FC93The Rise of the Dutch Republic in the 1600's

Introduction

Although it took the Dutch until 1648 to force formal recognition of their independence from Spain, for all intents and purposes, the Dutch Republic was free by the twelve-year truce signed with Spain in 1609. The question arises: how did the Dutch hold off and defeat the biggest military power in Europe? While geographic distance from Spain, foreign aid from France and England, and the occasional desperate measure of opening their dikes to flood out invading armies all certainly played a role, the single most important factor was money. For example, of the 132 military companies in the Dutch army in 1600, only 17 were actually made up of Dutch soldiers. The rest were English (43), French (32), Scottish (20), Walloon (11), and German (9) companies fighting for the Dutch because they had the money to pay them. The war took a tremendous financial effort to win, costing the Dutch 960,000 florins in 1579, 5.5 million florins in 1599, and 18.8 million florins in 1640. Despite this expense, the Dutch were in stronger financial shape than ever by the end of the war and were well on their way to becoming the dominant commercial and economic power in Europe. This economic dominance was the product of a chain reaction of events and processes that, as so often was the case, was rooted in geography.

Geography of the Netherlands

Three geographic factors influenced the rise of the Dutch Republic. First, as the name Netherlands (literally "lowlands") implies, much of the Dutch Republic is below sea level. The Dutch have waged a constant battle in order to claim, reclaim, and preserve their lands from the sea through the construction of dikes, polders (drained lakes and bogs), drainage systems, and windmills (for pumping out water). Roughly 25% of present day Holland is land reclaimed from the sea and still partially protected by hundreds of windmills. The second factor is the Netherlands' position at the mouths of several major rivers and on the routes between the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean. The third factor is the Netherlands' relative scarcity of natural resources. All three of these factors forced the Dutch to be resourceful engineers, merchants, sailors, and artisans. With these geographic factors as a foundation, the Dutch launched themselves on a career that was a classic case of the old saying: it takes money to make money. The whole process started with fish.

In the 1400's, the herring shoals, a mainstay of the Hanseatic League, migrated from the Baltic to North Sea. The Hanseatic League's loss was the Dutch Republic's gain, since, in the absence of refrigeration, salted herring was then an important source of protein in Europe, especially the Netherlands whose population was 40% urban and had to import about 25% of its food. The other half of this trade was salt for preserving the herring. The best sources of salt were off the coasts of France (the Bay of Biscay) and Portugal. These two activities complemented each other well, since the herring season lasted from June to December, so the Dutch could collect salt from December to June.

The Dutch ran large scale operations compared to those of other countries. Unlike the simple open English fishing boats, the Dutch sailed virtual floating factories, called buses, with barrels of salt for curing the herring on board. Although the claims by other competing countries that the Dutch had 3000 ships working the herring shoals were vastly exaggerated (500 being closer to the mark), the Dutch still produced such a volume of salted herring that they could undersell their competition and drive them out of business.

