FC127Total War (1914-1918)

At first there will be increased slaughter--increased slaughter on so terrible a scale as to render it impossible to get troops to push the battle to a decisive issue. They will try to, thinking that they are fighting under the old conditions, & they will learn such a lesson that they will abandon the attempt forever. Then...we shall have...a long period of continually increasing upon the resources of the combatants...Everybody will be entrenched in the next war.— I.S. Bloch (1897)

You smug faced crowds with kindling eye Who cheer when soldier lads march by Sneak home and pray you'll never know The hell where youth and laughter go.— Siegfried Sassoon

We are ready, and the sooner the better for us.— German General von Moltke

The war of movement (August-September, 1914)

When Europe went to war in 1914, many, although not all, people welcomed it as an opportunity for national glory. Soldiers, especially in Western Europe, also marched, or rather rolled, to war much more quickly than ever before. France alone, with its extensive network of railroads, had 7000 trains, some only eight minutes apart, moving troops to the front. Also, rapid population growth and mechanization from the Industrial Revolution, freed many more men than ever before for war.

Europe also marched to war better armed by far than any previous army in history. Germany seemed particularly armed to the teeth, thanks to the Kruppworks at Essen, Germany, a vast complex of 60 factories with its own police force, fire department, and traffic laws. One new weapon would especially change the face of war. That was the machine gun, which could fire 600 bullets per minute and stop any old-style human wave assaults dead in their tracks, literally. It was the machine gun that would put an end to the illusion of a quick victory in a war of movement--but not at first.

In the opening weeks, the Schlieffen Plan went like clockwork. While stopping a French offensive, known as Plan 17, from driving eastward into Germany, the strong German right flank swept the French, British, and Belgian forces back toward Paris, covering up to 20 miles a day, an exhausting pace for infantry loaded with up to 60 pounds of equipment. In fact, that pace plus the German General von Moltke's weakening of the Western offensive in order to meet a Russian offensive unexpectedly materializing in the East may have doomed the Schlieffen Plan to failure. The French and British allies made their stand to save Paris along the Marne River, many troops being rushed to the front in Paris taxicabs. The allies stood fast and the German offensive ground to a halt. Then, somewhat spontaneously and out of simple survival instinct, the soldiers started digging trenches. The Schlieffen Plan and war of movement had failed. The age of trench warfare had begun along what would ever after be remembered as the Western Front.

The new face of war

Making trench warfare especially bad was the fact that the opposing trenches were generally only 500 yards or less apart. This kept soldiers in constant contact with the enemy and constantly immobilized in the mud trenches to avoid the danger above. This contrasted sharply with previous wars where armies would fight a battle, withdraw, and then regroup for several weeks or months before the next battle. This had given soldiers long breaks from the terrors of battle, a psychological safety net that kept them halfway sane. But that safety net no longer existed as soldiers stayed in constant contact with the enemy and became worn out from battle fatigue, producing a catatonic-like state known popularly as the "thousand yard stare".

Life in the trenches, even during relative lulls in the fighting, was a thoroughly wretched experience. It was hot in summer and especially cold in winter. It was also wet and muddy, giving the soldiers little or no chance to bathe, exposing them to infestations of rats, lice, disease, and infection. One of the worst of these infections was trenchfoot, caused by the soldiers' not being able to remove their socks and boots for long periods of time and often resulting in amputation of the infected foot or leg. The following excerpts from the novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, by Eric Maria Remarque, himself a veteran of the war, capture the misery of life in the trenches.

There are rumors of an offensive. We go up to the front two days earlier than usual. On the way, we pass a shelled schoolhouse. Stacked up against its longer side is a high double wall of yellow, unpolished brand-new coffins. They still smell of fir, and pine, and the forest. There are at least a hundred.

“That's a good preparation for the offensive," says Muller astonished.

“They're for us," growls Detering.

“Don't talk rot" says Kat to him angrily.

“You be thankful if you get so much as a coffin," grins Tjaden, "they'll slip you a waterproof sheet for your old Aunt Sally of a carcass.”

The others jest too, unpleasant jests, but what else can a man do?---The coffins are really for us. The organization surpasses itself in that kind of thing...

We are in low spirits. After we have been in the dug-outs two hours our own shells begin to fall in the trench. This is the third time in four weeks. If it were simply a mistake in aim no one would say anything, but the truth is that the barrels are worn out. The shots are often so uncertain that they land within our own lines. Tonight two of our men were wounded by them.

******

The front is a cage in which we must await fearfully whatever may happen. We lie under the network of arching shells and live in a suspense of uncertainty. Over us Chance hovers. If a shot comes, we can duck, that is all; we neither know nor can determine where it will fall.

