FC71The Black Death and its Impact (c.1300-1450)

And prayers have no power the Plague to stay."— Piers Plowman

Introduction

In the 1300s, Europe entered a

period of turmoil that shook of medieval civilization to its

foundations and paved the way for such aspects of the modern world as

nation states, capitalism, and the Protestant Reformation. Such

periods of transition are rarely easy to endure, and this was no

exception. It was a period which saw recurring famines, outbreaks

of plague, peasant and worker revolts, the rise of religious heresies,

challenges to the Church's authority, and long drawn out wars, in

particular the Hundred Years War between France and England.

Ironically, the problems were largely the result of better farming

methods.

Signs of Growing Stress

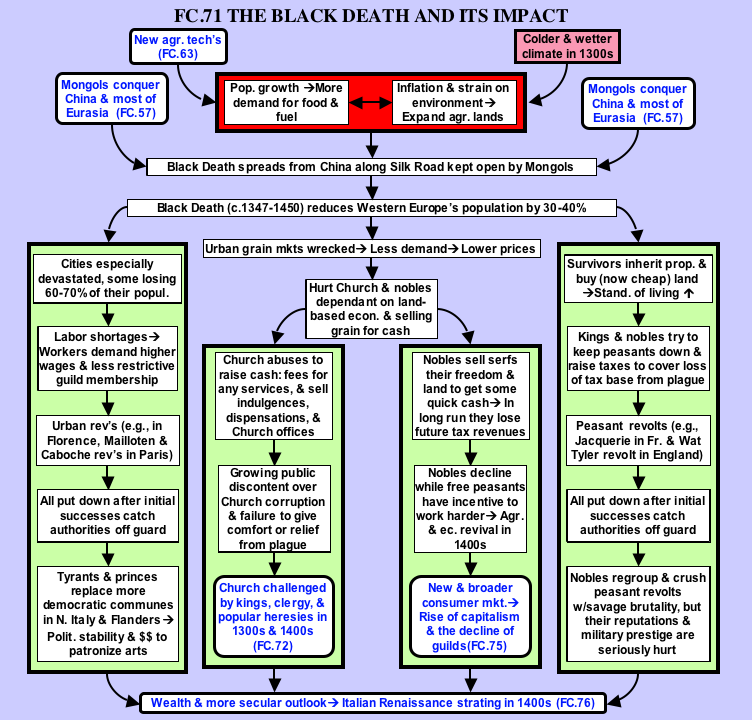

The High Middle Ages had been a time of growth and prosperity. New agricultural techniques had caused a dramatic rise in population, which in turn led to rising demands for food and fuel. This generated inflation and a strain on the environment , which led people to clear more new lands for cultivation. That, in turn, triggered more population growth, and so onAggravating these problems was a change of climate. Apparently, the climate in the High Middle Ages was good, thus making possible that period's prosperity. However, in the 1300's the climate turned colder and wetter than usual, resulting in floods and early frosts. Sources spoke of great famines in 1316 and 1317 and of reports that the Baltic Sea froze over in 1303 and 1316. The resulting malnutrition of the early 1300s made people born during that time especially susceptible to disease, since our immunological systems develop during childhood. This in turn set up the worst of the Middle Ages: the Black Death.

The Coming of the Plague

The Black Death, also known as Bubonic plague, appears to

have arisen in Central Asia in the early 1300's. The most likely

scenario for its spread points to Mongol rulers in Asia who had settled

down from their rampages to establish stable caravan routes from China

to the Black Sea where Italian merchants would trade for the silks and

spices so highly valued in Europe. Ironically, these trade routes

were also the invasion routes of a very different sort.

Apparently, the Asian black rats, which carry the fleas that carry the

plague, burrowed into the caravan's grain sacks and hitched a free ride

across Asia. Rumors had already filtered westward of a terrible

plague that depopulated whole regions of China and India. Rumor

became reality for Europe in 1347 when a Genoese ship pulled into the

Sicilian port of Messina with half its crew dead or dying from

plague. The Black Death had arrived.

The Plague quickly spread death and terror across Europe, sweeping

through Italy in 1347, France in 1348, and the Low Countries, England,

and Scandinavia in 1349. Its pattern was to flare up in the summer and

taper off in the winter, only to flare up again and sweep onwards the

next summer. By 1350, it had pretty well passed on, leaving in

its wake a population decimated by its effects.

