Early Chinese CivilizationUnit 8: Early Chinese Civilization

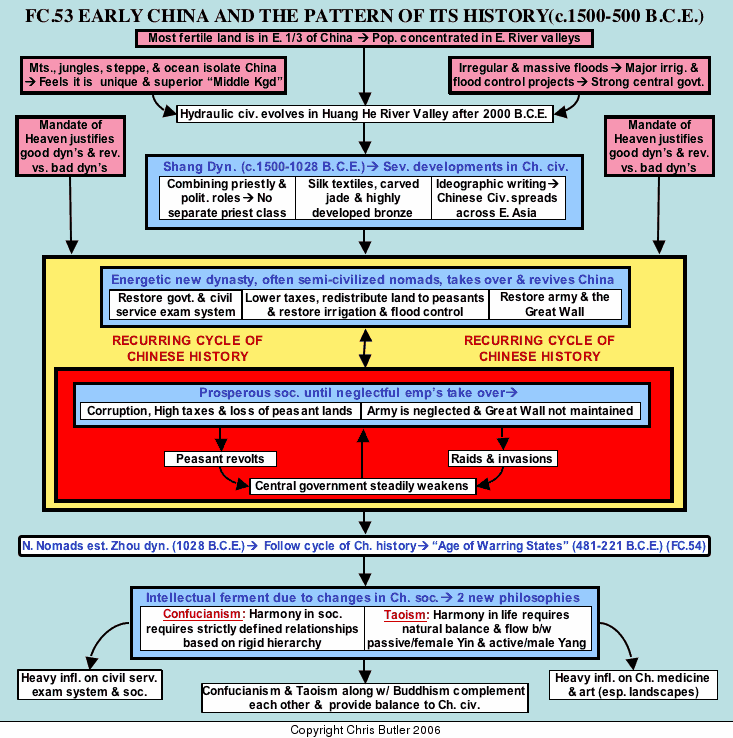

FC53Early China (1500-221 BCE) and the recurring pattern of Chinese history

With harmony at home there will be order in the nation. With order in the nation there will be peace in the world.— Confucius

The geographic factor

Far to the east of the civilizations developing in Egypt and Mesopotamia another great hydraulic civilization, China, was evolving. As with Egypt and Mesopotamia, geography heavily influenced the development of Chinese civilization. For one thing, the eastward flow of the rivers from the mountains in the west also meant that China's most fertile land was in the coastal lowlands in the east. Even today, 80% of China's population lives in the eastern third of the country. Throughout its history, this factor has given China a vast concentrated reservoir of human resources to draw upon for its wealth and power.

Secondly, China is largely isolated from the rest of the world by rain forests to the south, some of the highest mountains in the world to the west, the Pacific Ocean to the east, and vast grasslands (steppe) and deserts to the north. Direct contact with other civilizations would be rare, although occasional influences have passed back and forth between China and the rest of the world with profound effects. For the most part, however, China evolved largely in isolation and saw itself as the "Middle Kingdom", both unique and superior to other cultures. This attitude would create difficulties, especially in the modern era when growing contact with the outside world forced China to deal with different cultures.

Another dominant feature of China's geography has been its rivers, in particular the Huang He (Yellow), Yangtze, and Xi Jiang. The Yellow River valley in the north was particularly important as the birthplace of Chinese civilization, because its irregular rainfall and devastating floods forced the Chinese to organize massive irrigation and flood control projects. Such organization required a strict hierarchy of authority, which influenced subsequent Chinese history.

The Shang Dynasty (c.1500-1028 B.C.E.)

By 1500 B.C.E., China's geography helped lead to one of history's early hydraulic civilizations in the Yellow River Valley under the Shang, the first of the dynasties into which Chinese history is traditionally divided. The Shang and various local nobles who ruled in their name combined both government and priestly functions. As a result, no distinct or elaborate class of priests emerged in China as happened in other early civilizations such as Mesopotamia and Egypt.

China saw several technical developments during the Shang period in the way of silk textiles, carving in ivory and jade, and especially bronze technology. Bronze artifacts from the Shang period are some of the finest examples of metalworking found in any Bronze Age culture. Among those artifacts were bronze arms and armor which, along with the horse drawn chariot, gave Shang armies an edge over their enemies and allowed the expansion of Chinese civilization.

Another advance during this time was writing. Chinese writing was and remains ideographic, being based on pictures rather than sounds. Such a script required many more symbols to memorize, making it harder to read and seriously restricting the number of literate people. However, ideographic writing had one benefit. Since it was not based on the sounds of any particular language, it was readily adaptable to different dialects of Chinese and even non-Chinese languages in East Asia such as Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. As a result, Chinese culture spread and became the predominant cultural influence across East Asia.

The pattern of Chinese history

A basic recurring pattern has repeated itself throughout Chinese history. A new dynasty would take over and revive Chinese civilization in two ways. First, it would restore the army, the Great Wall, government and bureaucracy. It would also lower taxes, redistribute land to the peasants, and rebuild the irrigation and flood control systems. Together, these would create a strong and prosperous society until lazy emperors took over and neglected their duties, allowing corrupt officials, high taxes, powerful nobles who took the peasants' lands, and the decay of the army and Great Wall. This would lead to peasant revolts from within and raids and invasions from without that together would weaken the government, causing more corruption, high taxes, military decay, and powerful nobles oppressing the peasants. Eventually, a new dynasty would seize power and start the cycle over again.

