FC96AJames I, Charles I, and the Road to the English Civil War (1603-1642)

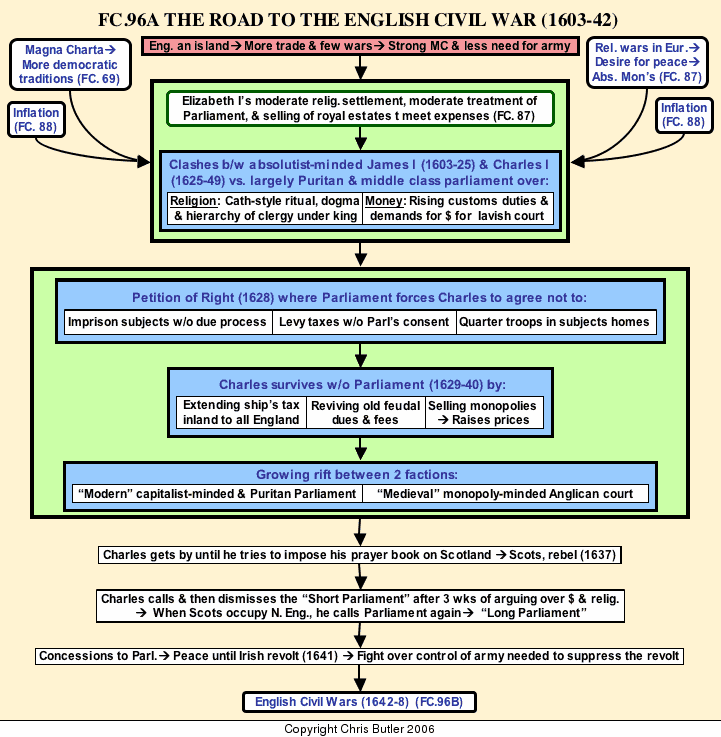

James I (1603-25), Elizabeth I's successor (who also ruled Scotland as James VI), was much more overbearing and prone to make enemies than Elizabeth had been. He lectured Parliament on the Divine Right of Kings and even wrote a treatise on it, The Trew Law of Free Monarchies. Such an attitude did not set too well with Parliament. James' abrasive manner, absolutist beliefs, more Catholic concept of what the Church of England should be, and demands for money to support his lavish lifestyle made him many enemies who dubbed him the "most learned fool in Christendom."

In religious matters, the king headed the High Commission, which exercised powers of censorship and excommunication and appointed the higher clergy who in turn chose the local clergy. News of the outside world came mainly from the clergy who got their news from the higher clergy and ultimately the king. As Charles I: put it: "People are governed by the pulpit more than the sword in times of peace." No wonder that religion became the main focal point of trouble at this time. There was also the issue of observing the Sabbath. Puritans felt that Sundays should be reserved for strictly religious activities and discussions. The king, fearing that such discussions might breed revolution, encouraged more frivolous sports on Sundays to keep people militarily fit and harmlessly occupied. Such a policy outraged the Puritans and turned them further against the king.

Money was the other big source of conflict, and the House of Commons in Parliament was the primary battlefield. Among Parliament's most jealously guarded liberties was the right to grant taxes. This had not been such a vital issue when kings could largely get by on the revenue from their estates, various feudal fees, and the right to sell monopolies and titles. However, inflation further reduced the value of the royal estates after Elizabeth sold a quarter of them, James own extravagant lifestyle and the rising cost of warfare in the 1500's and early 1600's led to growing friction between king and Parliament over money.

Parliament then was not so democratic in makeup as today. Even the House of Commons consisted solely of gentry (lower nobles) and merchants with an annual income of at least 40 shillings, a sizable sum back then. The rights and privileges they jealously guarded and fought for, such as immunity from arrest and flogging and the right to free speech, were reserved for them alone, not the lower 90% of society. As one Member of Parliament put it: "He that hath no prosperity in his goods is not free." Still, the rights and privileges Parliament fought for and won in the 1600's set a precedent, and eventually would extend to all of society.

