Revival of the WestRevival of the West c.1000-1500 C.E.

High & Later Middle AgesUnit 10: The High and Later Middle Ages in Europe

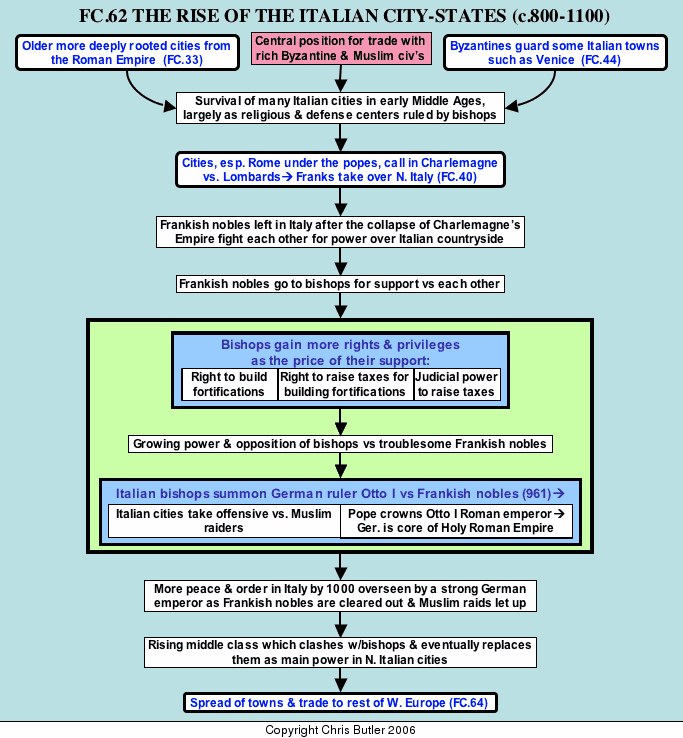

FC62Urban revival in Italy (c.800-1200)

The first stirrings of revival from anarchy in Western Europe took place in Italy. There were three reasons for this. First of all, the Roman cities were older and more deeply rooted than cities in Northern Europe. Second, their position in the middle of the Mediterranean attracted trade from the richer Byzantine and Muslim civilizations in the East. Finally, the Byzantine Empire, which ruled parts of Italy, protected its towns there from at least some of the chaos of the times. Italian towns were much reduced in size from the days of the Roman Empire, but they still functioned as religious centers ruled by bishops as well as centers of defense.

In the eighth century, the popes had summoned the Frankish rulers, Pepin the Short and Charlemagne to Italy to defend them against the Lombards. Especially as a result of Charlemagne's campaigns, the northern half of Italy came under Frankish rule. After Charlemagne's death in 814, law and order collapsed with the central government, but the Frankish nobles left behind by Charlemagne remained as the power in the countryside while the bishops ruled the cities.

The turmoil following Charlemagne's death attracted waves of Muslim raids These raids reached their peak in the ninth and tenth centuries, and, at one point, the Muslims even controlled part of Rome. Eventually, they were driven out, leaving the Frankish nobles in the countryside to fight one another for control of Northern Italy. Holding the balance of power in these struggles were the bishops in the towns. In order to enlist the bishops' aid the Frankish nobles promised various rights to them. Typically, the first of these rights was to build their own fortifications. Since such projects were expensive, the Franks gave the bishops the right to collect taxes. And along with that would come certain judicial rights that also brought in court fees. Over time, the bishops' power and their desire to break free from the nobles steadily grew.

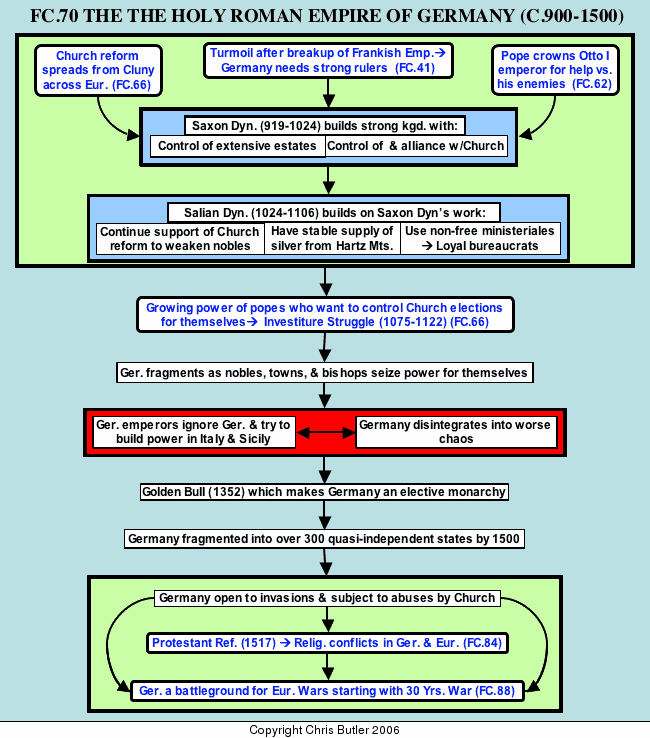

Luckily for the bishops, a strong German state with interests in Italy was emerging under Otto I. At the pope's request, Otto came down and crushed the power of the nobles and left the bishops in the cities as his agents of control in Northern Italy. This resulted in two things. For one thing, the pope rewarded Otto in 961 with the Roman imperial title that Charlemagne had been given 160 years before. For the next 850 years, the aura of the imperial title would influence German rulers' policy and be the cause of ruin for Germany. However, at this time, a strong Germany, or Holy Roman Empire as it came to be called, was useful for protecting the peace in Italy. Second, the Italian cities, now freed from the nobles, started to take the offensive against the Muslim raiders. By 1200, Italian navies and merchants would be powerful enough to dominate the Mediterranean, help the Crusaders conquer and maintain their states in Syria and Palestine, and even conquer Constantinople in 1204.

Together, these factors brought peace and security from the Muslims and Frankish nobles, which led to the revival of towns and trade. At first, this benefited the bishops ruling the cities, since it brought in more taxes from trade. But it also meant the rise of a middle class of artisans and merchants in each city who were increasingly dissatisfied with living under the rule of the bishops. Eventually, they rose up against the bishops and overthrew them, establishing independent town governments known as communes. As nobles moved into the towns where many of them took up trade and merchants seized more and more political power, the distinction between nobles and middle class became somewhat blurred. What emerged in Italy was a new nobility known as magnates (literally "great ones") that was a fusion of these two groups.

It is important to note that while we talk about Italy as a country, it still existed as a patchwork of different and competing states. Northern Italy, in particular, was made up of a large number of independent city-states, the most important being Venice (a former Byzantine city), Genoa, Pisa, and, later on, Milan and Florence. It was these cities that led the way for Western Europe to emerge from the Early Middle Ages. Their example and wealth would help spark a similar revival of towns north of the Alps. However, as we shall see, the political development of Northern Europe would be quite different from that of Italy, giving rise to the emergence of what would be our modern nation states.

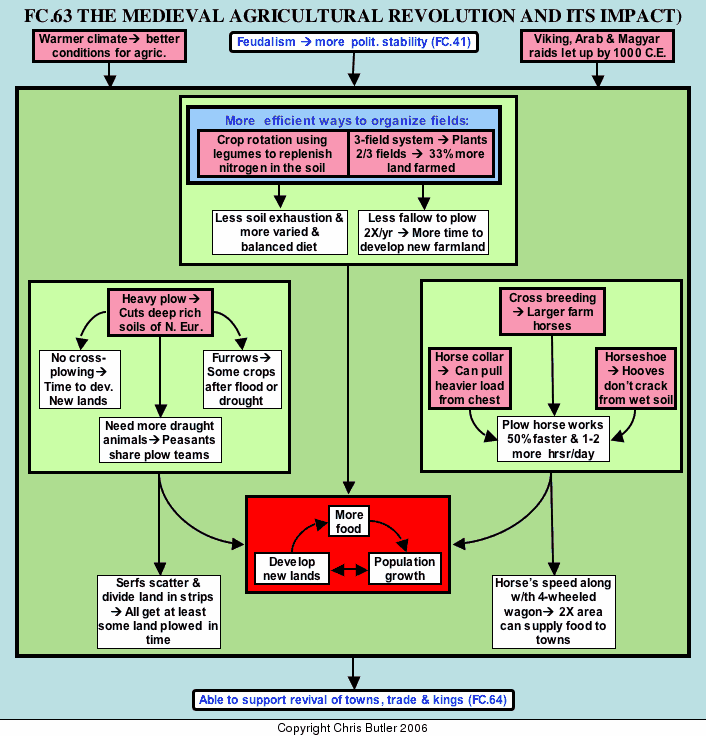

FC63The agricultural revolution in medieval Europe

Until this century, the vast majority of people spent their lives involved in one basic occupation: getting food, either through hunting and gathering, herding, or agriculture. When these people could produce a surplus, they were freed to do other things, which provided the basis for towns, cities, and civilization. Without the ability to produce surplus food, no civilization would be able to survive. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the first step in building a new civilization in Western Europe was developing ways for producing a surplus of food.

Europe (c.1000 C.E.)