The Dutch pattern of growth

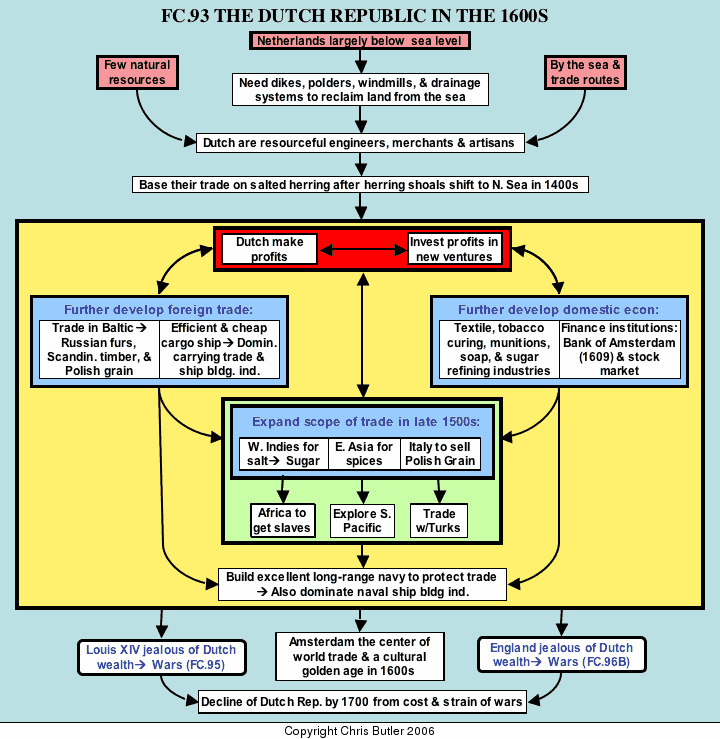

Dutch control of the herring trade touched off a cycle where the Dutch would get profits, invest those profits in new ventures, which generated more profits and so on. This initially led into two general areas of development, foreign trade and the domestic economy, each of which fed back into the cycle of profits and so on. Both of these also led to expansion of trade across the globe to the Mediterranean, West Indies, Africa, East Indies, and the South Pacific, which also fed back into the cycle of profits.

In terms of foreign trade, the Dutch first expanded their operations into the Baltic Sea where they traded for Norwegian timber, Polish grain, and Russian furs for both home consumption and selling abroad. The Baltic trade became so important that the Dutch referred to it as the "Mother Trade."

All this trade required durable, efficient, and cheaply built ships that could operate in the rough waters of the North and Baltic Seas as well as the shallow coastal waterways that were typical of the Netherlands. What the Dutch came up with was the fluyt , a marvel of Dutch efficiency and engineering. The fluyt was both sturdy enough to withstand rough seas and shallow draught for inland waterways. Unlike other countries' merchant ships, which doubled as warships, the fluyt carried few, if any, guns, leaving extra space for cargo. It was cheaper to build, costing little more than half as much as other ships, thanks to the use of mechanical cranes, wind-driven saws, and overall superior shipbuilding techniques.

The fluyt also had simpler rigging that used winches and tackles, thus requiring a crew of only 10 men compared to 20-30 on other European ships. This resulted in two things. First of all, the Dutch could carry and sell goods for half the price their competition had to charge, giving them control of Europe's carrying trade. Second, they were able to dominate Europe's shipbuilding industry.

Meanwhile, the Dutch were developing their domestic economy in two ways. First they invested in a wide variety of industries, some traditional and some new: textiles, munitions, soap boiling, sugar refining, tobacco curing, glass, and diamond cutting. The need for efficient handling of all the money from this and other enterprises spurred the Dutch to develop another aspect of their economy: financial institutions For one thing, they established the Bank of Amsterdam in 1609, the first public bank in North-West Europe, being modeled after the Bank of Venice (f.1587). The vast sums of cash this bank attracted in deposits allowed it to lower interest rates, which in turn brought in more investments, and so on. Even in wartime, the Bank of Amsterdam was able to lower its interest rates from 12% to 4%. The Dutch also created a stock market. At first this was just a commodities market. Only later did it evolve into a futures commodities market where, by the time a shipload of such goods as wool or tobacco landed, someone had already bought it in the hope of reselling it for a profit.

The success of the Baltic Mother Trade and their domestic economy led the Dutch to expand their foreign trade on a global scale. They did this in three basic directions. First was the Mediterranean, where recurring famines hit in the 1590's, signaling the start of a "Little Ice Age" that would afflict Europe for the next century. This opened new markets for Polish grain, which the Dutch traded in return for, among other things, marble. (It was this Italian marble which Louis XIV would buy from the Dutch for his palace at Versailles.) The Dutch even expanded this Mediterranean trade to include doing business with the Ottoman Turks.

Second, when Portugal (then under Spain's rule) closed access to its supplies of salt, the Dutch crossed the Atlantic to find salt in Venezuela. While there, they found the plantations in the West Indies needed slaves, which got them involved in the African slave trade. They also discovered an even more lucrative condiment in the Caribbean than salt: sugar. Soon, the Dutch were founding their own colonies (e.g., Dutch Guiana) and sugar plantations and gaining control of the sugar trade. Soon, sugar was rivaling even the spices of the Far East in value. However, this is not to say the Dutch ignored the Far Eastern trade.