James did have one growing source of revenue: customs duties from a rapidly expanding foreign trade. In order to take advantage of this, James raised the taxable value of various commodities to keep up with their real market value, which had risen due to inflation. Naturally, the merchants in Parliament disliked this tactic and disputed James' right to revise those values without Parliament's consent.

Further aggravating James' problems was the lack of an efficient bureaucracy such as was developing in continental states. Taxes were collected by tax farming, where local merchants paid a lump sum to the king in advance and then collected however many taxes they could get away with. This, of course, led to lower royal revenues, more corruption, and rising tensions.

Thus the stage was set for a conflict between the king on one side and Parliament and the Puritans on the other. During James' reign, relations with Parliament were generally stormy. Constant haggling over money and such religious issues as the existence of bishops in the Church of England would reach fever pitch and then subside with an occasional compromise to patch things up. There was even a temporary alliance between king and Parliament when a proposed marriage alliance with Spain (which was very unpopular with Parliament) fell through and got England involved in the broader conflict known as the Thirty Years War. For the time being, this drove king and Parliament together against the common Catholic enemy. However, the overall situation was deteriorating, and by James' death in 1625, relations between the two parties were, at best, strained.

It was said that James steered the ship of state for the rocks, but left it for his son, Charles I, to wreck it. Charles was undiplomatic, insensitive to public opinion, and a weak monarch who let events get out of control and send England drifting toward civil war. Charles, like his father, was largely a victim of the times, being caught between rising prices and the rising aspirations of Parliament and the Puritans on the one hand and his own ideas favoring Catholicism and absolutism on the other. Charles even resorted to forcing loans out of men and imprisoning those who refused to cooperate. In 1628 Parliament reacted by forcing Charles to sign the Petition of Right in which he agreed not to levy taxes without Parliament's consent, imprison free men without due process of law, or quarter his troops with private citizens. After this, he dissolved Parliament and ruled on his own.

For the next eleven years (1629-40) Charles managed to get by without Parliament by stretching various royal rights and fees to the limit. One of these methods was selling monopolies. Under this system only the man who bought a monopoly on a particular type of goods had the exclusive right to sell or grant the right to others to sell those goods. This wreaked havoc with prices and caused a good deal of discontent, especially since the monopolists controlled a wide range of products including buttons, pins, dyes, butter, tin, beer, barrels, tobacco, dice, pens, paper, gunpowder, feathers, soap, lace, and hay to name just a few. Another method was extending the traditional ship's tax (previously levied only on coastal towns) to the whole countryside. As unpopular as these measures were, they raised the king his money and kept him going.

Charles might have continued like this indefinitely, but in 1637, he tried to impose the English Prayer Book on the Scots and triggered a revolt instead. Unfortunately for Charles, many of the Scots were battle-hardened veterans from the Thirty Years War who made short work of his largely untrained rabble. Desperately in need of money to continue his war, Charles called Parliament in 1640. However, after three weeks of arguing with Parliament over the last eleven years' religious and monetary policies, the king dismissed this "Short Parliament." However, the Scots did not go away. Instead, they occupied part of the north and made Charles promise a large sum of money every day until a final settlement was reached. Charles had no choice but to call Parliament again. This Parliament is known to history as the Long Parliament, because it would sit for over a decade and preside over a civil war and the end of absolute monarchy in England.

The events leading to civil war were a bit more straightforward. Charles, desperate for money and support to take care of the Scots, initially agreed to Parliament's demands. He would not levy taxes or dismiss Parliament without its consent. And he would agree to call Parliament at least every three years. He even let Parliament execute one of his chief ministers, Sir Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford.

However, there was hardly peace between king and Parliament, only an uneasy truce. In November 1641, a spark was struck which led to civil war. A revolt broke out in Ireland, with Irish Catholics killing thousands of English and Scottish Protestants who had taken their best lands. An army was needed, but neither king nor Parliament was going to allow the other to command such an army. When Parliament refused Charles his army, he sent troops in to arrest five Parliamentary leaders. They found refuge in London and support from other towns. Charles left London, and by August 1642, England had plunged into civil war.