Before discussing these new agricultural techniques, it is useful to look at the state of Medieval life and agriculture in the Early Middle Ages. The vast majority of peasants were serfs, bound to the soil and service of a lord who owed them protection in return for work in his fields. These serfs lived in villages, isolated pockets of farmland in the midst of a vast wilderness of forests, thickets, and marshes. Typically, a village would have several acres of cultivated fields, a wooden castle or manor house for the lord, a peasant village, a parish church, and a mill. A village might be equivalent to a manor, the economic unit given to support a noble. However, it could just as well be divided into several manors to support several nobles or be only one of several villages making up a large manor.

The village had to be self-sufficient because it was virtually cut off from the outside world. Roads were poor and brigands or local lords constantly threatened travel. Raids from neighboring nobles and such invaders as the Vikings, Magyars, and Moslems also kept most people huddled under the safety of their lord's castle walls. As a result, the flow of trade and commerce was reduced to a fraction of what it had been during the Pax Romana. Compared to the thriving Byzantine and Islamic cultures to the south and east, Western Europe was a fragile outpost on the western fringe of civilization.

Europe’s agriculture reflected this low level of culture. The plow used then was still the scratch plow that worked fine in the thin dry soils of the Mediterranean, but was not very suitable for the wetter, deeper soils of Northern Europe. Such a plow might be reinforced with iron, or it might be nothing more than a curved digging stick. The main source of power for pulling the plow was the ox hooked up by a yoke harness that pulled at the neck. Although slow, the ox was more than some peasants could afford. As a result, they had to pull their own plows or dig with spades (known as delving). Finally, the peasants used the two-field system, where one field lay fallow to reclaim the soil's nutrients while the other field was being cultivated. This left only fifty percent of the farmland for use in any given year. As a result, crop yields were very low. In the Roman Empire, for every bushel of seed grain planted, four bushels would be harvested. In the Early Middle Ages with the poor techniques being used, this ratio dropped to one and a half or two to one. In other words, a full half or more of a peasant's harvest had to be saved as seed grain for next year's planting. In years of famine, this led to serious difficulties. Given these limits, it should come as no surprise that population remained low and grew at a very slow rate, if at all.

One has to be very careful when generalizing about what techniques were used where. This is because we have little evidence to go on, especially concerning the peasants, whose lives were of little concern to the monks writing religious histories. Also, the poor communications between manors meant that widely different techniques and tools might be used in a fairly local area. However, it does seem likely that the light scratch plow, oxen, yoke harness, and two-field system were in general use in Western Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Then came some changes that would lay the foundations for more advanced civilization.

First stirrings of revival

It is impossible to say when population first started expanding in Western Europe, although we can make some educated guesses. For one thing, the climate seems to have turned warmer in the 800's. We base this on tree ring evidence and the fact that the Vikings could sail in northern latitudes unobstructed by ice. The warmer climate meant longer growing seasons, better harvests, and thus a healthier and growing population. Major plagues that had hit intermittently since the later Roman Empire also ceased after 743 C.E. This might be partly a result of the better-fed population having more resistance to disease. Finally, a certain amount of political stability had returned to Western Europe by 1000 C.E. The feudal system, whatever its faults, was providing at least a minimal amount of security to Europe. Along with this, the invasions of Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims were letting up by this date. The increased stability created by all these factors helped provide the conditions needed for population growth and economic revival. This brings us to new farming techniques that would greatly expand food supplies and lead to the rise of towns.

An agricultural revolution

The first of these techniques was the three-field system. Originally, the spread of civilization to Northern Europe brought with it the two-field system. This was well suited to the climate of the Mediterranean with its hot dry summers and one growing season in the cooler, wetter winters. The more temperate climate of Northern Europe allowed growing seasons in both summer and winter. However, planting two crops a year would exhaust the soil if peasants used the old two-field system. As a result, peasants divided their farmland into three fields, one for winter crops, one for summer crops, and one to remain fallow. The use of the fields was rotated each year. A second part of the system, in order to prevent soil exhaustion, was to use different crops that took different nutrients from the soil. The winter crop typically would consist of winter wheat or rye, and the spring crop would be either spring wheat or legumes (beans or peas). The greater variety of crops provided people with a more balanced diet. Also an advantage of legumes is that they take nitrogen out of the air rather than the soil, and when buried, actually replenish the soil with nitrogen. (The Romans referred to this as "green manuring".) The following charts show how the two systems work.

| TWO-FIELD SYSTEM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Field 1 | Field 2 | |

| Year I | Winter crop | Fallow |

| Year II | Fallow | Winter crop |

| Year III | Winter crop | Fallow |

| THREE-FIELD SYSTEM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Field 1 | Field 2 | Field 3 | |

| Year I | Winter crop | Summer crop | Fallow |

| Year II | Fallow | Winter crop | Summer |

| Year III | Summer crop | Fallow | Winter crop |

| Year IV | Winter crop | Summer crop | Fallow |

Consider what the changeover from the two-field system would have meant to a peasant village farming 60 acres. In the old system only 30 acres would be planted each year. In the new three-field system 40 acres would be planted, an increase of 33%. Also, peasants would plow the fallow land twice to keep weeds down. In the two field system this mean plowing all 60 acres once plus the 30 fallow acres again, 90 acres of plowing in all. The three-field system, involved plowing all 60 acres plus only 20 acres of fallow again, a total of only 80 acres of plowing. Thus while producing 33% more food, the peasants were plowing considerably less, especially considering what hard work plowing was back then. The extra time saved could be used for clearing new farmland from the surrounding wilderness, which, of course, meant even more food. Likewise, the extra food meant more people from population growth, who would also clear new lands to produce more food, and so on. Eventually, enough new land would be cleared and surplus food produced to support population in towns.

Another major development in farming was the heavy plow that could cut through the deep, wet, and heavy soils of Northern Europe much better than the light scratch plow. It had three basic parts: the coulter or heavy knife that cut through the soil vertically, the plowshare that cut through the soil horizontally, and the mouldboard, which turned the soil to one side. Some models had two wheels that acted as a fulcrum to keep the plow from getting stuck. There were two advantages to this kind of plow. First, it cut the soil so violently that there was no need for cross plowing as there was with the scratch plow. This saved time, which could be used for, among other things, clearing more land and producing more food. Second, the heavy plow created furrows, little ridges and valleys in each plowed row. In times of drought, water would drain into the valleys and ensure some crops would survive. In times of heavy rains, the crops on top of the ridges would not get flooded out. As a result, peasants could usually look forward to at least some crops to harvest even in bad years. The furrows the heavy plow created also meant that the rich alluvial bottomlands by rivers could be farmed without their frequent floods doing too much damage. As with the three-field system and crop rotation, the heavy plow also fed into the feedback cycle of more food, population growth, etc.

The heavy plow had an impact on peasant society and land holding patterns. Being heavy, it required as many as eight oxen to pull it compared to two oxen on the scratch plow. Since few peasants could afford their own teams, they would combine their ox teams and hook them to one plow. Occasionally, disputes might arise as to whose land would be plowed first, especially if the weather had been bad and it was doubtful that all the fields could get plowed in time for a good crop. As a result, peasants split their lands into long strips and interspersed them among other peasants' and the lord's strips. Some peasants might have 50 or 60 strips spread out over the manor. The advantage of this was twofold. First of all, it ensured that everyone got at least some land plowed. Second, the long strips of land meant that the plow team did not have to turn as much, one of the most difficult aspects of plowing, especially with four rows of oxen to increase the turning radius. The heavy plow also created a more cooperative peasant society and caused small hamlets to combine into larger villages in order to share ox teams.

The last major development in farming was a new source of power, the plow horse. Several factors allowed the use of the horse in Western Europe. The invention of the horseshoe (c.900 C.E.) prevented the hooves of the horse from cracking in the cold wet soil. The horse collar let the horse pull from the chest rather than the neck. This increased the horse's pulling power from about 1000 lbs. (with the yoke harness) to as much as 5000 lbs with the horse collar. Finally, cross breeding to make larger warhorses also provided the peasants with larger plow horses. Although it could not pull any more than an ox, the horse did have two advantages. It could pull up to fifty percent faster than the ox, and it could work one to two hours longer per day. The one drawback was that the horse ate a lot. Overall, despite eating more, the plow horse could increase farm production as much as 30 percent for those peasants who could afford horses. As with the three field system and heavy plow, this led into the feedback cycle of producing more food, population growth, and developing new lands for even more food production, etc.

There were some interesting side effects of the use of the horse. Being fifty percent faster than oxen, horses could bring food into a town from outlying villages fifty percent farther away without taking any more time than before with an ox team. Increasing the radius of the surrounding farmland supplying a town by fifty percent more than doubled the area of farmland and amount of agricultural produce available to support that town, and, subsequently, the potential size of the town itself. In addition, the replacement of the two-wheeled cart with the four-wheeled wagon with a hinged post for greater maneuverability increased the amount of grain a peasant could bring into town.

We should keep in mind the limits to medieval agriculture. While a yield to seed ratio of four to one was good back then, farmers today expect at least ten times that. What this means is that for centuries it took ten farmers to create enough surplus to support one townsman. Still, along with the greater stability brought by feudalism, the increased food production brought on by the agricultural revolution of the Middle Ages was essential for the revival of towns, without which our own civilization would not have evolved.