One concept combining religion and politics that was central to this process and China's political thinking was the Mandate of Heaven. This said that a ruling dynasty had the mandate or approval of Heaven to rule as long as there was peace and prosperity. However, natural and man-made disasters were signs that the dynasty was not doing its job and that the mandate had been withdrawn and passed to a new dynasty. Thus the Mandate of Heaven was a double-edged sword, justifying the power and rule of a successful dynasty on the one hand, but also justifying revolution when things went wrong.

The Zhou Dynasty (1028-256 B.C.E.)

The Shang Dynasty prospered until weak rulers allowed the realm to fragment into various warlord states. Eventually, this situation enticed nomadic tribes from the North-west to come in. One of these tribes, the Zhou, eventually assumed power as the next dynasty to rule China.

By 700 B.C.E., the Zhou had succumbed to the temptation of the softer cities in the East and gone into decline. Powerful warlords carved out their own principalities while giving the Zhou emperors only nominal allegiance. Naturally, these warlords turned on each other with increasing ferocity in a period known as the age of "the Warring States" (481-221 B.C.E.). However, despite this turmoil, Chinese civilization continued to spread and advance thanks to several innovations. First of all, the use of gold and copper coins replacing such things as shells and rolls of silk as the primary mediums of exchange made trade much easier and put more wealth into circulation. Secondly, the use of oxen to draw plows and the introduction of iron farm implements enabled Chinese peasants to clear more land, produce more food, and raise China's population and wealth dramatically.

Confucianism and Taoism

Still, this was a turbulent period which sparked a good deal of intellectual ferment, leading to two very different philosophies that together would become essential parts of Chinese culture: Confucianism and Taoism.

Kung Fu-tzu (known to the West as Confucius) was born in 551 B.C.E. He started his career as a government official, but later became a traveling teacher who attracted many students. He saw the key to China's stability in a strict observance of rituals and traditions. Among these rituals was ancestor worship, which had been an integral part of Chinese religion for centuries. However, Confucianism was not a religion, but rather a systematic philosophy for maintaining peace and harmony in this world. (Confucius himself said that he knew too little about this world to even begin worrying about the next. That would have to take care of itself in due time.) Central to Confucius' philosophy was a strict hierarchy of relationships, the five most important being those between ruler and ruled, father and son, husband and wife, older and younger brother, and friend and friend. As long as the proper conduct and respect took place in these relationships, overall harmony would prevail. As Confucius saw it, a harmonious society rested firmly on a harmonious family structure. Confucius also advocated a civil service that got its positions through merit (in particular education and knowledge of the classics) rather than through birth or personal connections. Although not too popular in his own day, Confucius' ideas later had a profound impact on Chinese government and society that carry on to the present day.

Lao-tze (600's B.C.E.) founded the other great Chinese philosophy of the day, Taoism, which differed from Confucianism much as night differs from day. Whereas Confucianism provided a very strict framework for dealing with civilized society, Lao-tze advocated escape from that society and a return to our natural state through contemplation of the Tao (the Way), the cosmic principle through which the harmony of the universe was maintained. He saw everything in nature and the universe as being balanced between two complementary forces: the active male Yang ("sunlit") and the passive female Yin ("shaded"). Rather than seeing one as superior to the other, Lao-tze saw a truly healthy and harmonious person or society as being perfectly balanced between the active Yang and passive Yin. An example of this is the Chinese martial art, Tai Chi, which strives to use an opponent's own strength and force to knock him off balance. Lao-tze saw disease, floods, famines and wars as the result of an imbalance in nature, often caused by human actions. By the same token, any attempts to conform to strict government or personal codes of discipline were artificial and deformed human nature. Taoist ideas would strongly influence Chinese art, especially landscape painting, medicine with its idea of keeping a body in balance, and even Sun-tzu's Art of War that advocated dexterity and balance in conformity with nature rather than merely the use of brute force.

As different as Confucianism and Taoism were, they each had a profound impact on Chinese culture. Later, with the addition of Buddhism, the three philosophies would be known as the Three Doctrines. However, rather than competing with one another, each philosophy would fulfill a particular need in China's culture. Together they would give it a balance that would make it uniquely Chinese.

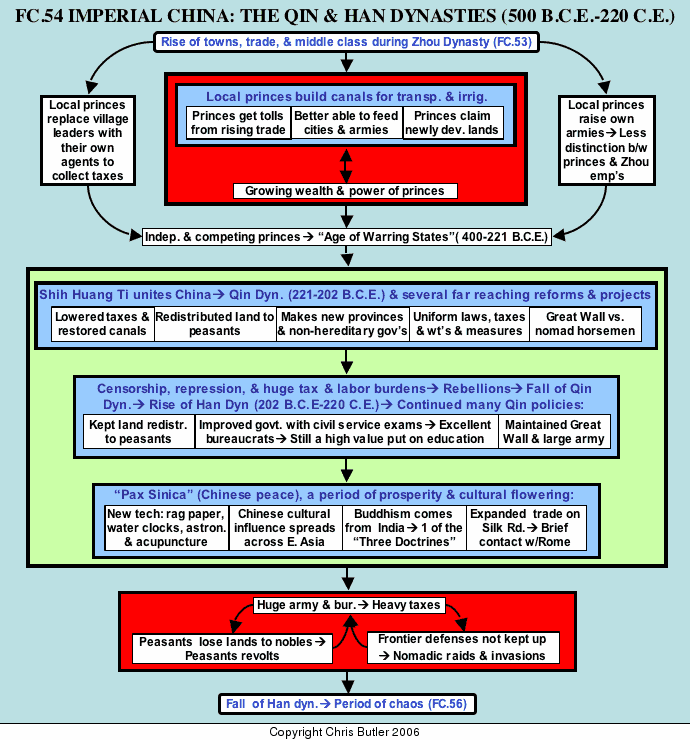

FC54The Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE-220 CE

You won the world from horseback, but can you rule it from horseback?— Minister to Liu Pang, founder of the Han dynasty

The Later Zhou (772-221 B.C.E.)