It is this Chance that makes us indifferent. A few months ago I was sitting in a dugout playing skat; after a while I stood up and went to visit some friends in another dugout. On my return nothing more was to be seen of the first one, it had been blown to pieces by a direct hit. I went back to the second and arrived just in time to lend a hand digging it out. In the interval it had been buried

It is just as much a matter of chance that I am still alive as that I might have been hit. In a bomb-proof dugout I may be smashed to atoms and in the open may survive ten hours' bombardment unscathed. No soldier outlives a thousand chances. But every soldier believes in Chance and trusts his luck.

******

We must look out for our bread. The rats have become much more numerous lately because the trenches are no longer in good condition. Detering says it is a sure sign of a coming bombardment.

The rats here are particularly repulsive, they are so fat-- the kind we call corpse rats. They have shocking, evil, naked faces, and it is nauseating to see their long, nude tails.

They seem to be mighty hungry. Almost every man has had his bread gnawed. Kropp wrapped his in his waterproof sheet and put it under his head, but he cannot sleep because they run over his face to get at it. Detering meant to outwit them: he fastened a thin wire to the roof and suspended his bread from it. During the night when he switched on his pocket-torch he saw the wire swinging to and fro. On the bread was riding a fat rat.

At last we put a stop to it. We cannot afford to throw the bread away, because already we have practically nothing left to eat in the morning, so we carefully cut off the bits of bread that the animals have gnawed.

The slices we cut off are heaped together in the middle of the floor. Each man takes out his spade and lies down prepared to strike. Detering, Kropp, and Kat hold their pocket-lamps ready.

After a few minutes we hear the first shuffling and tugging. It grows, now it is the sound of many little feet. Then the torches switch on and every man strikes at the heap, which scatters with a rush. The result is good. We toss the bits of rat over the parapet and again lie in wait.

Several times we repeat the process. At last the beasts get wise to it, or perhaps they have scented the blood. They return no more. Nevertheless, before the morning the remainder of the bread on the floor has been carried off.

In the adjoining sector they attacked two large cats and a dog, bit them to death and devoured them.

Next day there is an issue of Edamer cheese. Each man gets almost a quarter of a cheese. In one way that is all to the good, For Edamer is tasty--but in another way it is vile, because the fat red balls have long been a sign of a bad time coming. Our forebodings increase as rum is served out. We drink it of course; but are not greatly comforted.

For days we loaf about and make war on the rats. Ammunition and hand-grenades become more plentiful. We even overhaul the bayonets--that is to say, the ones that have a saw on the blunt edge. If the fellows over there catch a man with one of those he's killed at sight. In the next sector some of our men were found whose noses were cut off and the eyes poked out with their own saw-bayonets. Their mouths and noses were stuffed with sawdust so that they suffocated. Some of the recruits have bayonets of this kind; we take them away and give them the ordinary kind.

But the bayonet has practically lost its importance. It is usually the fashion now to charge with bombs and spades only. The sharpened spade is more handy and many-sided weapon; not only can it be used for jabbing a man under the chin, but is much better for striking with because of its greater weight; and if one hits between the neck and shoulder it easily cleaves as far down as the chest. The bayonet frequently jams on the thrust and then a man has to kick hard on the other fellow's belly to pull it out again; and in the interval he may easily get one himself. And what's more, the blade often gets broken off.