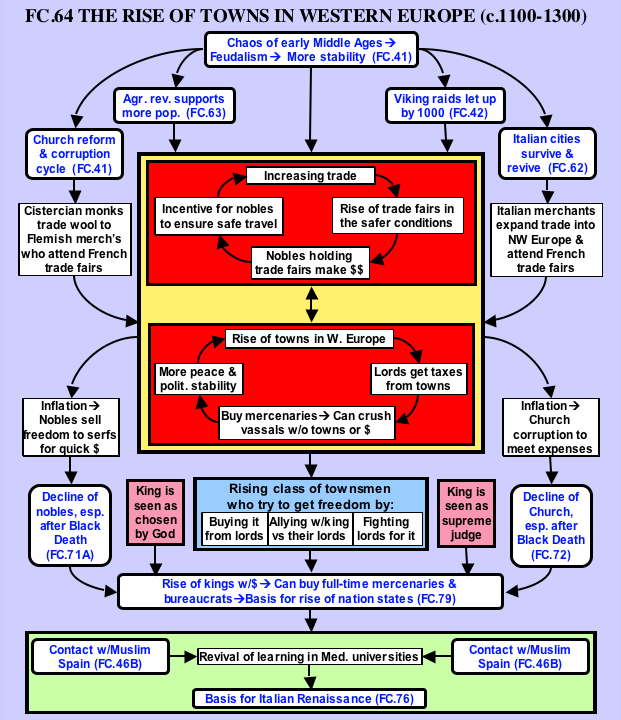

FC64The rise of towns in Western Europe (c.1000-1300)

From trade fairs to towns

In the twelfth century, towns and trade in Western Europe, which had long been in decay since the end of the Roman Empire, saw a renewed outburst of energy. A combination of four factors would lead to this. First, there were the old Roman cities in Italy that had evolved from centers of defense into thriving towns with a strong middle class primarily concerned with trade and manufacture.

Second, another area, Flanders (roughly equivalent to modern Belgium), soon saw the development of towns and trade also. Crucial to this was the wool industry started by a new monastic order, the Cistercians. These monks were part of the ongoing cycle of Church corruption and reform that usually started with the monasteries. To protect their spiritual purity from the corruption of the outside world, they would found their houses "far from the haunts of men." Oftentimes, this was on hilly rocky ground that was often unsuitable for farming. Other uses were found for it, in particular raising sheep. The Cistercians were well organized and very good at raising sheep and wool, which they traded to Flemish merchants, who started a wool industry and towns.

However, the Flemish had a problem that limited the scope of their operations: slow weaving on the old hand loom. Luckily, an improved mechanical loom came up from Muslim Spain sometime in the eleventh century. This device, possibly originating in China, eliminated hand weaving the weft thread in and out between each individual warp thread. Instead, foot pedals attached to every other warp thread would raise those threads and speed up the process of weaving in one direction. Another foot pedal would raise the other warp threads for the weft coming back. This increased wool production, but the traditional method of spinning thread with the drop could not keep up with the pace of weaving. Not until the thirteenth century, thanks largely to the crusades and increased contact with the East, was the spinning wheel introduced, which quickly pulled and spun wool through a spindle and wound it on a bobbin. Woolen production jumped by a factor of ten times and Flemish woolens became the basis of a thriving urban culture in northern Europe.

Indeed, Flemish wool was a highly valued commodity, reputedly being as smooth as silk. The tendrils of Flemish trade stretched far and wide, but especially across the Channel to buy rough English wool for weaving into fine Flemish product. The close economic ties this bred between England and Flanders, then a French vassal, would help lead to the Hundred Years War. The influence of Flemish woolens also reached southward to Italy and beyond, touching off trade at intervening points in France where towns next revived.

The emerging feudal order helped make possible two other factors vital to the rise of towns and trade. One was the agricultural revolution that could support town populations. The other was the end of Viking and Arab raids that made the roads safer for trade. These four factors helped create more political stability, which encouraged merchants to take to the roads once again. In the middle of the old Roman trade routes linking Italy and Flanders was the French county of Champagne, whose counts were shrewd enough to take advantage of this trade by sponsoring six annual trade fairs held in four rotating locations. Rather than robbing these merchants, the counts charged them for the use of booths, local justice, lodging, food, and protection. Among those attending these fairs and providing the counts with revenues were wealthy merchants from Italy and Flanders.

The excitement these fairs generated was infectious. So were the profits. Some jealous nobles attacked and robbed merchants traveling to the fairs. Others, being more far-sighted, worked to ensure safer travel so they could start their own fairs and make their own profits. With each new fair came greater incentive to stifle troublesome local nobles and increase political order. This in turn stimulated more trade fairs, more profits, more law and order, and so on.

Eventually fairs and trade became so common that merchants started settling down in permanent towns. Generally, such settlements were on well-traveled routes that could attract the trade of passing merchants. They also were under the protective walls of a lord's castle, an abbot's monastery, or a bishop's settlement. Many towns were brand new settlements, but others were outgrowths of already established communities. Even today, many European towns have a castle in or near them, evidence of their medieval beginning.

The impact of towns

More stable conditions had helped produce the rise of towns. The towns in turn helped create even more peaceful conditions with far reaching effects. For one thing, towns generated taxes in the form of money, a new more fluid kind of wealth vastly superior to land as the primary form of wealth. Previously, almost any noble with a castle and a stockpile of food could defy his lord by going under siege, since feudal armies were notoriously unstable and prone to breaking up after their terms of service (usually forty days) were up. However, the more powerful lords that could attract settlers for towns now had money from taxes. With that money, they could buy mercenaries, usually landless knights, who would fight as long as the lord could pay them. Such armies were more stable and allowed their owners to crush the power of their rebellious vassals and establish more law and order. The increased order would encourage more towns which would generate more taxes for the king and upper nobles, who could impose even more law and order, and so on. This would also feed back into the ongoing cycle encouraging trade fairs. All this led to two things: a rising class of townsmen and a money based economy, both of which would help lead to the rise of kings.

Money created another problem especially hurting the nobles and Church: inflation. At first, when towns were just getting started and there was little money in circulation, the fixed rent set by the original town charter seemed like a good deal. However, as more money came into circulation, prices rose, and the buying power of the fixed rents declined. This especially hurt the nobles and the Church. The nobles often took the short term expedient of selling freedom to their towns and serfs for one lump sum. This gave them some immediate cash, but wrecked much of their power, leading to the decline and eventual end of the feudal order.

The Church, with its wealth mostly in land and fixed rents, also suffered. It did have other options for raising money, namely selling church offices and indulgences (reprieves from punishment in Purgatory before being admitted into Heaven). Such practices were subject to abuse and led to popular discontent that cut into the Church's power and prestige. Eventually, that would lead to the Protestant Reformation, which would destroy the Catholic Church's religious dominance in Western Europe.

As far as townsmen were concerned, nobles and churchmen first saw them as an asset providing them with taxes and militia. However, as the class of townsmen grew, so did tensions with their overlords. For one thing, townsmen (or burghers, from burg, the German word meaning town) felt increasingly stifled under a lord's rule. The two classes had very different values, the burghers being concerned with trade and commerce and their overlords being concerned with power and fighting. Therefore, one by one, towns started trying to gain their freedom. Some towns bought it with one big payment to the lord or fought for it, sometimes in long protracted struggles. For example, the town of Tours in France fought twelve wars before it finally won its independence.

Another tactic was to appeal to the king for support, since kings and townsmen saw each other as valuable allies against the nobles and Church in between. Eventually, the towns managed to break free and form communes (urban republics) like their counterparts in Italy. Oftentimes confirming the town’s independent status would be a charter that would detail the specific duties and liberties the town and lord owed each other. Also, as serfs and towns bought their freedom, they came more closely under the king's authority, supplying him with taxes and loans.

Two other factors unique to the king gave him an edge over other nobles. One was his religious position as God's appointed ruler, which was symbolized by a churchman anointing him with oil in the same manner as Biblical rulers. The second factor was his position as the supreme judge of the land. When the kings were weak in the Early Middle Ages, this did them little good. However, as they rose in power, they could exercise their judicial powers more effectively, which in turn would give them more political power and so on.

All these factors, the rise of a money economy, the growing class of townsmen, and the kings' judicial and religious status gradually led to the decline of the medieval Church and nobles and the corresponding rise of kings with money that could buy them two things. One was stable full time mercenary armies that would fight for as long as they were paid. The other was a bureaucracy drawn increasingly from the middle class. These new royal bureaucrats had several advantages over feudal vassals. For one thing, they were more loyal, being the king's natural allies against the nobles. Also, they were more efficient since they were generally literate and could keep records. Finally, they were easier to control because they were totally dependant on the king for their status. Also, they were paid with money, so the king could just cut their pay if they got out of line. This contrasted greatly with the land based economy of the Early Middle Ages when the king had to physically drive rebellious vassals from their lands. Although the rise of kings and national monarchies would be a centuries long process, it was the rise of towns starting in the twelfth century that set that process in motion and laid the foundations of the modern world.