The early period of the Zhou dynasty, known as "Spring and Autumn" (722-481 B.C.), saw relative stability and the growth of trade, towns, and a middle class of merchants and artisans. However, this prosperity contained the seeds of the Zhou’s decline, since it gave local princes in the provinces the resources to do three things. First, they built canals which themselves had three effects. For one thing, they further increased trade, thus giving the princes more tolls and taxes. They also improved transportation of grain, allowing them to feed their cities, armies, and bureaucrats better. And finally, they led to the cultivation of new lands that the princes could claim for themselves. Together, these effects gave the princes more wealth and power that they could use to develop more canals and so on.

Secondly, princes and local nobles started appointing their own agents to collect taxes instead of doing it indirectly through local village leaders, as had been the custom. Finally, the princes started arming peasants and using them in their armies alongside the traditional feudal levies supplied by their vassals. This especially reduced the distinction between the Zhou emperors and their princely subjects in the provinces.

Together, these developments gave the princes more control over their own local nobles and establish more tightly centralized states. This in turn led to increased warfare between the princes who now had much greater resources for waging war than before. With larger armies using peasant levies as well as noble warriors, the intensity of fighting increased and the old courtesies of warfare and diplomacy that had governed relations between princes and nobles disappeared. The resulting chaos, known as the age of "Warring States" (481-221 B.C.E.), generated a good deal of intellectual ferment that provided the background for such philosophers as Confucius concerned about the decay of values.

Qin Dynasty (256-202 B.C.E.)

By the third century B.C.E., seven major warlord states had emerged. Among these was the Qin Dynasty in the north, which built up a powerful state through sweeping internal reforms and the creation of a powerful army using horse archers modeled after those used by their nomadic enemies. By 221 B.C.E., the Qin ruler, Shih Huang Ti, had replaced the last Zhou emperor, and ruled all of China. In fact, his title, Shih Huang Ti, meant first universal emperor, while his dynasty's name (also spelled Ch'in) came to represent all of the people of the Middle Kingdom which we today still call China.

Shih Huang Ti was a harsh, but efficient ruler who brought China under a single autocratic rule. He lowered taxes and restored canals and irrigation systems. He also redistributed land to the peasants in an attempt to break up the nobles' power. Along these lines he broke up China's old provinces and loyalties and created new ones ruled by non-hereditary governors who could not build their power up in one place over several generations. Shih Huang Ti also created a unified law code, tax system, coinage, and system of weights and measures so that government and commerce could proceed smoothly.

The Qin emperor had numerous building programs, among which were roads and canals to promote trade as well as the swift movement of armies, a huge capital at Hsien Yang where all the most powerful families of the realm were required to move, and a fabulous tomb guarded by 6000 larger than life terra-cotta soldiers in full battle order armed with bronze weapons, chariots, and terra-cotta horses.

However, the most famous and far-reaching of Shih Huang Ti's building projects was the Great Wall built to contain the nomadic horsemen from the north. In fact, previous generations of warlords had built several local walls to protect their realms from the nomads and each other. Shih Huang Ti, in a mere seven years, connected them into one continuous defensive system 25 feet high, 15 feet thick, and stretching some 1850 miles through mountains and deserts. The cost in human lives was staggering, as thousands died from exposure to the elements, hunger, and exhaustion, causing Chinese peasants to call the Great Wall "China's longest cemetery."

Manning the entire wall was beyond the means of even the Chinese. However, it was built more against the nomads' horses than the nomads themselves. As long as the wall was kept in repair and the intermittent forts and towers were manned, the nomads would be held at bay by two factors. First, they lacked siege engines for attacking manned forts. Second, they would not scale the unmanned sections, since that would involve leaving their horses behind. Only when the wall was in disrepair and unmanned during times of weak government and turmoil, could the nomads could break (or bribe their way) into China. Otherwise the Great Wall served its purpose as succeeding Chinese dynasties would repair, modify, and expand it as the real and symbolic boundary between civilization and the nomads.

Shih Huang Ti's reforms may have unified China into one empire and people, but of the heavy burden in taxes and labor needed to support his building projects made him very unpopular. Another source of resentment was the emperor’s refusal to tolerate any dissenting ideas, especially those of the Confucianists who preferred the traditional feudal structure of government to his more impersonal bureaucracy. Therefore, he ordered the burning of all works of philosophy that in any way contradicted his policies. He even had some 460 dissenting scholars executed, supposedly by burying them alive. Although some scholars tried to entrust these works to memory so they could be written down later, there were certainly mistakes in the recopying, and there is no telling how much was lost. This purge also deprived the emperor of good advisors and poisoned the atmosphere at court, making it difficult to create sound policies. Therefore, his death in 210 B.C.E. triggered a number of revolts and civil wars that led to the rapid fall of the Qin Dynasty and the rise of the Han Dynasty.

The Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E.-220 C.E.)

Liu Pang, the founder of the Han Dynasty, found China worn out by civil strife and heavy taxes and also facing threats from the northern nomads. Liu Pang (also known as Kao Tsu) and his successors tackled each of these problems and laid the foundations for one of China's true golden ages. Although the Han reversed the more repressive aspects of the Qin dynasty, they also built upon many of their other policies. In that sense, the Qin and Han dynasties should be viewed together as forming the basis of Chinese imperial power and cultural influence in East Asia.

For one thing, the Han rulers reduced Shih Huang Ti’s more excessive demands by eliminating forced labor, lowering taxes, and restoring the Classics, although the accuracy of that restoration is still in dispute. However, they did uphold the Qin Dynasty’s more enlightened reforms, especially redistribution of land to the peasants, making them much more popular than the Qin and the foundations for one of the high points in Chinese history and civilization.

In government, the Han ended the Qin policy of using non-hereditary governors and reverted to the older practice of using royal family members instead. However, they continued and expanded the Qin use of professional bureaucrats to run the day-to-day machinery of government. This was the result of growing influence of Confucianism at court, since the Han dynasty saw its emphasis on ritual and tradition as a valuable justification and support for their rule. Therefore, it instituted the civil service exams that determined applicants' potential as bureaucrats by testing their knowledge of Confucian teachings, now the official state philosophy. Although modern civil service exams test supposedly more practical skills, such as math and reading, to choose bureaucrats, the idea of hiring government officials on the basis of ability rather than birth or personal connections traces its roots back to the Chinese civil service exams of the Han dynasty. Despite China's varying fortunes, the Chinese civil service was generally the best in the world until the 1800's.

The backbone of the Chinese bureaucracy was a class of scholars known as the civil gentry who would run Chinese government and administration until the early 1900's. Since gaining admission into this class depended on knowledge of Confucianism rather than birth or connections, many middle class families advanced their sons' fortunes in society by investing heavily in their education. Even after the demise of the civil service exam system, this emphasis on education has remained a powerful factor in East Asian societies, helping to account for their high literacy rates and rapid economic development in recent history.

Finally, there was the ever-present threat of the northern nomads. The Han emperors, here also continuing the work started by the Qin, maintained and expanded the Great Wall and a huge army to bring the nomads under control. Although Han armies met frequent defeats, their persistence did establish a semi-civilized buffer zone in the north.

However, especially in times of turmoil, semi-civilized nomads would often prove to be even more dangerous to China, since they combined both their own restless nomadic energies with knowledge of Chinese civilization in order to organize powerful states that could conquer China. But, as always, such invaders would eventually be absorbed by Chinese civilization. As the historian, Fernand Braudel put it, China let in such invaders and then shut the door behind them.

For nearly four centuries, Han reforms and rule provided a strong empire which expanded its political and cultural influence southward into the rice growing regions of Southeast Asia, northward into the nomadic regions, and northeastward into Korea and Manchuria. Internally, the Han provided a period of peace and prosperity that largely resembled the Roman Empire then flourishing at the opposite end of Eurasia. Science and technology flourished, making China the leading culture in those fields for centuries. The invention of paper (made from rags), the sundial, water clocks, and surgery using acupuncture were some of the main accomplishments of this period. New forms of literature, especially, history, poetry, and diaries, were developed.

Buddhism started gaining influence in China at this time despite initial resistance from the Confucianists and government. However it gained popularity and became the final part of the Three Doctrines of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Whereas the three religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam would compete, sometimes violently, for adherents, the Chinese were able to incorporate all of the Three Doctrines into their culture since they fulfilled various needs, Confucianism being a very practical and structured way to run one's daily life and career, Taoism being a more natural way to enjoy life outside of work, and Buddhism being a preparation for what lies beyond this life. As many Chinese saw it, one is Confucianist during the day at work, Taoist in the evening when relaxing, and Buddhist at night when going to bed.

Trade also prospered as never before, both within China and with other cultures. The most renowned example of this foreign trade was the fabled Silk Road that carried silk, furs, cinnamon, iron, and rhubarb westward across Central Asia through any number of middlemen and eventually to Rome. Silk was a luxury in Rome that was literally worth its weight in gold. In order to stretch it out, the Romans wove silk into a very loose gauze-like fabric that the Chinese would hardly have recognized. Interestingly enough, the Romans and Chinese did not meet face to face until 166 C.E. when a Roman envoy finally made it to China. Unfortunately, both civilizations were on the verge of their respective declines, and contact was lost soon afterwards.

As powerful and prosperous as Han China was, it had an inherent weakness, namely that it was based on a huge army and bureaucracy that put a tremendous strain on the economy. This had two main results. First of all, the peasants, who bore the brunt of the taxes, increasingly lost their lands to nobles whose power grew in opposition to the central government. This caused revolts both by oppressed peasants and power hungry nobles. Secondly, as the economy faltered under the strain of heavy taxes, nomadic raids stepped up, which hurt the economy even more, triggering more raids, and so on. Together, these raids and revolts weakened the Han Dynasty, forcing it to increase the army and taxes, and so on. Finally, in 220 C.E., the Han Dynasty fell, ushering in another period of turmoil.