However, breaking into the lucrative Asian Spice market, the third new direction of Dutch expansion, was not so easy. For one thing, they had to find the East Indies. Amazingly, the Portuguese had kept the South East Passage around Africa a secret for a full century since da Gama's epic voyage. The Dutch looked in vain for a northeast passage around Russia. They also sought a southwest passage, which Oliver van der Noort found (1599-1601), making him the third captain to circumnavigate the globe after Ferdinand Magellan and Sir Francis Drake. But that route was no more practical for the Dutch than it had been for the Spanish and English.

Finally, Jan van Linschuten, a Dutch captain who had served Portugal, showed the way around Africa in 1597. Although the first voyage was not a financial success, the second was, bringing back 600,000 pounds of pepper and 250,000 pounds of cloves worth 1.6 million florins, double the initial investment. Investors rushed to get in on the action, forming the Dutch East Indies Company in 1602. This privately owned company operated virtually as an independent state, seizing control of the spice trade from Portugal's weakening grip. From there, always in search of new markets, the Dutch explored the South Pacific, discovering Australia, New Zealand, and Tasmania, the last two names bearing evidence of their presence.

Such a far-flung trading empire, combined with the struggle with Spain, required a navy to protect its merchant ships. Therefore, the Dutch developed such a navy, excelling in this as well as their other endeavors. At this point, warships generally followed the principle of the bigger the better. As a result, the man-of-war, as it was called, was a huge and bulky gun platform that did not suit the Dutch needs. For one thing, they needed more of a shallow draught vessel that could sail in their home waters. They also needed a long-range ship that could protect their far-flung commercial interests. The result was the frigate, a sleeker shallow draught vessel with only about 40 guns, but capable of long-range voyages. Dutch frigates, along with their excellent sailors and captains, made the Dutch the supreme naval power of the early 1600's and also helped them dominate the warship-building industry, building navies for both sides in a Danish-Swedish war and even for their French rivals. And, of course, this brought in more money and pushed the Dutch to expand their domestic industries and finance operations in three ways.

A cultural golden age

By the early 1600's, Amsterdam was the center of world trade, which allowed the Dutch to engage in one more type of activity: patronage of the arts. The seventeenth century saw the Dutch Republic become the center of a cultural flowering much as Italy had been during its Renaissance. Along with money to patronize the arts and sciences, the Dutch Republic had both a free and tolerant atmosphere and enterprising spirit willing to challenge old notions and creatively expand the frontiers of the arts and sciences. The Dutch Republic acted as a virtual magnet for Jewish émigrés from Spain and Portugal and Calvinist dissidents from England, some of who would eventually move on to Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts. The Jewish philosopher from Spain, Spinoza, and the French mathematician, Descartes, were two of the shining lights that the Dutch attracted. Notable among Dutch artists were Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hals, Van Dyck, Steen, Ruysdael, and Hobbema, whose portraits, domestic scenes, landscapes, and mastery of light and shadow brought their age to life on the canvass as no artists before them had done.

Conclusion

The Golden Age of the Dutch Republic was to be short lived, once again largely because of geography. It was the Dutch Republic's great misfortune to border the great land power of the day, France. In the 1670's, the French king, Louis XIV, due to a combination of jealousy of Dutch prosperity and hatred of Protestants, launched a series of wars that would embroil most of Europe and put the Dutch constantly on the front line of battle. At the same time, just across the channel, the growing economic and naval power, England, was challenging the Dutch on the high seas and in the market place. Three brief but sharply fought naval wars plus the strain of fighting off Louis exhausted the Dutch and allowed England to become the premier economic, naval, and colonial power in the world by the 1700's. However, England owed the techniques and innovations for much of what it would accomplish in business and naval development to the Dutch from the previous century.