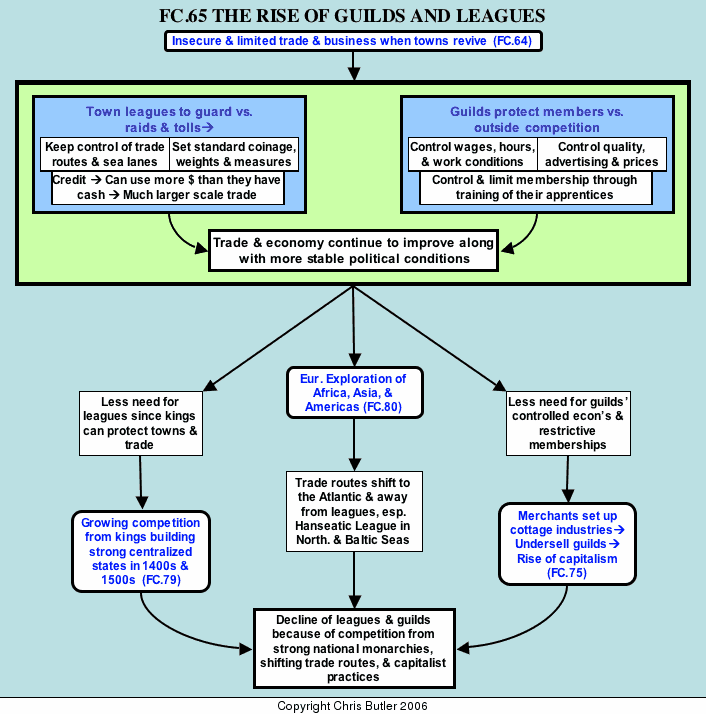

FC65Leagues & Guilds in Western Europe

The years when towns and trade were first reviving in Western Europe were precarious ones for the emerging middle class of merchants and artisans. Costly tolls levied by local nobles hampered trade when times were peaceful, while more turbulent times could see each of those nobles cutting off trade and marauding merchants on the road. Different weights, measures, and standards of coinage complicated transactions between merchants of neighboring towns. Famine could drive prices up dramatically, thus cutting down the flow of trade and causing turmoil among the workers who wanted higher wages to keep up with rising prices. Given such a dangerous world for the medieval merchants and artisans, it should come as no surprise that they formed associations, leagues and guilds, to protect and promote trade. These were not examples of free enterprise, however. Their purpose was to exclude outside competition from their markets since the evolving market economy was seen as too fragile to sustain much competition.

Leagues

In northern Europe, various towns would band together in leagues to establish collective security. The most important of these leagues was the Hanseatic League*, which was centered on the city of Lubeck in the southwest corner of the Baltic Sea. At the height of its power (c.1350 C.E.) the League contained over seventy German cities throughout the Baltic and North Seas. It kept an effective monopoly on the trade in this area by keeping out Russian, Scandinavian, and English competition. When pirates, local lords, or even kings threatened their trade or freedom, the League's forces could successfully defend their interests. The king of Denmark found this out to his dismay in 1370 when he tried to encroach on the League's territory and was driven back. The Hanseatic League dominated the trade of the Baltic and North Seas in the north much as the Italian cities dominated the Mediterranean trade in the south.

Besides common military action, the Hanseatic League carried out other measures to protect and promote trade. For one thing, it established common weights, measures and coinage throughout its member cities. This cut down on the time-consuming hassles of having to convert from one weight and measurement system to another each time a new business transaction took place. Today we are in the final stages of this standardization process, as the metric system is being pushed for worldwide use.

The Hanseatic League's success was also based on more advanced business techniques, in particular the use of credit. With a cash economy, a merchant could only buy as many goods as he had the cash on hand to pay with, which severely limited the scope of his activities. With credit that merchant could borrow more money than he actually had and use it to buy goods that he could sell for a larger profit than with a cash economy. This was because he was borrowing, buying, and reselling on a much larger scale (even after repaying the loan) than he ever could if he were dealing strictly with cash. As the merchant’s credit rating improved, he could borrow ever-larger sums of money, oftentimes in several places at a time through the use of his agents, which vastly expanded the scope of his activities, his profits, and his credit rating. Buying in larger volume also allowed him to sell each unit of goods more cheaply and thus undersell other merchants not dealing in credit. In such a way, the Hanseatic League established a virtual monopoly on trade in the Baltic and North Seas.

The political expansion of the German people also helped the German cities of the Hanseatic League. At this time, German peasants and the crusading order of the Teutonic Knights were expanding into the interior of Eastern Europe against the Slavic peoples there. Meanwhile, the German cities founded colonies in their wake, thus increasing their economic power over the Baltic Sea and further restricting competition there.

Although the Hanseatic League was the most important of the medieval town leagues, it was by no means the only one. There were several leagues of towns along the Rhine whose main concerns were to stop the raids of local nobles on trade and to curb the tolls those nobles imposed on goods passing through their territory. The most famous of these leagues, the Swabian League, had over eighty member cities at its height (late 1300's) and was strong enough to challenge the dukes of Austria and Bavaria. In Flanders, there was a league of twenty-two towns whose purpose was to buy raw wool from England. Another league of seventeen towns in Champagne County, France regulated marketing practices at trade fairs. Whatever their functions, the cumulative effect of leagues was to improve the trade and economy of Western Europe. And that in turn contributed to the rise of kings and more stability.

Guilds

served much the same function on a local level as leagues did on a wider geographic level: protecting their members from the dangers of outside world, whether they were marauding nobles and bandits, economic ruin, or outside competition. Originally each town would have one guild encompassing all crafts. However, as the towns grew, the guilds evolved into various specialized guilds: merchant, goldsmith, armorer, tailor, bargemen, etc. By 1200 C.E., Venice had fifty-eight guilds, Genoa thirty-three, Florence twenty-one, Cologne twenty-six, and Paris one hundred. The purpose of each guild was to exclude outsiders from practicing that guild's craft or trade within the city walls. Although this virtually eliminated free enterprise, it did provide a stable atmosphere in which the newly evolving crafts and trades could develop and survive.Guilds went much farther than excluding outside competition from within their walls. In fact they controlled just about every aspect of the town's economy, in particular wages, prices, quality of goods, and guild membership. For example, an armorer would buy the materials he needed through the guild at a set price, not on his own for whatever price was cheapest. His workers worked for the number of hours and wages set by the guild. His armor had to be of certain quality meeting the guild's specifications. He could not advertise beyond setting one example of his work in his window. The guild also determined the price he could charge so he would not get an advantage over other members of the guild. Set prices also reflected the Church's displeasure with profits.

Training for and admission into the guild were also strictly regulated. Apprenticeship was almost always restricted to sons or nephews of guild masters, something that caused anger among the common laborers. Typically, a master craftsman would send his son to another craftsman for apprenticeship at the age of ten to twelve years. The boy would live in the master's home, work in his shop, and learn the craft in an apprenticeship lasting from three to fifteen years. At the end of his training, the apprentice would usually get a gift of money from the master to help him start his own business. He then became a journeyman who worked as a day laborer for different masters until he could save enough money to start his own shop. When he was ready, the journeyman would be examined by the guild masters for his technical ability, oftentimes having to produce a masterpiece to show his proficiency at the craft. If he passed the exam, and there was room in the guild, he became a master who shared in the limited, but fairly stable market established by the guild for its members.

The guild was more than a business association. It was also a social and political organization that looked after the welfare of its members. It provided justice by settling disputes between its members. It supervised the morals of its members in such matters as public fighting, drunkenness, and a dress code. It provided insurance against fire, flood, theft, prison, and old age (for those few who survived that long). It paid for members' funerals and for masses and prayers to free their souls from Purgatory. The guilds would also build hospitals, almshouses, schools and orphanages for the many orphans in society back then.

The guild was also a source of pride for its members. Each guild had its own guildhall where meetings and social functions were held. On the day celebrating its patron saint, a guild would put on parades and religious plays. Guilds would also dedicate to the town cathedral stained glass windows depicting biblical scenes that were also concerned with that guild's particular craft.

Guilds, like leagues, caused Europe's economy and trade to improve, which made possible the rise of kings and more stable conditions. However, those very kings who profited from guilds and leagues were largely the cause of their decline in the 1400's. For one thing, the stable conditions protected by the kings made the guilds’ protective restrictions unnecessary. In spite of this, the guild masters who ran the towns restricted membership even more than before while maintaining strict price and quality controls on their goods. Earlier, such practices had been good since they had protected a fragile trade vulnerable to the harsh conditions of the time. By the late 1400's, those same practices that had once protected the guilds now worked to destroy them. Restrictive membership and low wages, even in time of inflation, led to worker revolts in many cities. Even more devastating was the competition from outside of town. Rich merchants started cottage industries where they moved production outside the city walls (and the guilds' jurisdiction). Here they could pay individual peasants lower wages to produce wool and undersell the guilds which were still locked into their controlled wage and price structure. As a result, guilds went into decline.

The rise of strongly centralized states in the Later Middle Ages also hurt leagues, because the kings now protected trade and also saw the leagues as rivals for political power. At the same time, stability and trade fostered by the rise of kings sent explorers looking for new markets. The discovery of new trade routes to America and around Africa shifted trade away from the Baltic and North Seas, thus hurting the German leagues.