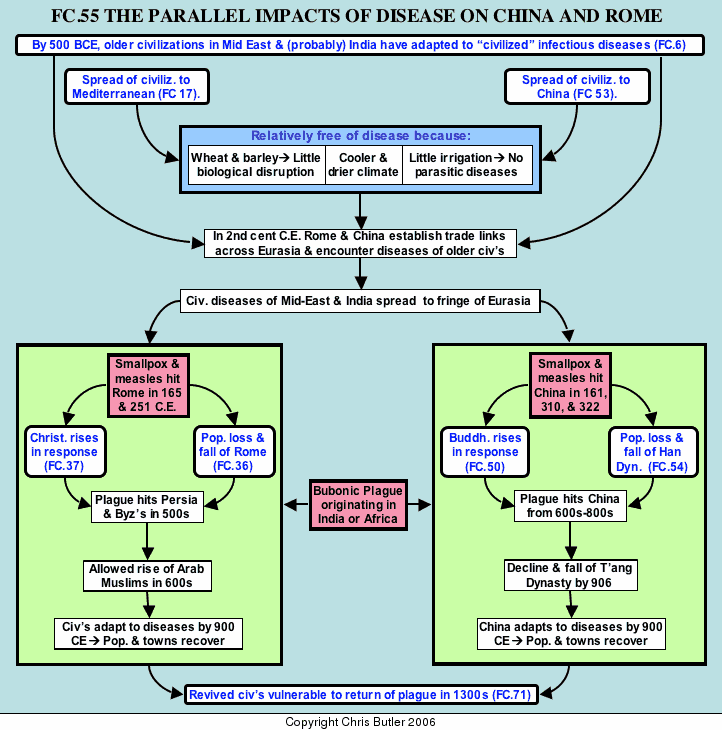

FC55The parallel impacts of disease on Chinese and Roman history

"In the area south of the Yangtse, the land is low and the climate humid; adult males die young"

-- Ssu-ma Ch'ien, father of Ch. historiography (145-87 B.C.):

By 500 B.C.E., the earliest civilizations on the Middle East had expanded their empires to the limits of the Middle East.and a fairly stable balance had been achieved where they had at least partially adapted to the parasitic and infectious diseases of the region and evolved into "childhood diseases" where concentrations of populations allowed them to survive as a chronic, but usually not fatal, nuisance.

However, the newer areas of Eurasia where civilization spread, the Yellow River in China and the Mediterranean in the West, were relatively free of infectious diseases. This was largely because wheat, and barley, the main crops grown there, were native to the regions, thus causing relatively little biological disruption. This contrasted with areas that practiced irrigation for non-native crops, which exposed people to water borne parasitic diseases. Although there was irrigation in the Yellow River area of China, its cooler and drier climate led to considerably fewer problems with parasitic diseases than the earliest hydraulic civilizations encountered. However, when the Chinese spread southward into the Yangtze River region with its hotter and more humid climate, they encountered water and insect borne diseases to which it took centuries for them to adapt.

In the second century C.E , as Rome and China established trade links across Eurasia, they also encountered the older infectious diseases of the older civilizations in between. As a result, these diseases spread to the eastern and western fringes of Eurasia with very similar results.

In the East, small pox and measles, diseases never previously encountered there, hit China in 161, 310, and 322. Such unprecedented disasters led people to question traditional Chinese beliefs and opened the way for the rise of Buddhism. The severe population loss these outbreaks caused also contributed to the fall of the Han Dynasty and several centuries of turmoil, until the revival under the Sui and T’ang Dynasties. However, in the 600s, the eruption of a new disease, arising from India or Africa, bubonic plague, caused another huge loss of life and probably contributed to the decline and fall of the T’ang Dynasty by 906. After 900, the Chinese had adapted somewhat to this scourge, and China saw its population and towns expand rapidly under the Sung Dynasty.

In the West, the Roman Empire also suffered the initial onset of smallpox and measles in 165 and 251, helping lead to a period of anarchy in the third century and the eventual fall of the Empire by 500. And, like in China, people questioned the old pagan religions, leading the growing popularity and eventual triumph of Christianity. Then, as population and prosperity were recovering, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean, bubonic plague hit in the 500s, allowing the sudden rise of the Arab Muslims in the 600s. By 900, the plague had also subsided in the Mediterranean and Western Europe, allowing the revival of towns and trade.

Unfortunately, these newly revived cities with their concentrations of populations were especially vulnerable to onset of a new strain of the plague in the 1300s, triggering possibly the greatest demographic disaster in history.

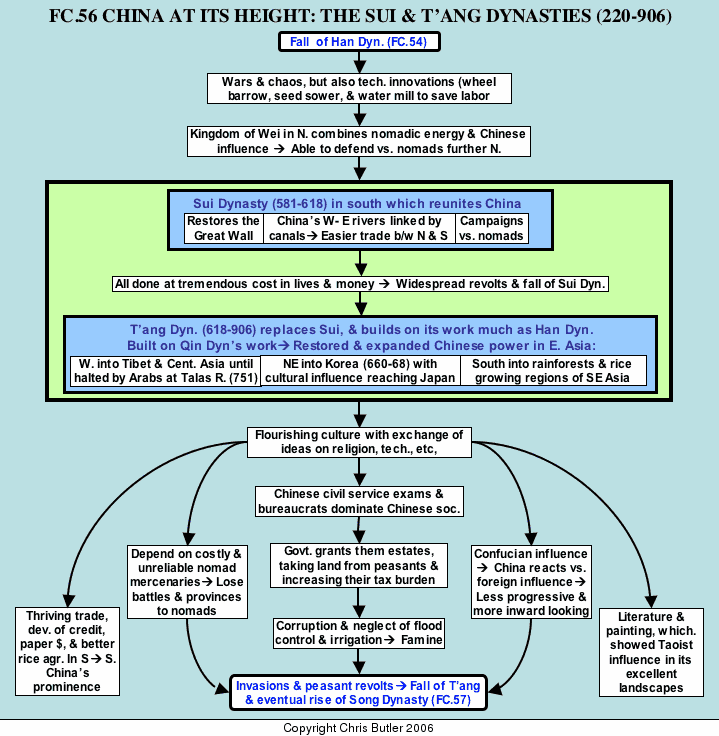

FC56The Sui and T'ang dynasties (220-906 CE)

The Six Dynasties Period (220-581 C.E.)