Cities, with their crowded unsanitary conditions, generally suffered

worse than the countryside. Although contemporary accounts

generally exaggerated the toll, it was certainly was staggering.

Supposedly 800 people died in Paris each day, 500 a day in Pisa, and up

to 600 a day in Vienna. Some cities lost anywhere from 50-70% of

their populations. Monasteries, also being crowded, suffered

similar death rates. In the countryside where people were more

spread out, maybe 20-30% of the population perished.

All across Europe black flags flew over towns to warn travelers that

the plague was there. Church bells rang constantly to announce

the deaths of citizens until town councils voted to silence their

demoralizing clangor. The Hundred Years War was interrupted by

the plague, and construction on the cathedral in Siena, Italy stopped

and never resumed, a grim memorial to the plague's power.

People, having no idea then of the existence of microbes, were

completely ignorant of the plague's cause. Some, seeing a

correlation between fleas and plague, killed dogs and cats, just giving

the black rats more freedom to spread the disease. Most

explanations of the Black Death concerned divine retribution.

This gave rise to the flagellants, people who would march from town to

town whipping themselves to atone for society's sins. However, as

they spread penitence, they also spread the plague. Therefore,

the authorities outlawed them, as much for the social unrest they

seemed to stir up as for the disease they were spreading. The

most effective way of avoiding the plague was to avoid people who might

carry it, causing those rich enough to flee the towns during the

plague's height in the summer months. In fact, a virtual panic

seized people as husbands abandoned wives, parents abandoned their

children, and even priests and doctors refused to see their

patients. It seemed as if the whole fabric of society was coming

unraveled.

In the absence of any effective remedies, people looked for

scapegoats. Many blamed the Jews whose religion dictated a bit

cleaner lifestyle, which in turn meant less incidence of rats, fleas,

and plague. In some peoples' minds, however, the Jews had

poisoned the wells or made a pact with the devil to cause the Black

Death. The resulting disturbances resembled those accompanying

the First Crusade, with Jews being massacred or burned in their

synagogues. Germany and the Low Countries saw especially bad

outbreaks of such violence, and, by 1350, few Jews remained in those

areas.

The plague hit Europe six more times by 1450, each time with less

severity than before, since more survivors were immune to it. And

those without resistance were weeded out by natural selection.

Still, some 30-40% of Europe's population was lost. Census

figures in England fell from 3.7 million in 1348 to 2.1 million by

1430. Even then, Europe was not free from the Black Death's

ravages, suffering recurrent outbreaks until the early 1700's.

Why it receded is also a matter of controversy, with such theories as

the European brown rat driving out the Asian black rat, tile roofs

replacing thatched ones where rats often lived, and the more deadly

plague microbe, which more readily killed off its host and left itself

no place to go, being replaced by a less deadly version.

The results of the Black Death

Along with an obsession with death that worked its way into European culture for generations to come, one can see the long term effects of the Black Death following three lines of development: a higher standard of living for those who survived, problems for nobles and clergy who were land owners, and revolts by peasants and urban workers. First of all, the Black Death had raised the standard of living of many survivors who inherited estates from the plague's victims. One sign of this was that peasant families, who, before the plague, were so poor that they sat at the dinner table on a common bench and ate from a common plate, now had individual stools and plates. This higher standard of living would lead to a more even wealth distribution and the recovery of the economy after 1450.Popular uprisings

Typically, war, plague, high taxes, or a combination of these would spark a sudden uprising. At first it would take the authorities by surprise, and they would either be killed or flee to the safety of the local towns or castles. In the case of peasant revolts, the unexpected success of an uprising would encourage other peasants to join and vent their frustrations on their own lords with incredible ferocity and cruelty. The rebellion would sweep through the countryside like wildfire, destroying any opposition in its path. However, the sudden nature of such outbursts also carried the seeds of their destruction, because they had very little, if any, organization or planning. Eventually, the authorities would gather their forces and crush the rebellion, since the rebels were poorly armed and trained compared to the professional warriors facing them. The aftermath would often see massacres and executions as retribution against the rebels and to discourage any further uprisings.

In the cities, workers tried to form their own protective organizations to win higher wages and better working conditions. This alarmed the guilds, which outlawed such organizations. That in turn enraged the workers who resorted to violence. The first such revolts occurred even before the Black Death hit Europe. The plague and its results merely intensified an already existing crisis.