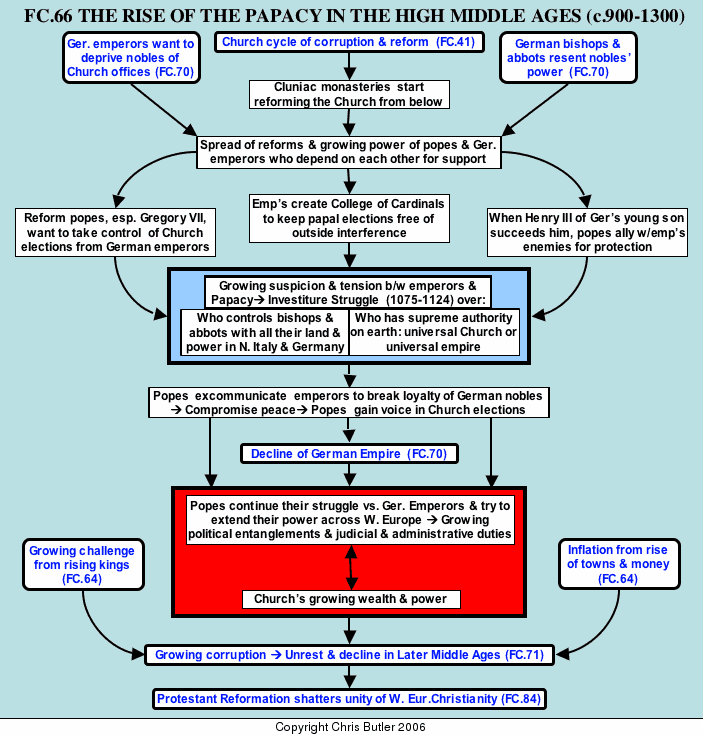

FC66Rise of the medieval Papacy (c.900-1300)

Introduction: the plight of the Church in the Early Middle Ages

Few stories better illustrate the problems of the medieval Catholic Church than the story of Pope Formosus. When this pope died in 856, his troubles were far from over. A personal enemy became the new pope and had Formosus' body dug up and put on trial. To no one's surprise, the late Formosus was convicted of illegally seizing the papal throne. His body was stripped of its priestly vestments, the fingers on his right hand (used for giving the benediction) were cut off, and his body was thrown into the Tiber River. Not surprisingly, the rest of the Church, ranging from bishops, archbishops, and abbots down to the lowliest monks and parish priests, was also seething with corruption.

The Church's wealth, some 20-30% of the land in Western Europe, was a big part of the problem. With little money in circulation at this time, land was the main source of wealth and power, making the Church the object of the political ambitions of nobles throughout Europe. Naturally, such nobles, who were warriors by trade, usually ignored and even trampled over the religious interests of the Church.

The zeal for reform (910-1073)

Even in such troubled times, the Church's ongoing cycle of corruption and reform meant there were always men of religious conviction determined to set the Church back on its spiritual path. As so often happened, reform started in the monasteries, in this case in the monastic house founded at Cluny, France in 910 C.E. The monks of Cluny placed themselves directly under the pope's power and out of the reach of any local lords. That meant virtual independence from any outside authority, since the popes were too weak to exert any authority from so far away. Technically, they were Benedictines and there was no separate order of Cluniac monks, but their agenda of reforms became so widely adopted that they have been referred to as Cluniacs ever since. Over the next 150 years, Cluniac reforms spread to hundreds of monasteries across Western Europe.

The zeal for reform was also strong in Germany, especially among the upper clergy and the emperors. The emperors saw church reform as a way to weaken the power of the nobles trying to control church lands and elections. By the same token, devout bishops and abbots looked to the German emperors for protections from ambitious nobles. As a result, both German emperors and German clergy supported the growing reform movement. Emperors put reformers into church offices throughout Germany. Such men were generally loyal to the emperor since they owed their positions to him and saw him as the main defender of reform.

The emperor, Henry III, even appointed four reform popes. One of them, Leo IX, carried out numerous reforms against simony (selling church offices), clerical marriage, violence, and overall moral laxity among the clergy. He even felt strong enough to tangle with the patriarch in Constantinople, thus causing a schism (break) within the Church in 1054 that was never healed. Since that time, the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches have functioned as two separate Churches. Consequently, by the mid eleventh century, the popes were taken seriously as a real moral force in Western Europe. However, a storm was about to break that would destroy relations between Church and Empire.

The Investiture Struggle (1073-1122)

In 1056, the reform Church's main ally and guardian, Henry III, died leaving a child, Henry IV, as his successor. This deprived the Church of any effective imperial protection until the young emperor came of age. As a result, the popes had to seek new allies, and settled on the Normans in Southern Italy and the dukes of Tuscany in Northern Italy. Both of these were enemies of the German emperors, thus creating a tense situation between the popes and Henry IV when he came of age. One reform adding to the tension was the creation of the College of Cardinals whose job it was to meet in private to elect a new pope. Designed largely to keep the turbulent Roman mob out of papal elections, it also kept the German emperors out of direct participation, although they still could veto any choice the College of Cardinals made.

Another problem was the pope, Gregory VII, an ardent and stubborn reformer who agitated to replace imperial with papal control of Church elections. Growing suspicion and tension between pope and emperor finally erupted in the Investiture Struggle over who controls Church elections and invests (bestows) the bishops and abbots with the symbols of their power.

The stakes in this fight were high on both sides. Henry needed control of the bishops and abbots to maintain effective control of his empire. Pope Gregory felt the Church had to free itself from outside secular control if it were to fulfill its spiritual mission. There was also the larger question of who was the real head of the Christian world: the Universal Empire or the Universal Church. Although the Byzantine emperor in the east usually held sway over the patriarch in Constantinople, this question of supremacy, extending back through Charlemagne to the later Roman Empire, had never been resolved in Western Europe.

The Investiture struggle was a bitterly fought conflict on both sides. Pope and emperor stirred each other’s subordinates into revolt. The reform bishops, appointed up to this time by the emperor, generally supported him against the pope. Meanwhile, the pope stirred the German nobles into rebellion against Henry. When Henry and his bishops declared Gregory a false pope, Gregory excommunicated Henry. Excommunication could be a decisive weapon since it released a ruler's vassals from loyalty to him until he did penance to get accepted back into the Church. As a result, Henry did such penance by standing barefoot in the snow outside the pope's palace at Canossa.

However, the struggle was hardly over. Gregory was driven from Rome and died in exile in the Norman kingdom to the south, while Henry's reign ended with Germany torn by civil war and revolts. Finally, a compromise was reached where only clergy elected new bishops and abbots, but in the presence of an imperial representative who invested the new bishop or abbot with the symbols of his secular (worldly) power. Although the struggle between popes and emperors continued for centuries, the popes had won a major victory, signifying the Church's rising power and a corresponding period of decline for Germany.

The Papal monarchy at its height (1122-c.1300)

The papal victory in the Investiture Struggle and the higher status it brought the popes led to many more people turning to the Church to solve their problems, in particular legal ones. Canon (church) law and courts were generally seen as being more fair, lenient and efficient than their secular counterparts.

However, the more the Church's prestige grew, the more its courts were used, and the more its bureaucracy grew. As a result, the popes found themselves increasingly tied down with legal and bureaucratic matters, leaving less time for spiritual affairs. The popes of the 1200's generally had more background in (church) law than theology. By and large they were good popes, but also ones with an exalted view of the Church's position. The most powerful of these popes, Innocent III (1199-1215), even claimed that the clergy were the only true full members of the Church.

Unfortunately, growing power and wealth again diverted the Church from its spiritual mission, and led to growing corruption. Two other factors aggravated this problem. One was the rising power of kings, which triggered bitter struggles with the popes over power and jurisdiction. Popes often used questionable means in these fights, such as overuse of excommunication, declaring crusades against Christian enemies, and extracting forced loans from bankers by threatening to declare all debts to the bankers erased if the loans were not granted. A second problem was inflation, which arose from the rise of towns and a money economy. The Church, with its wealth based in land, constantly needed money and therefore engaged in several corrupt practices: simony, selling indulgences (to buy time out of Purgatory for one's sins), fees for any and all kinds of Church services, and multiple offices for the same men (who were always absent from at least one office).

All these factors combined to ruin the Church's reputation among the faithful and undermine its power and authority. Eventually, they would lead to the Protestant Reformation, shatter Christian unity in Western Europe for good, and help pave the way for the emergence of the modern world.

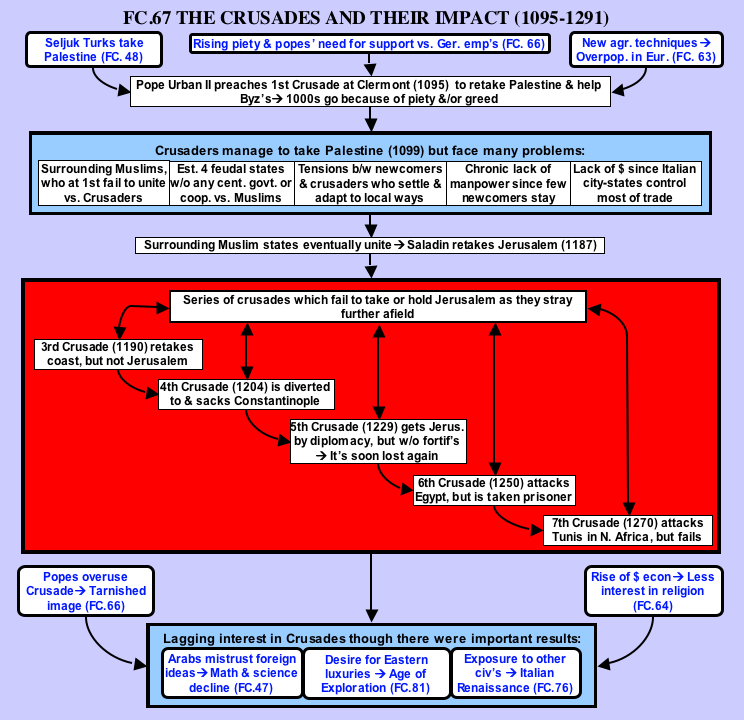

FC67The Crusades & their impact (1095-1291)

...But these were small matters compared to what happened at the temple of Solomon, a place where religious services are ordinarily chanted. What happened there? If I tell the truth, it will exceed your powers of belief. So let it suffice to say this much at least, that in the temple and portico of Solomon, men rode in blood up to their knees and bridle reins. Indeed, it was a just and splendid judgment of God, that this place should be filled with the blood of the unbelievers, when it had suffered so long from their blasphemies.— Foucher de Chartres

The First Crusade (1095-99)

The modern reader (both Christian and non-Christian) is justifiably shocked at how medieval Christians such as Foucher de Chartres exulted in the wholesale butchery that took place in Jerusalem, the holiest city of Christianity, to end the religious war known as the First Crusade. However, that description expresses quite well not just the rough edge of medieval Christian faith, but also the power and energy that, for nearly two centuries, drove Europeans to launch the Crusades in order to conquer and hold Palestine. There were several reasons for the Crusades happening when they did.