The fall of the Han Dynasty brought in a period of political anarchy known as the Six Dynasties Period. During this time, China was divided into three main kingdoms: Wei in the north where wheat and millet were grown and nomadic pressure was most intense, Shu Han in the west, and Wu in the rice growing regions of the south-east where many Chinese fled to escape the chaos in the north. The kingdom of Wei, which was situated between other nomads in the north and the Chinese in the south, was the first kingdom to successfully combine nomadic culture and Chinese influence. As a result, it was more organized than its nomadic neighbors while still keeping its nomadic energy, making it able to protect Chinese civilization in the south from the wilder nomads in the north. In addition, there were several technological innovations to compensate for labor shortages at this time: the wheel barrow, watermill, and a primitive seed-sower, all of which allowed Chinese culture to prosper more than the Germanic heirs of Rome were able to at this time in Western Europe.

The Sui Dynasty (581-618)

After several centuries of various dynasties competing for power, the Sui Dynasty reunited China. Much as the Qin Dynasty had laid the foundations for the Han Dynasty's greatness, the Sui Dynasty, despite the shortness of its reign, laid the foundations for the T'ang Dynasty's accomplishments through several endeavors. The Sui restored the Great Wall and mounted a number of huge expeditions against the northern nomads. They helped restore foreign trade, especially along the Silk Road. Likewise, they restored internal trade by connecting China's main rivers, which all run from west to east, with a north-south channel known as the Grand Canal. As a result, trade and travel between North and South China became much easier. Unfortunately, much as with the Qin Dynasty, these military expeditions and building projects involved a tremendous cost in lives and money. This triggered widespread revolts and the overthrow of the Sui Dynasty by a new dynasty, the T'ang, which would take Chinese civilization and imperial power to new heights.

The T'ang Dynasty (618-906)

The T’ang were a military family from the wild northwest frontier and were especially skilled in the use of cavalry. The T'ang, themselves devoted horsemen, bred thousands of horses for their cavalry and imported polo from Persia, which even ladies from court played. Using their cavalry along with large numbers of allied nomadic cavalry and peasant infantry, the T'ang could deal with the Northern nomads and expand Chinese rule in several directions. After stubborn resistance, they conquered Korea in 668 and saw Chinese culture take deeper root in Japan. The T'ang also conquered North Vietnam, then known as Annan (modern Annam), meaning "pacify the South". They drove westward against Turkish tribes in Central Asia, established their power and influence in Tibet, Afghanistan, and India. In 661, Chinese forces even briefly restored the last Sassanid Persian ruler, Peroz, against the rising tide of Arab Muslim conquest. When the Persian king was finally overthrown for good, he found refuge in the Chinese court. Later, the Arabs would defeat a Chinese army at the Talas River in 751 and bring T'ang expansion to a halt.

The unprecedented foreign influences that empire brought into T'ang China were welcomed with a new open-mindedness. Foreign fashions, music, cuisine, art, and religious influences from Central Asia, India, and Persia found favor at the court in China's capital, Ch'ang-an. Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism all found their way to China, while Nestorian Christians, who were branded heretics and exiled by Rome in the fifth century, gained converts across Central Asia and were granted toleration in China as well. Later on, religious persecution (841-45) would eliminate Christianity, although the other religions would survive. Buddhism especially became absorbed into the fabric of Chinese religions, assuming a place alongside Taoism and Confucianism as one of the Three Doctrines which complemented one another rather than acting as competition against each other, as happened between Judaism, Christianity and Islam further west.

Cultural influence worked both ways, however, as Chinese culture and technology spread to Korea, Japan, and even the tribes in Central Asia. One example of this influence was the spread of rag paper, which was invented, in the early Christian era. Most likely it reached the Muslim world as a result of the Battle of the Talas River in 751, when the victorious Arabs captured Chinese technicians skilled in its manufacture. Eventually, it would spread to Western Europe where it would be combined with another Chinese invention, block printing to create the printing press, one of the most dynamic and important inventions in history. While it is a European invention, its roots lie deep within Chinese history.

Drawing upon these foreign influences and combining them with its own dynamic energy, Chinese culture prospered and flourished under the T'ang Dynasty in three areas: the economy, government, and culture. China's economy prospered largely through trade that thrived both within China and with the outside world. Foreign trade prospered, especially along the Silk Road that maintained commerce and contact with other cultures further west. Although trade certainly thrived, little is known about it, since so much was controlled as government monopolies (e.g., salt, wine, iron, and tea) or interpreted as "tribute" from foreign lands and reciprocal "gifts" going back out. China’s internal prosperity was especially reflected in its cities, which were the largest and most populous in the world. Foremost among these cities was the capital, Ch'ang-an with a population of some 2,000,000 people. It was laid out in a rectangular grid five miles wide by six miles long and facing the cardinal directions in accordance with the Chinese concept of the cosmic plan.

