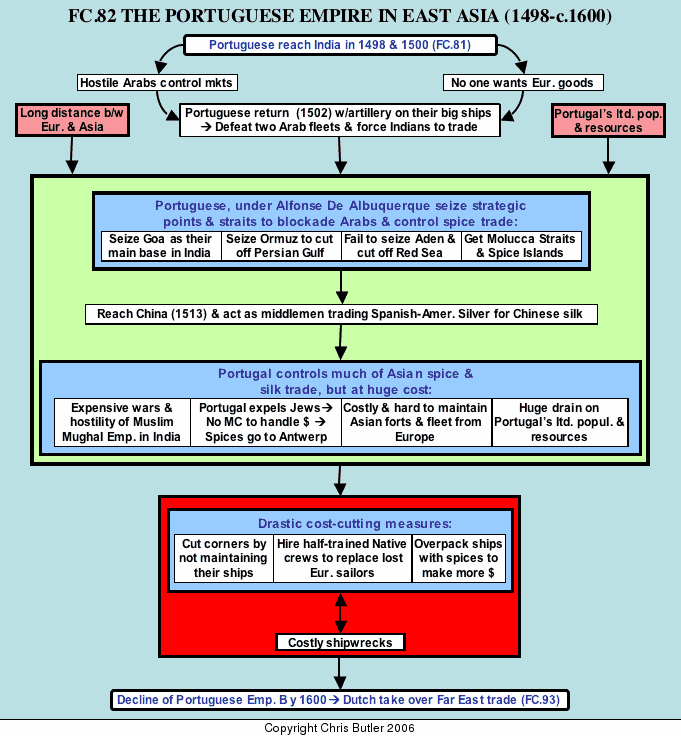

FC82The Portuguese Empire in the East (c.1500-1600)

Even before da Gama had set out for India, a Genoese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag, Christopher Columbus, had returned from what he believed was a direct route to Asia. This provoked a dispute between Spain and Portugal over who could claim what territories outside of Europe. In 1494, the pope arbitrated the dispute and drew a Line of Demarcation down the middle of the Atlantic. Everything outside of Christian Europe and west of the line belonged to Spain; everything east of it was Portugal's to claim. The line extended all around the globe, but since the size of the earth was not known, just where that line came out was anybody's guess. Despite these uncertainties, the Pope's Line of Demarcation determined the direction of both Spanish and Portuguese explorations. For the Portuguese, this meant they must control the trade routes to the East.

In 1500, only a year after da Gama's return, Pero Alvares Cabral followed da Gama's route to India with a fleet of ten Portuguese ships. Using da Gama' tactic of swinging westward to pick up westerly winds to take him around the Cape of Good Hope, he accidentally hit Brazil which juts eastward into the Atlantic. Since that part of Brazil lay east of the Line of Demarcation, Cabral claimed it for Portugal. He continued to India, but found the same problems da Gama had encountered: Arab hostility and an unwillingness to trade for European goods.

Therefore, the Portuguese decided to change their approach. The third expedition to India, led by da Gama in 1502, took 14 well-armed ships that would take the spice trade by force. The bulky European ships, built to stand the rough Atlantic seas, also provided excellent gun platforms for artillery, and that was the decisive factor in the battle that followed as the Portuguese beat the Arab fleet opposing them. A second decisive victory by the Portuguese fleet in 1509 established the Portuguese reputation for naval invincibility in Eastern waters and started Portugal on the road to establishing a maritime empire in the East.

The architect of the Portuguese Empire in the East was a capable and daring leader, Alphonse de Albuquerque. He realized that such a tiny state as Portugal could not conquer a land empire in Asia and run it all the way from Europe. Therefore, he concentrated on seizing key strategically placed ports that could control the flow of the spice trade. First he captured the strongly fortified island of Goa off the coast of India. From there he could strike out in several directions. Although he failed to cut off Muslim trade coming out of the Red Sea, he did cut off much of the Arab trade by seizing Ormuz at the tip of the Persian Gulf through some masterful bluffing and sailing with only six ships.

The Portuguese maintained their dominance of the East through a combination of astute and ruthless policies. Albuquerque was especially talented in establishing the proper ratio of escort ships to cargo ships. The Portuguese also blackmailed other merchants into paying for certificates of free passage in the Far East. For a few years they managed to have nearly all spices headed for Europe traveling on Portuguese ships.

However, there were serious limits to Portugal's power in the East, which led to the eventual decline of its Empire in Asia. For one thing, the Portuguese, in a fit of religious fervor, had expelled their Jewish bankers and merchants from Portugal, thus eliminating most of Portugal's business community. As a result, the Flemish port of Antwerp handled most of Portugal's spice trade and took much of its profit. Second, Portugal's empire put a tremendous strain on its very limited manpower. Along these same lines, it was very expensive to maintain forts, garrisons, and fleets, especially over such long distances. Finally, the hostility of local rulers, in particular the Mughal Dynasty ruling India, put extra strains on Portugal's ability to hold its empire.

All these factors cut deeply into Portugal's profits and prompted several cost cutting moves. The Portuguese cut corners by not maintaining their ships in the best condition. They would replace lost European crewmen with half-trained natives unfamiliar with European ships and rigging. Finally, because of the limited number of ships and the desire for as large a profit as possible, they would over pack their ships with spices. All these measures led to costly shipwrecks, which cut further into Portuguese profits and caused even more of these cost cutting measures. By 1600, the Portuguese Empire in Asia was in serious decline and increasingly losing ground, first to the Dutch and later to the English.