First of all, there was the expanding power of Western Europe in the eleventh century. More settled conditions plus better agricultural techniques helped trigger population expansion that created large numbers of landless younger sons of nobles. Adding to these pressures was a series of bad harvests providing an even greater incentive to find land elsewhere. While the Crusades were the most dramatic and publicized example of Europe's expanding frontiers, there was similar expansion by Spanish Christians in Spain, by the Normans in Southern Italy and Sicily, and by the Germans in Eastern Europe.

The most immediate reason centered on events in the Middle East. In the eleventh century, a new people, the Seljuk Turks, replaced the Arabs as the dominant power in the Islamic world, overrunning most of Asia Minor after crushing the Byzantine army at Manzikert (1071) and seizing Palestine from the Shiite Fatimids of Egypt. These conquests led to pleas to the West for help, both from Christian pilgrims to Palestine who suffered from mistreatment at the hands of the Turks and from the Byzantine emperor, Alexius I, who just wanted mercenaries with which he could reconquer Asia Minor. As an added enticement, Alexius held out the possibility of reuniting the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, which had been split since the schism of 1054.

The rising power of the Church at this time was another factor leading to the Crusades. This created a rising tide of piety in Western Europe that expressed itself in pilgrimages to Palestine before the Turks seized it, and adapted itself to a holy war (crusade) after the Turkish conquest. This rising tide of piety was part of a broader movement for Church reform led by the popes that had caused the Investiture Struggle with the German emperors over control of the election of Church officials. Both the reunification of the Catholic Church with Byzantium and the recovery of Jerusalem fit into the larger ambitions of Pope Urban II. If the pope could lead all of Christendom in a crusade to recover the Holy Land (Palestine), then his moral authority would far surpass that of the German Emperor. Therefore, in 1095, at the French town of Clermont, Pope Urban II preached the First Crusade (from the Latin word, crux, for cross) to liberate the Holy Land from the Turks. Apparently his speech struck a nerve, because thousands enthusiastically "took the cross" (i.e., vowed to go on crusade).

This raises the question of what spurred the rank and file of Europe to undertake such a long and dangerous journey. Two main factors present themselves: piety and poverty. Piety should never be downplayed in the Middle Ages, although the nature of medieval piety may have been somewhat different from our own concept of it. Crusaders went to the Holy Land believing that such a journey and the killing of non-Christians in defense of the faith would earn them forgiveness for their sins. Poverty and greed also played their role. As we have seen, Europe's expanding population created a large number of landless younger sons of nobles. Going on crusade offered them both the opportunity to win such lands and forgiveness for their sins as well. No wonder so many of them decided to undertake such a long and dangerous enterprise.

Most of those who went were nobles who needed time to get supplies for their journey and set their personal affairs in order before leaving. Therefore the departure of the First Crusade was set for August 1096 from Constantinople. This would also give the Byzantines time to prepare supplies along the line of march.

However, there were also many desperately poor peasants who had no substantial affairs to set in order. Therefore, they just set off for the Holy Land without making any plans or provisions for the march. These undisciplined mobs, known collectively as the Peasants' Crusade, gained followers and momentum in each village through which they passed. Their growing numbers also created ever mounting supply problems that often erupted into violence as they turned to pillaging for food. Such violence was often turned against local Jews, since they were non-Christian and this was a "holy war" to begin with. As a result, thousands of Jews were either killed or forced to flee their homes. However, the Jews were not the only ones upset by these peasant groups, and local populations and rulers would often turn against these unwelcome intruders. For example, three waves of peasants who went through Hungary were each destroyed by the Hungarians who were tired of their plundering.

Those who made it to the Byzantine Empire fared no better. Many were picked off on their foraging raids by Byzantine cavalry. The rest were quickly ferried across to Asia Minor to prevent further trouble in Constantinople. Not trusting the Byzantines, this undisciplined mob ignored Alexius’ advice to stay by the coast and Byzantine support. As a result, the Turks annihilated all but a few of them.

The more organized and disciplined crusading knights and nobles made their way to Constantinople in isolated groups. This allowed the emperor to deal with them singly, impressing them with his collection of relics and mechanical wonders and then extracting an oath from them to turn over any lands formerly held by the Byzantines. He would then shuttle them across to Asia Minor in time to meet the next group of crusaders arriving in Constantinople and repeat the process. These measures did help Alexius recover part of Asia Minor, notably the city of Nicaea, but they also added to growing tensions with the Crusaders who felt they were the victims of Byzantine trickery.

The crusaders saw their first serious fighting in Asia Minor. Helped by both the turmoil caused by the Assassins' murder of Malik Shah and the Turks' expectation that these European knights would be as easy a prey as the Peasants' Crusade had been, the crusaders' heavily armored shock cavalry defeated the Turks in their first major encounter. The crusaders themselves were frustrated by the Turks' mobile hit and run tactics that made it hard to win a decisive victory over them. Despite this and the intense heat, the crusaders fought their way across Asia Minor.

While the rest of the crusaders pressed into Syria, one of their leaders, Baldwin, carved out his own state around the city of Edessa using only 80 knights and some skillful diplomacy and intrigue. Naturally, this spurred the ambitions of other crusaders, in particular a Norman knight named Bohemond who had his eyes set on Antioch, one of Syria's premier cities. Antioch fell after a long grueling siege, thanks largely to the intrigues of Bohemond who then claimed the city as his own. This was the second of the crusader states to be founded as well as the source of a good deal of jealousy and quarrelling among the various crusader leaders.

The eight-month siege and stay at Antioch had decimated the Christian army through disease, hunger, and battles against various Muslim armies sent to relieve Antioch. Add to this the constant bickering between its leaders and the polyglot mixture of French, English, Germans, and Italians making up the army, and the chances of continued success did not look good. However, the rank and file in the army insisted on putting aside their quarrels and marching on Jerusalem. Finally, in June 1099, with an army of only 15,000 men, they reached their long sought goal, Jerusalem.

The crusaders endured desert heat and shortages of food and water while besieging Jerusalem. They also faced the threat of a large Egyptian army coming to relieve the city. Luckily, an Italian fleet arrived at the harbor of Jaffa, bringing the crusaders supplies and timber for siege engines. After doing penance by marching barefoot in the desert heat around Jerusalem, the crusaders launched an assault that broke into the city on July 15. What ensued was one of the worst massacres in history, spurred on by religious frenzy combined with frustration from the hardships of the last three years. Foucher de Chartres' graphic description at the top of this reading shows how the crusaders used religion to justify this ghastly event. The success of the First Crusade was a remarkable feat, but it was stained with the blood of thousands of innocent Muslims and Jews.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1187)

Despite their incredible victory, the crusaders had much going against them. First of all, they were surrounded and outnumbered by hostile Muslim states that eventually learned to unite against the Christian invaders. Secondly, since they were so far from their home base in Europe and many of the original number went back home after the conquest of Jerusalem, the remaining crusaders suffered a chronic manpower shortage, leaving them spread thinly across Syria and Palestine.

Third there was a growing cultural gap between the crusaders who stayed behind in the Holy Land and any newcomers who did arrive from Europe. They were shocked to find that after a number of years in the Near East, the original crusaders had adapted to local ways. Their clothes and houses resembled those of the Muslims. Some even kept harems with veiled women wearing makeup. More surprising yet, they set aside chapels in their churches where their Muslim neighbors could worship. Even their wars were fought in the more sophisticated local method of small local raids interrupted by truces with the Muslims. Nothing daunted, these newcomers, who had come all this way with the purpose of killing Muslims, would often break the truces, attack the Muslims, and then go home, leaving the crusaders in Palestine to bear the brunt of Muslim reprisals.

A fourth problem stemmed from the feudal system that the crusaders transplanted from Europe. Instead of one unified kingdom, they founded four separate states: the kingdom of Jerusalem and the counties of Edessa, Antioch, and Tripoli. This prevented the cooperation and unity of purpose needed against the surrounding Muslim enemies. Compounding this into a virtually hopeless situation was the further fragmentation of these states into individual baronies and fiefs.

Finally, the presence of the Italian city-states proved to be a mixed blessing. While they did provide a vital lifeline to Europe along with valuable naval support in taking the coastal cities of Palestine, this was all done for a price: the establishment of independent quarters in the coastal cities that they had helped take. This could be somewhat disruptive, since at times they might not cooperate with the crusaders in wars that could hurt their trade and business. At other times, two Italian cities might go to war with each other and the fighting would spread to those cities quarters in various crusader cities. In addition, Italian merchants also controlled much of the trade of Palestine and Syria, depriving the crusaders of much needed revenues.

Despite all these hardships, the crusader states did remarkably well, even expanding their territory in the early decades of the 1100's. Europe was still enthusiastic about the crusaders' success and kept a constant (if barely adequate) stream of reinforcements going to the Holy Land. However, as the surrounding Muslim states unified against the common enemy, the tide started to turn.