One of these monopolies had a profound influence on the history of finance. In the early 800's, merchants selling tea to the government received government notes worth the hard cash value of the tea. These exchange notes, known as "flying money," proved to be popular, since they eliminated the need for carrying heavy coins. The use of credit slips soon spread among Chinese merchants and moneychangers and eventually westward to the Arab world, where they were known as sakk, and eventually to Western Europe where the term sakk became check. Meanwhile, in 1024, the Chinese government would expand the use of credit slips by issuing the first true paper currency in history.

Chinese agriculture also prospered under the T'ang Dynasty. For one thing, careful censuses and an equitable system of distributing land and the tax burden among the peasants strived to ensure their prosperity. Second, the system of canals connecting China's rivers meant that relief could be brought to famine stricken areas. Finally, agriculture saw particular progress in the South where new strains of rice and better farming techniques dramatically increased crop yields with resulting population growth. Eventually, under the next major dynasty, the Song, the balance of power and population would shift from the North, where Chinese civilization first evolved, to the South.

Power and prosperity also brought a flowering of the arts in China. Buddhism, coming from India, had an especially profound influence on Chinese sculpture. However, it was in poetry and painting that one could especially see the Chinese genius at work. Both poetry and painting showed a typically Taoist love of nature through their portrayals of flowers, mountains, rivers, and clouds, but rarely the sea, since the Chinese were traditionally a land loving people.

Another development was the further improvement of the civil service exam system and the emergence of the official gentry who had passed these exams as the main bureaucrats of China. This system had been used by the Han Dynasty, but only in conjunction with the older patronage system favoring nobles and political connections. Now the exam alone determined who attained bureaucratic positions in China. However, since education was expensive, only the rich could afford to train one son per family to take the exam. As a result, the officials became a virtually hereditary class. The training and exam stressed Confucianist classics more than mathematics and law, the purpose being to cultivate wisdom and morality in China's officials. In the centuries to come, China's stability and resilience would largely be based on these official gentry.

In 690, the official gentry's fortunes rose further when the only woman to rule China in her own right, the empress Wu, seized power. Her fear of the T'ang military aristocracy in the Northwest probably spurred her to complete the transformation of the civil service in order to favor a completely civilian class of bureaucrats whose status was based on merit. However, their rise to power meant a corresponding decline of the military nobles, which eventually would weaken China's defenses and help lead to the decline of the T'ang Dynasty.

Fall of the T'ang Dynasty

Several factors led to the fall of the T'ang Dynasty, three of them related to the triumph of the official gentry and the civil service system. For one thing, the government granted the gentry estates, thus taking land from the peasants and increasing their tax burden. This, along with a series of famines partly caused by government corruption and neglect of flood control and irrigation systems, triggered peasant revolts. Secondly, the gentry's dominance of the government caused the emperors to ignore the army and start relying on nomadic mercenaries who were more expensive and much less reliable than native recruits. As a result, T'ang armies suffered a number of defeats, notably at the Talas River against the Arabs in 751, making Islam rather than Buddhism the dominant religion in Central Asia. The weakened army invited invasions from without and revolts from within. Finally, the rise of the official gentry unleashed a Confucianist reaction against foreign influences in China. From now on, China would be more inward looking, sometimes blocking out new ideas that could have been of great use.

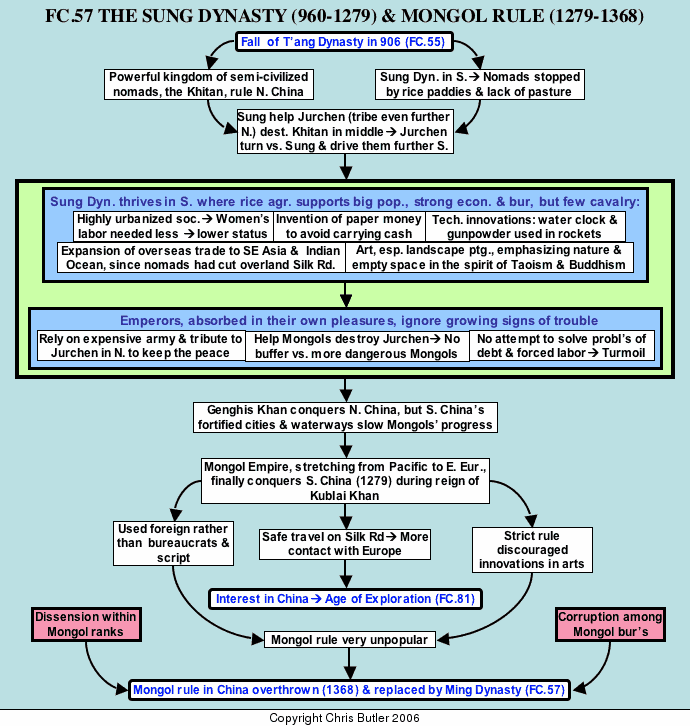

FC57The Sung & Mongol dynasties (906-1368)

The Sung Dynasty (960-1279) . The fall of the T'ang Dynasty ushered in a brief period of chaos referred to as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (906-960). Despite this turmoil, Chinese civilization maintained itself, especially in the South where many people fled to avoid the northern nomads. Out of this chaos, two new kingdoms emerged.

