the Byzantine navy consisted of some 200 ships of the line called dromons. These were galleys armed with rams as well as catapults or siphons for launching the deadly Greek Fire. Unfortunately, the high expense of maintaining a fleet and the rebellious nature of the sailors caused the Byzantine government to neglect the navy from time to time. Such periods of a weak navy allowed the resurgence of piracy and enemy navies, in particular those of the Arabs.

The fourth factor helping the Byzantines was their diplomacy and the fact that they were the only people of the Middle Ages who made a systematic study of their enemies and how they fought. They produced several military manuals detailing precisely what formations, maneuvers, and tactics to use against the heavy knights of Western Europe as opposed to the mobile light cavalry used by their enemies to the north and east. The Byzantines had to be more scientific about these matters because they were usually outnumbered by their enemies and had to rely on every trick or stratagem possible.

The first goal they generally pursued was to avoid a war if at all possible. As a result, the Byzantines were very skillful in diplomacy, especially against the less sophisticated cultures to the west and north. The first principle of Byzantine diplomacy was to turn two neighbors against each other and let them fight for Byzantine interests even though they might not realize they were doing just that. Naturally the neighbors who were duped into this kind of behavior would be somewhat bitter about it. Byzantium's neighbors, especially those in Western Europe, denounced the Byzantines as cowards for their strategies. Even today the word "byzantine" is used to denote vicious intrigue. However, looking at the Byzantines' situation, we can understand why their behavior and concepts of war and heroism differed so much from those of Western Europe. When they had to fight, they did so very well. But they were masters of conserving their meager human resources and relying on other methods to attain their goals.

Finally, such a well-run empire with a highly trained civil service, army, and navy, required a healthy economy to support it. The invasions of the seventh and eighth centuries severely damaged the Byzantine economy. Most of its cities were reduced to little more than fortified strongholds to protect the surrounding peasants. In spite of this, Byzantine wealth was legendary, especially to the relatively simple peoples surrounding the empire. Such contemporary writers as Liutprand of Cremona tell of being thoroughly dazzled by the wealth and splendor of Constantinople. The capital city was the crossroads of much of the trade of the civilized world at that time.

A ten per cent toll on all imported goods from this trade raised sizable revenues. The government also kept monopolies on such goods as silk, grain, and weapons. Furthermore, it kept tight control on all the craft guilds, strictly regulating their quality of workmanship, wages, prices, and competition. As stifling to their economy as these measures may seem, they did protect the somewhat fragile industries and trade in the unstable period of the early Middle Ages. As a result of this protection, Byzantine industries flourished and its goods were among the most highly prized and sought after in the Mediterranean. Later, when trade and industry revived elsewhere, strict Byzantine controls would work against its people in more competitive markets.

The firm foundations of administration, defense, and economy laid by the Isaurian and Amorian dynasties (7l7-867) bore fruit under the Macedonian dynasty, which took the Byzantine Empire to the height of its power. The century and a half from 867 to 1025 saw a succession of generally excellent emperors who maintained the stability of the empire internally while expanding its borders. In 863, a major Arab invasion was annihilated at Poson, which set the stage for the steady advance of Byzantine armies against the Muslims. Even Antioch, one of the five original patriarchates of the Church lost to the Muslims in the 600's, was recovered. The Byzantines even had their eyes set on retaking the Holy Land and Jerusalem. In the north, the emperor Basil II waged relentless warfare against the Bulgarians, eliminating their kingdom entirely, and earning the title "Bulgar slayer". By Basil's death in 1025, the Byzantine Empire's borders extended all the way to the Danube River in the north and the borders of Palestine in the south. The Byzantines were definitely the super power of the Near East, but after Basil II's death everything started going wrong.

Our debt to the Byzantines

Byzantine civilization created little that was new or unique, being largely absorbed in religious matters or copying the literary forms of ancient Greece. However, in such an age of violence and confusion, the Byzantines did make invaluable contributions to civilization. First of all, Byzantine missionaries spread Greek Orthodox Christianity and civilization northward. Eastern Europe, especially Russia, was heavily influenced by Byzantine architecture, religion, and the Cyrillic alphabet. For example, the "onion domes" atop many Russian Churches testify to Byzantine influence. Orthodox Christianity has also had a profound and lasting impact on the Russian people down through the centuries to the present day, even surviving and outlasting official discouragement from the communist regime that held sway for nearly 75 years.

Second, the Byzantines passed Greek civilization, in particular its math and science, on to the Muslim Arabs. They in turn took the Greek heritage, added their own ingenious touches (such as the invention of algebra), and passed it on to Western Europe by way of Muslim Spain. This helped lay the foundations of our own scientific tradition.

Finally, the Byzantines directly passed much of ancient Greek culture to Western Europe during the Renaissance. Also, the Byzantines, just by holding back so many nomadic invaders from the East through the centuries, allowed Western Europe’s culture survive and develop in relative peace. Many writers from the West, hostile to the Byzantines for historical reasons discussed above, have downplayed and criticized the role the Byzantines have played in the history of our civilization. This is unfortunate, since, during the Early Middle Ages in particular, the Byzantines did more than their share in the preservation and advance of civilization