The first crusader state to fall was Edessa in 1144, which promptly triggered the Second Crusade to recover it. This crusade, led by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, tried to follow the route taken by the First Crusade. However, the heat of Asia Minor and severe supply problems decimated the crusaders' army, which was then beaten near Damascus, leaving Edessa in Muslim hands for good.

The next forty years saw Egypt and Syria become unified in a strong Muslim state under the skillful leadership of Salah-a-din. Gradually, he tightened the noose around the beleaguered crusader states and finally destroyed the crusader forces at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. Jerusalem and most of the coastal cities of Palestine and Syria soon fell into Saladin's hands.

This brought on a series of crusades that failed to take Jerusalem or hold it for any substantial time. The third Crusade (1187-92), led by the famous warrior king of England, Richard "the Lionhearted", managed to take the coastal city of Acre after a prolonged siege. However, despite a march down the coast and various exploits, including a hard fought victory against Salah-a-din at Arsuf, Richard failed to take Jerusalem. Salah-a-din did grant Christian pilgrims free access to the holy city in order to worship, something he would have been willing to do anyway.

Later crusades tended to stray further and further from their goal of Jeruslam. For example, the Fourth Crusade (1202-4) was diverted by the Venetians to Constantinople, partly to cover the cost of transporting the crusaders, and partly because of growing tensions with the Byzantines over the growing Italian stranglehold on Byzantine trade. In 1204 the Venetians and crusaders stormed and mercilessly sacked Constantinople.

Besides never reaching Palestine, the Fourth Crusade set in motion the final decline of the Byzantine Empire and deprived the crusaders of a potentially valuable ally. Relations between the Byzantines and Western Europe, which had been deteriorating for some time, grew that much worse as a result of the Fourth Crusade.

The Fifth Crusade (1228-9), led by Frederick II of Germany, did manage to negotiate the surrender of Jerusalem, but without fortifications. As a result it fell back into Muslim hands soon after Frederick returned home. The Sixth Crusade (1248-50) under Louis IX of France (Saint Louis) was directed against Egypt in the hope of being able to trade it for Palestine. The strategy would have worked except that Louis refused to negotiate with the Muslims when they were ready to give in. Then the Nile flooded, disease set in, and the entire French army was captured and forced to ransom itself from captivity. The Seventh Crusade (1270), also led by Louis IX, was directed even further afield against Tunis in North Africa. The idea was to cut off Muslim trade in the Mediterranean between Tunis and Sicily (which was held by Louis' shrewder and more practical brother, Charles of Anjou). Once again, disease did its work, this time claiming Louis, who died with the words "Jerusalem, Jerusalem" on his lips.

After this, interest in the crusades fizzled out for a couple of reasons. For one thing, Europe had changed dramatically in the 200 years since Urban II had preached the First Crusade. The rise of towns and a money economy had raised Europe's standard of living tremendously and given its people something to get interested in besides holy wars in distant lands. Also, the popes had gotten into the habit of declaring crusades against heretics in Europe (e.g., the Albigensians in France) and their mortal enemies, the German emperors. This cheapened and tarnished the image of the crusade and cost it a good deal of support.

Meanwhile, the crusader states huddled along the coast of Palestine were gradually being worn down by Muslim pressure. A brief hope of delivery seemed to present itself with the Mongols, who shattered one Muslim army after another in their rampage across Asia. However, in the Battle of Ayn Jalut (1260), the Mameluke sultan of Egypt, Baibars, crushed the Mongols and stopped their advance once and for all. This also sealed the fate of the crusaders who had encouraged the Mongols. In 1291, the last of their strongholds, Acre, fell after a desperate siege. For all intents and purposes, the age of Crusades was over.

Despite their failure, the crusades had important results. For one thing, they opened Europeans' eyes to a broader world beyond Europe, stirring interest in and a bit more tolerance of other cultures. In particular, an influx of Arab texts and translations of classical Greek and Roman literature created a more secular outlook that helped lead to the Italian Renaissance in the 1400's. The Arabs passed on knowledge in a wide array of topics ranging from math, astronomy, and geography to such techniques as papermaking and the refining of alcohol and sugar (both of which are Arabic words). On a more basic level, the Crusades stimulated an increased desire for luxury goods from the East. When they lost control of these trade routes to the Turks, they embarked upon a series of voyages of exploration in search of shorter and cheaper routes to get those luxuries. In the process, Africa was circumnavigated, Asia was more thoroughly mapped, and the Pacific Ocean, the Americas, and Australia were discovered. Thus, the Crusades, by helping lead to the Renaissance and Age of Exploration, were instrumental in opening the way to the modern world.

For the Arab world, the Crusades had less positive results. True, the Muslims ultimately won, but at a heavy price. Besides the human and material cost, there was also the psychological factor. Since c.1000 C.E., the Arab world had been assaulted by Turks, Crusaders, and Mongols. These successive invasions generated the feeling that Arabs must harden their attitude toward other cultures in order to preserve their own. In succeeding centuries, as Western Europe created its own high civilization, which has largely dominated the globe since the 1800’s, many Arabs have resisted the pressure to adapt aspects of that culture to benefit their own, an attitude that has often put them at a disadvantage in the modern world. The struggle of whether or not to modernize and make compromises with Western culture still divides the Arab world today.

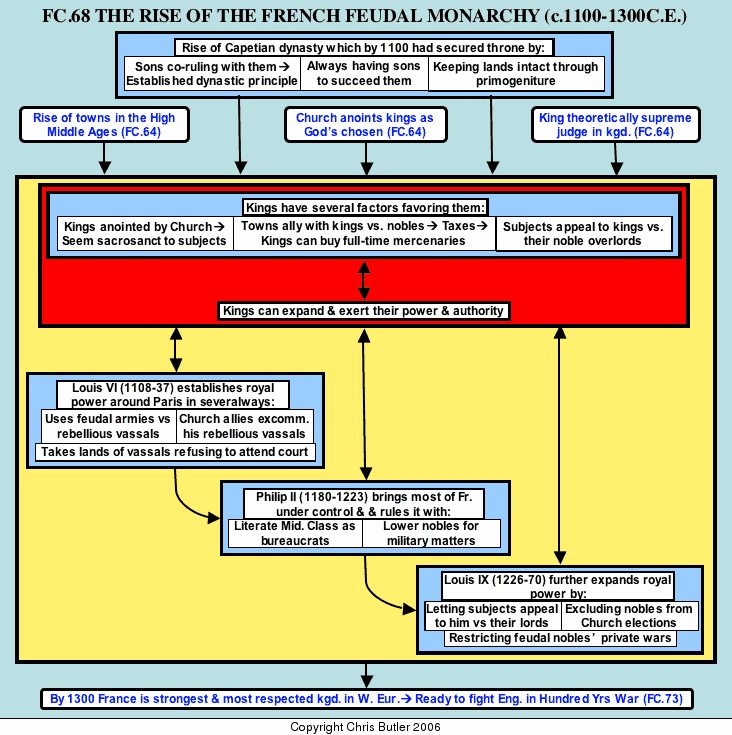

FC68Rise of the French monarchy (c.1000-1300)

In addition to the rise of towns and a money economy, the High Middle Ages also saw the development of strong feudal monarchies in Western Europe, especially in France and England. These feudal monarchies were a transition between the personal and decentralized feudal system of the Early Middle Ages and the more highly centralized nation states of the modern era. At the beginning of this era, most people may have believed in the concept of Universal Empire or Universal Church (as embodied in the Holy Roman Empire in Germany and Roman Catholic Church respectively). However, by the end of this era, it was becoming increasingly apparent that the future belonged to neither Church nor Empire, but to these newly emerging nation-states. Prominent among these was France. There were four main factors leading to the rise of the French feudal monarchy.

First of all, there was the ability of the Capetian dynasty to keep its hold on the throne, and that hinged on three things. First of all, the Capetians were lucky to consistently produce male heirs, which eliminated the need to look outside the Capetian family for a new king to succeed the old one. Second, the Capetians practiced primogeniture, ensuring that what little they controlled stayed together under one ruler, unlike the disastrous policy of earlier kings of dividing the kingdom. Finally, they ended elective monarchy by having their sons rule jointly with them, ensuring a smooth transition of power when the older king died. Over time, the Capetians gradually replaced the elective monarchy with the dynastic principle of son succeeding father to the throne.

The second factor, the medieval agricultural revolution, helped both the French kings and the great dukes and counts since they owned most of the land being cleared and could support the surplus population needed for towns. In contrast, lower nobles had neither the land to support towns nor the power to defend them.

However, the rise of towns ultimately helped kings against even the dukes and counts, because townsmen and kings were natural allies against the nobles. While the towns could supply kings with militia, their primary means of help was money with which to buy mercenaries who were much more reliable than feudal armies. Bit by bit, this alliance of towns and kings helped break the power of the nobles.

The kings' legal position as supreme judge in the land was the third factor helping them. No matter how weak a king might be, his crown distinguished him as the supreme judge whom townsmen and lower nobles could appeal to over the heads of their own lords. When kings were weak, this was done on a very local level. However, it helped kings gradually establish their power over the local nobles and assert their authority on a wider level.