Total War

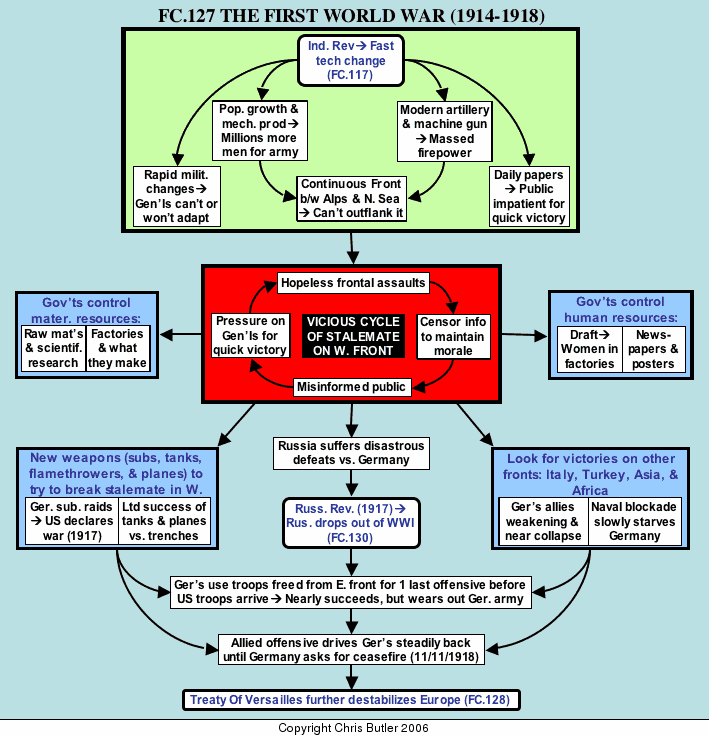

Four factors, all arising from the Industrial Revolution, had totally changed the face of war. First of all, the Industrial Revolution provided enough men (thanks to population growth and the mechanization of many jobs) and firepower (especially the machine gun) to dig and fill opposing trench systems stretching from the Alps to the North Sea, a system several hundred miles in length. The result was the continuous front which neither side could outflank since it was hemmed in by mountains and sea. Unfortunately, the machine gun and faster loading rifle which made the continuous front possible also made the technology of defense superior to that of offense. There was no way that unshielded infantry could get across that murderous area of flying metal known as No Man's Land. That is not to say that people did not try. They did, and with disastrous results.

Third, most generals either did not understand the nature of this new type of warfare or felt they could not afford to accept it. After all, most of these generals, many of whom were quite old, had not been able or willing to keep up on the rapidly changing technological changes transforming warfare in recent years. It is often said that generals are always fighting the last war, and nowhere did this better apply than to the generals of World War I. Before we become too critical, however, it should be pointed out that at no time in history had warfare been so thoroughly revolutionized in so short a time. The machine gun and continuous front had created a whole new ball game, but no one had a rule book by which to play. And so for four years, the generals just fumbled around the best they could while soldiers continued to die.

The fourth factor, also resulting from the Industrial Revolution and complicating matters further, was the media, in particular the newspapers. Never before had the public back home been so well informed about the progress, or lack of it, in a war. The generals had promised a quick victory, and the public and press had a close eye on how well they were doing. In the more democratic countries of France and Britain the generals found themselves under severe pressure by the public and politicians to win the war decisively and quickly. This was especially true of France, since the German lines contained northern France along with the bulk of its industries, and the French public was clamoring to get it back.

All of these factors combined to create a tragic pattern of suicidal frontal assaults that would prolong the stalemate. The casualties would be so horrible that governments modified or censored news coming from the front. This created a misinformed public and media that, thinking victory was within their grasp, would put more pressure on the generals for a quick victory. As a result, there would be more disastrous offensives more censorship to misinform the public, and so on.

Such offensives were usually conceived by generals behind the lines without any clear idea of what the front was really like. Preceding the attack for several days would be a massive bombardment that did a lot less damage than hoped for and which also told the enemy where the attack was coming. As soon as the shelling stopped, the troops went "over the top" into No Man's Land where the obstacles of barbed wire (left undestroyed by the bombardment) and craters (actually created by the bombardment) held them up so that the enemy machine guns (also unharmed since they had been taken to the dugouts below during the shelling) could cut them down. The men who suffered through this living hell often give us its most graphic and poignant descriptions.

“We listen for an eternity to the iron sledgehammers beating on our trench. Percussion and time fuses, 105's, 150's, 210's—all the calibers. Amid this tempest of ruin we instantly recognize the shell that is coming to bury us. As soon as we pick out its dismal howl we look at each other in agony. All curled and shriveled up we crouch under the very weight of its breath. Our helmets clang together, we stagger about like drunks. The beams tremble, a cloud of choking smoke fills the dugout, the candles go out.” — Verdun veteran, 1916

“the ruddy clouds of brick-dust hang over the shelled villages by day and at night the eastern horizon roars and bubbles with light. And everywhere in these desolate places I see the faces and figures of enslaved men, the marching columns pearl-hued with chalky dust on the sweat of their heavy drab clothes; the files of carrying parties laden and staggering in the flickering moonlight of gunfire; the "waves" of assaulting troops lying silent and pale on the tapelines of the jumping-off places

“I crouch with them while the steel glacier rushing by just overhead scrapes away every syllable, every fragment of a message bawled in my ear...I go forward with them...up and down across ground like a huge ruined honeycomb, and my wave melts away, and the second wave comes up, and also melts away, and then the third wave merges into the remnants of the others, and we begin to run forward to catch up with the barrage, gasping and sweating, in bunches, anyhow, every bit of the months of drill and rehearsal forgotten.