The most serious of these, that of poor laborers known as the Ciompi, took place in Florence (1378) and followed a course similar to other popular revolts of the time: initial success (which in this case lasted four years), eventual victory for the authorities, and severe reprisals which only added to existing bitterness. The savagery of such revolts and the atmosphere of fear and hatred they created led the ruling classes in the cities to support princes and tyrants who could establish law and order. In Flanders, the dukes of Burgundy also established law and order under their strong autocratic rule. The greater security plus the collection of power and wealth in the hands of these rulers would be important factors supporting the cultural flowering of the Renaissance

Two revolts typified peasant uprisings, one in France and one in England. The Jacquerie, named after the popular name for French peasants, broke out in 1358, ten years after the Black and in the midst of the Hundred Years War with its destruction, high taxes, and forced labor to repair fortifications. On May 28, about 100 peasants in the village of St. Leu assaulted the nearest manor house and massacred the lord and his family. From there, the revolt spread quickly across the countryside with the usual atrocities and a reported 160 castles burned. Many towns, either out of sympathy or fear of the peasants, opened their gates to them.

The turning point came when some nobles returning from crusade in Eastern Europe came across and defeated some peasants at the town of Meaux. This encouraged them to organize and gather their forces against the main peasant force. The nobles then lured the peasant leader, Guillaume Cale, into a parley and murdered him. Deprived of their leader, the peasants were easy prey in the battle that followed. Hundreds were burned in a local monastery, and thousands more were hanged in their doorways as a warning against future revolts. Less than a month after the start of the revolt, it was over, although the fear and bitterness it bred lived on.

The Wat Tyler rebellion broke out in England in 1381. The immediate causes were much the same as those of the Jacquerie: high war taxes, a recent outbreak of plague, and a resulting agricultural crisis. The course of events was also similar. The rebels advanced all the way to London, looting and pillaging as they came. They even managed to seize and murder several of the king's officials. However, a daring ride in front of the rebels by the boy king, Richard II, who offered them concessions and supposedly his leadership in the revolt, settled them down. A parley was then arranged with the peasants' leader, Wat Tyler, which ended in his murder. This demoralized the peasants and allowed the nobles to defeat them and restore order in England much as the French nobles had in France. However, despite their ultimate defeats, the popular revolts of the day had two important results. First, they damaged the nobles' military reputations and power and paved the way for the emergence of kings and the modern nation state. Secondly, workers' and peasants' wages did rise, also leading to a more even distribution of wealth.

Decline of the Church and nobles

The Black Death also created problems for the nobles and clergy in

two main ways. First, the huge population loss in the cities'

caused a virtual collapse of the urban grain markets, a major source of

income for noble and church landlords with surplus grain to sell.

This especially hurt the nobles and clergy, whose incomes were still

based on land and who relied on selling surplus grain in the towns for

badly needed cash. There were two main strategies for making up

for this lost income.

Both nobles and clergy resorted to selling freedom to their

serfs. This raised some quick cash, but it also deprived them of

future revenues, which contributed to their decline and the

corresponding rise of kings and nation states. At the same time,

the serfs were now transformed into a free peasantry with more

incentive to work harder since they were working more for

themselves. This also helped lead to a more even distribution of

wealth which contributed to a revival of agriculture, towns, and trade,

especially after 1450 when the climate seems to have improved.

But with the guilds and nobles weakened by the turmoil of the last 150

years, a new broader consumer market evolved, but one where the average

person had less money to spend than the average noble beforehand would

have had. Since these people could not afford the guilds'

expensive goods and the guilds refused to adapt to this market, rich

merchants established cottage industries and sold their goods outside

of the guilds' jurisdiction. The profits they made and the

absence of the guilds' restrictive regulations helped these merchants

establish a new economic system, capitalism, which would replace the

guild system and lead the way into the modern world.

The Church had several other fund raising options in addition to

selling serfs their freedom: selling church offices (simony), letting

one man buy several offices at the same time, charging fees for all

sorts of church services, and selling indulgences to buy time out of

Purgatory after one died. These practices plus the Church's

inability to cope with the crisis of the Black Death led to growing

public discontent. As a result, the Church would experience

serious challenges to its authority in the Later Middle Ages.