Finally, there was the kings' religious position, symbolized by the Church anointing them with oil to mark them as God's chosen agents on earth. Although this raised the question of who had more authority, kings or the churchmen who anointed them, it did give the king a certain amount of religious sanctity that medieval people took very seriously. In addition, the king's sanctity also symbolized his alliance with the Church, whose powers, in particular the power of excommunication, could be very useful in bringing rebellious nobles under control. It is significant that Louis VI's right hand man was a churchman, Suger, abbot of St. Denis.

Together these factors (the Capetians' firm grip on the throne, their sacrosanct nature, their position as supreme judge, and their alliances with the towns who could also supply money with which to buy mercenaries) allowed kings to gradually expand and exert their power and authority across France. That, in turn, enhanced their judicial and religious authority, bringing them into contact with more towns that could ally with the kings and provide more taxes for mercenaries, and so on.

For over a century (987-1108) the Capetians could barely hang onto their throne, but they did manage to survive. By 1100, in addition to the king's realm around Pairs, known as the Ile de France, France's numerous independent feudal states were largely gathered into five greater feudal states: Flanders, Normandy, Toulouse, Aquitaine, and Burgundy. Even in his own small realm, the king's vassals defied him. At one point, the king was taken prisoner by a particularly unruly vassal and only rescued by the loyal militia of Paris. However, the succession of Louis VI in to the throne in 1108 marked the beginning of over two centuries of expansion for the French monarchy and the Capetian dynasty. During this time, seven kings reigned, three of who were especially capable. These three kings, Louis VI, Philip II, and Louis IX, would especially exploit the cycle mentioned above to lay the foundations for the modern French nation.

Louis VI (1108-1137), known as "the Fat" started the process of building up royal power. The first step, which he accomplished, was to establish the king's authority in his home territory around Paris. Confronting Louis were several rough and obstinate barons renown for their lawless ways. Louis had one valuable ally, Suger, abbot of St. Denis, who brought the power of the Church down against these nobles. In general we find the Church allied to the kings during this period, since both were concerned with ending the chronic violence and feudal warfare plaguing the land. Suger was a staunch and valuable ally throughout Louis' reign.

Louis' usual method was to call a noble to his court to account for the crimes his vassals and subjects accused him of. Often, the noble refused to come, giving Louis the legal excuse to claim the noble's lands now belonged to the king. Of course he had to enforce such a declaration and drive the noble off of the land. One potent weapon at the king's disposal was excommunication of the noble by the abbot Suger. This released the noble's vassals from any legal obligations to him and deprived him of some, if not all his support.

Louis still had to ride constantly with his troops from one end of his realm to the other, burning nobles' castles and wasting their lands in order to bring them to heel. It took him seven years to break the power of a certain Hugh de Puiset and sixteen years to subdue another noble, Thomas de Marley. This was because Louis had little money and had to rely on feudal armies to break his vassals. Therefore, he could accomplish little in the 40 days of campaigning he got each year. Once he was gone, the noble could rebuild any burnt castles and restore much of his power.

Still, the effects of excommunication and yearly raids gradually broke the nobles' power. By the end of Louis' reign, the Ile de France was firmly in royal control, giving the king the troops and resources to expand even further. Louis' prestige was enhanced to the point that he was able to restore the infant lord of Bourbon and bishop of Clermont to their rightful places. He was even able to arrange a marriage alliance between his son and Eleanor, daughter and heiress of William X, the powerful duke of Aquitaine. Much of the subsequent history of France and England would revolve round this woman.

When Eleanor of Aquitaine married Louis VII (1137-80), she claimed she married a king only to find him a monk. Eleanor's fun loving ways certainly clashed with the pious king's personality and eventually led to getting the marriage annulled. Not only did this cost Louis the valuable lands of Aquitaine, it let Eleanor marry Henry II of England. The result of this union was what is known as the Angevin Empire, whereby the king of England controlled Aquitaine in addition to his hereditary lands of Normandy and Anjou (hence the name Angevin). This gave Henry II control of one-third of France, much more than the king of France, his nominal overlord, ruled. However, the size of Henry's empire alarmed other French nobles and drove them to support Louis. At the time the English holdings seemed like a threat to the very existence of the French monarchy. The next French king, Philip II, would destroy this threat.

Philip II (1180-1223), called "Augustus", was certainly one of the greatest of French monarchs, being responsible for establishing the French monarchy as the recognized power throughout most of France. He was an astute and unscrupulous diplomat, though not a great general. In the early years of his reign he was lucky to maintain his own against Henry II, his main tactic being to stir Henry's rebellious sons against their father. Philip had little luck against the warrior king Richard I "the Lion-hearted" (1189-99). His luck was better against Richard's brother and successor John I (1199-1216) of Robin Hood fame.

Philip skillfully used his position as John's overlord in France to bring charges against John and summon him to court. Of course, John refused and Philip declared John's lands forfeit and now belonging to the French crown. War resulted in which a powerful coalition of England, Flanders and Germany was formed against Philip. Luckily for Philip, John moved too slowly and the French king was able to crush the Flemish and German forces at Bouvines in 1214.

This battle had far reaching consequences for France, England and Germany. In France it tripled the size of the king's realm at one stroke while driving the English out of France except for Bordeaux and Bayonne. The blow to king John's prestige was such that the next year the English barons rebelled and forced John to sign the Magna Charta, one of the cornerstones of British and American democracy. Bouvines also helped some with the disintegration of the German monarchy, as we shall see.

However, our main concern here is Philip's victory and what he did with it. Not since Charlemagne had any ruler so effectively controlled France. However, times had changed, and Philip found he had different and more effective means for ruling France than Charlemagne had. Whereas Charlemagne had been forced to rely on giving land to uneducated nobles in return for service, Philip had money and an educated middle class at his disposal to help him rule. As a result he started putting middle class baillis (bailiffs) paid with money, not land, to administer his far-flung state for him. Such baillis were loyal to him and were kept in line by the threat of the king cutting off their salaries. Also their lower social status made them less likely to try to gain power for themselves. Philip rotated them from place to place so they would not get established in one area. Since soldiers would not follow middle class baillis in battle, any offices requiring military duties were filled by lower nobles called seneschals. Being lower nobles, they were less likely to rebel, although their power and prestige could increase after years of service with the king.

The size of the king's realm and its efficient administration provided him with money that allowed him to hire mercenaries who helped him further increase his power within his realm and in areas of France still outside it. This of course gave him more revenues that allowed him to further increase his power, and so on. Philip II made the French monarchy the most powerful and respected in Western Europe. The work of his successors mainly embellished upon what he had accomplished. Keep in mind, however, that Philip was building on the foundations laid by Louis VI. Still, it is safe to say that Philip II's reign was a major turning point in French history.

Louis VIII (1223-26) made one significant innovation: the appanage system whereby younger sons of the king were given lands (appanages) to rule in the king's name. These princes were not independent rulers in their own right, such as happened with earlier Frankish kings. But the system did have its dangers, as seen by the appanage of Burgundy, which almost established itself as an independent power in the 1400's. The appanage system shows the limits of medieval government. Since royal power and prestige still depended largely on dealing with affairs in person and the king could not be everywhere at once, members of the royal family were the next best choice for enforcing royal control. Despite its dangers, the appanage system worked fairly well.

Louis IX (1226-70), known as Saint Louis, extended royal power even further. He asserted that lower nobles could appeal directly to the king's courts over the heads of their immediate lords. Nobles were excluded from interfering with Church elections. He also hemmed in the nobles by outlawing trial by combat and making restrictive rules that took the "fun" out of feudal warfare. Nobles could not slaughter peasants or burn their crops. They had to give enemies notice of impending attacks and had to grant truces when asked to do so. Royal officials scoured the land to enforce these rules. Louis also launched two disastrous crusades that deprived France of many of its troublesome nobles, although that was not his intention. Bit by bit, peace and order were replacing feudal anarchy in France, which by 1300 was the most powerful and respected state in Western Europe.

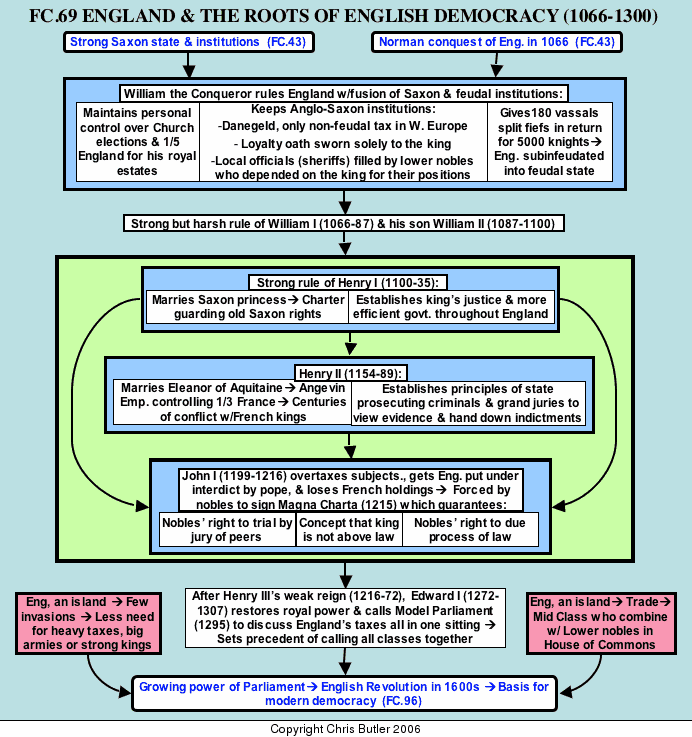

FC69Anglo-Norman England (1066-1300)