“We come to the wire that is uncut, and beyond we see gray coal-scuttle helmets bobbing about...and the loud crackling of machine-guns changes as to a screeching of steam being blown off by a hundred engines, and soon no one is left standing. An hour later our guns are "back on the first objective," and the brigade, with all its hopes and beliefs, has found its grave on those northern slopes of the Somme battlefield.” — Henry Williamson, age 19

“Verdun transformed men's souls. Whoever floundered through this morass full of the shrieking and dying...had passed the last frontier of life, and henceforth bore deep within him the leaden memory of a place that lies between life and death.” — Verdun veteran

The first day's butchery in an offensive, such as the 60,000 British who fell on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, should have been enough to convince the generals to call off the attack. But that would be admitting failure for all their months of plans and preparations. Therefore, the offensives continued, in some cases for months, with the casualties piling up into the hundreds of thousands. Each successive battle followed the same pattern and would continue that way until someone figured out how to solve the problems that the machine gun and continuous front had created. Until that day, it remained stalemate on the Western Front.

New fronts and new weapons

The continuing cycle of stalemate on the Western Front forced the warring powers to realize modern war is total war, demanding activities in all possible directions to sustain their own efforts and wear down those of the enemy. This led to efforts in five areas: control of material resources at home, control of human resources (including the media and morale), continued attempts to break through on the Eastern Front, the search for victory by opening new fronts, thus making it truly a world war, and the search for victory through the development and use of new weapons.

Material and human resources on the home front

World War I devoured enormous amounts of material resources, forcing governments to closely control production and distribution of those resources. Blockaded Germany, in particular, had to ration food strictly. It also controlled mineral resources and even scientific research, which developed synthetic nutrients and ways to derive nitrates from the atmosphere for explosives. France also had to exert strong central control over production, since its industrial north was largely behind German lines, forcing it to rebuild much of its industry further south by 1918.

Human resources had to be controlled to ensure enough men for the front and a labor force for the strategic industries at home. With so many men gone to war, women entered the work place in unprecedented numbers, taking over many occupations previously reserved solely for men before the war, such as secretaries. After the war, when many husbands and fiancées did not return, many women stayed in the workplace, giving them more economic power and eventually the vote. To maintain morale, governments assumed more control of the media, limiting or distorting the information available to the press and public. Governments also actively tried to harness popular support for the war with brightly colored and illustrated posters that glorified the war effort and portrayed the enemy as less than human.

As the homefront became more of an integral part of the total war effort, governments saw enemy factories and civilians as legitimate war targets. In 1915, a German Zeppelin launched a bombing raid on London, killing several people. Although the damage from this raid was small by later standards, it pointed the way for much worse to come for civilians in wartime.

The Eastern Front

Allied hopes for a quick Russian victory in the East were quickly dashed in August 1914 when the Germans annihilated invading Russian forces at Tannenburg. (This was the first and only time allied forces set foot on German soil during the war.) Germany also bolstered Austria against the Russians in the south, causing a much looser version of the Western Front to evolve in the East, since the armies (except Germany's) were less mechanized and thus less successful in stopping a war of movement. The Russians were particularly poorly armed (many of them even without rifles), and their offensives against the German positions met with especially disastrous results. By 1917, Russia, bled white by the war, stood on the verge of revolution.

New Fronts

Each side also tried to divert and drain the enemy's strength by opening up new fronts. Turkey was the first new power to enter the war, in this case, on Germany's side. This threatened to cut off British and French supplies to Russia by way of the Black Sea and prompted a British offensive known as the Gallipoli Campaign. This was one of the worst run operations of the war. At least twice, the British generals had victory within their grasp, but chose to nap or have teatime rather than press their advantage, giving the Turks time to bolster their line. For several months, the allies were pinned down to the beaches until disease and casualties forced them to withdraw.

After this, the main British strategy against the Turks was to stir up and support rebellions. In that regard, one of the most celebrated figures of the war was T.E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, a charismatic figure who succeeded in organizing the Arabs and destabilizing the already decrepit Ottoman Empire. The British issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which promised a Palestinian homeland for the Jews in return for their help. This promise, in conjunction with conflicting promises to the Arabs, would be (and still is) the source of intense conflict in the Middle East.

Italy, despite being part of the Triple Alliance, joined France and Britain in order to take disputed lands from Austria. However, Austria managed to defeat Italy, making it more of a burden to Britain and France, who had to keep it supplied with guns, money, and fuel just to keep it in the war. Meanwhile, Bulgaria joined Germany and Austria in order to take Macedonia from Serbia, which it accomplished quickly. Serbia's British and French allies responded by landing 500,000 men at Salonika, Greece, where they did nothing until 1918, earning it the title of Germany's "biggest internment camp."

Europe's African and Asian colonies were also dragged into the war, making it a truly global war. The British were able to seize Germany's African colonies except for German East Africa. In Asia, the Allies persuaded Japan to attack German holdings and spheres of influence in China. This gave Japan a foothold in China that it would expand in the 1930's, laying the foundations for World War II in Asia. Overall, despite mixed results, Germany's allies gradually weakened as the war dragged on.

There was also the naval front. In the years preceding the war, Germany had built a fleet second only to Britain's. In 1915, the two navies clashed at Jutland. It was an indecisive battle, with Germany getting a slight advantage. But the Kaiser, not wishing to damage his nice new navy, called it into port where the British kept it blockaded for the rest of the war. The blockade was soon extended to all German ports and slowly starved Germany to death.

New Weapons

Meanwhile, each side looked desperately for new weapons to solve the problem of the continuous front. Poison gas and flame-throwers, pioneered by Germany, became all too common and horrible features in trench warfare, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. After the war, the Geneva Convention outlawed both weapons as inhumane. However, two other weapons had a big future in warfare. One was the tank, which gained the allies at least limited success in breaking through enemy trenches. Despite their slowness (3 mph) and unreliability (only half making it to the starting line in their first major battle), tanks shielded allied troops, helping them cross No Man's Land with relatively few casualties.

The airplane, first used for observations of enemy lines, was adapted to combat use, being armed with a machine gun to shoot down other planes. At first, aerial warfare consisted mainly of individual combats (dogfights) between pilots. It was very limited, polite (at least by warfare's standards), and the most glorified aspect of World War I, a sort of chivalry in the skies. Even that changed by war's end, with the allies sending up hundreds of planes to sweep the skies and strafe and bomb the German lines, a strategy that would be developed with much more deadly effect for the next war.

The submarine was Germany's great equalizer in the naval war. While Britain ruled the waves after Jutland, German U-boats (submarines) could still lurk beneath the waves and prey upon allied shipping in retaliation for the blockade on Germany. However, some of the ships Germany sank were from the United States, technically a neutral power but actively trading much needed food and other supplies to France and Britain. While Germany felt justified in sinking any ships supplying its enemies, the United States saw these attacks on its ships as barbaric and unprovoked acts of aggression.

Germany eased up on its attacks for a while to keep America neutral. But in 1917, as the war effort got more desperate, U-boat raids resumed. Then the British intercepted and publicized the Zimmerman Telegram, in which Germany offered Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California to Mexico if it would attack the United States and divert its attention from the war in Europe. American public opinion was outraged, and the United States declared war on Germany in March 1917. That same month another ally, Russia, after three years of defeats and shortages, became engulfed in Revolution.

The end of the "war to end all wars" (1917-18)

Alexander Kerensky's moderate government that replaced the Czar, needing to look legitimate to the outside world, kept Russia in the war, which only weakened it further and led to its overthrow by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in November, 1917. The following March, Lenin signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, taking Russia out of the war while giving up Poland, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Finland. This also freed one million German troops for the Western Front. The question was: Could the addition of the United States compensate for the loss of Russia?

With virtually no standing army when it declared war in 1917, the United States needed a year to mobilize its industrial and military might. Therefore, in 1918, the war became a race to see who could first arrive on the Western Front in force: the newly mobilizing Americans or the Germans freed from the Eastern Front.

At first, the Germans won the race and launched an offensive, attacking with smaller tactical units to punch holes in the enemy lines and drive them back bit by bit. Also, the attacks were not preceded by artillery bombardments that could warn the enemy where the attack was coming. This strategy succeeded in driving the allies back toward Paris. But, as in 1914, the allies, now bolstered by newly arrived American units, stopped the Germans at the Second Battle of the Marne.

Now the allies went on the offensive. Using the very tactics the Germans had just used, the growing numbers of fresh American troops at their disposal and large numbers of tanks to shield their soldiers crossing No Man's Land, they sent the Germans reeling back step by step toward Germany. At the same time, the British blockade was gradually starving the German homeland to the limits of its endurance.

At this point, all the pressures building elsewhere caved in on Germany, as its allies collapsed one by one: first Bulgaria, then Turkey, and finally Austria. Exposed to attack from the south and east, Germany finally asked for an armistice (ceasefire). On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, after one final flurry of artillery fire, the guns fell silent. Here and there, opposing soldiers met in No Man's Land to pay their respects to men who, like themselves, just happened to be wearing different uniforms, and then turned toward home. The First World War was over. However, its effects would be long-lasting and varied, including the Second World War a mere twenty-one years later.