First of all, the semi-nomadic Khitan built a powerful realm in the North that even encompassed the Great Wall. What made the Khitan so dangerous was that they had partially absorbed Chinese culture, thus fusing their nomadic energy with Chinese sophistication. In the middle Ages, many people mistook the Khitan as the Chinese and referred to China as Cathay (land of the Khitan). Throughout this period, the Khitan kept up pressure against a new Chinese dynasty, the Sung, who brought all but the northernmost provinces and the Great Wall under their control. Sung government was efficient, maintaining the irrigation and flood control projects to ensure economic prosperity. The Sung also weakened the influence of the military in favor of the bureaucratic gentry who were hostile toward the military. This and the lack of pasture for good cavalry horses in the south caused the Sung to pay less attention to maintaining a good native-born military and to rely more heavily on expensive mercenaries and paying tribute to keep their northern enemies at bay. Therefore, when the Sung did finally attack the Khitan, they were no match for their mobile horse archers who forced them onto the defensive.

In the early twelfth century, the Sung called in another nomadic people from further north, the Jurchen ruled by the Chin dynasty, to destroy the Khitan realm. Unfortunately, the Jurchen, proving less civilized and more dangerous than the Khitan, turned against the Sung and forced them even further south after 1126. One advantage of ruling in the South was that its numerous waterways and lack of pasture impeded invasions by any nomadic cavalry, thus keeping Sung China relatively secure.

Despite these pressures, the Southern Sung Dynasty (1126-1279) still flourished with a thriving economy based largely on rice agriculture. This helped create a more urban society, with five Chinese cities reaching populations of one million. Ironically, the more comfortable urban culture hurt the status of Chinese women, since their labor, which was so vital on the farm, was not needed nearly as much in town.

Economically, the Chinese were the first to use paper money, getting the idea from the bills of credit used under the T'ang Dynasty. The advantage of paper money was that it saved the burden of transporting heavy cash (which was all in copper coins), especially taxes, long distances. As its nickname, "flying money", implies, paper money was easy to print (thanks to block printing also invented by the Chinese), and its overuse later on triggered inflation. Even such measures as scenting it with perfume or sewing in threads of silk failed to solve this problem that still bothers governments today.

The Chinese economy, largely blocked from overland trade to the northwest, saw rapid expansion through the vigorous pursuit of sea-borne trade to South-east Asia and into the Indian Ocean. Unlike the northern Chinese, who preferred to remain on land, the Chinese in the South were more at ease with the sea. (Even today, a preponderance of Chinese immigrants to the United States originates from the southern parts of China.) Several technological innovations helped the Chinese in their maritime ventures. First of all there was the Chinese sailing ship, the junk, which was faster and several times larger than any European ships then sailing. It also had a sternpost rudder and separate watertight compartments, something European sailing ships would not be able to match until the 1800's. Another invention brought back by Arab traders to Europe that would be vital to later European explorations was the compass. For centuries, the Chinese had used the compass for divination and fortune telling before applying it to navigation. Chinese compasses pointed south, since that was where spring winds came from and was considered the most important direction on Chinese maps.

By 1200, the Chinese had replaced the Arabs as the dominant commercial power in the Indian Ocean, trading books, paintings, and porcelain along with silk, tin and lead. All this trade brought large numbers of foreign traders to China, many of whom settled down in self-contained communities where they could live under their own laws. One of the most prominent of these was a Jewish community that survived into the 1800's.

Two other Chinese inventions deserve mention here: the water-powered clock and gunpowder. The Chinese clock was powered through a complex system of gears and escapements. In addition to keeping daily time, it also tracked celestial time and the movement of the sun, moon, and planets for astrological purposes so the emperor would know the best time to embark upon various projects and ventures. Although it was an imperial monopoly, the clock made its way to Europe where it would be adapted in the later Middle Ages to tracking daily time. Eventually, the clock would heavily influence Western Civilization's concept of time by breaking it into precise and discrete units that still regiment our lives today.

Gunpowder, according to legend, was the accidental result of a Taoist alchemical experiment for replacing salt with salt petre (the active ingredient in gunpowder). Contrary to popular belief, the Chinese did use gunpowder for military purposes in the form of rockets and firing projectiles out of bamboo and metal tubes. Most likely, it made its way westward to Europe thanks to the Mongol conquest of China in the 1200's. Eventually, the Chinese invention of gunpowder would be instrumental in the rise of the nation state in Western Europe and Europe's colonial dominance of the globe in the late 1800's and early 1900'.

The arts, in particular painting, flourished under the Sung Dynasty. Chinese painting heavily reflected Buddhist and Taoist values by emphasizing nature and even empty space. Some painters were so brilliant that they could create a painting that had to be viewed from multiple perspectives. This contrasted greatly with European painting, which put more emphasis on humans as the center of attention.

The Mongol Empire (1279-1368)

Although the overland routes to the West were mostly cut off, the Sung Dynasty did see some trade, largely in the form of superior iron weapons, going north through the semi-civilized Jurchen to the much more dangerous Mongol tribes further north. In the late 1100's, the most remarkable nomadic leader of all time, Genghis Khan (1167-1227), combined the use of Chinese weapons, Mongol fierceness, and his own genius for organization and generalship to launch the conquest of the most far-flung empire in history. He succeeded in conquering northern China, but the large fortified cities, lack of pasture for the Mongol horses, and the vast network of waterways obstructing the way kept him from conquering the Sung Dynasty in the South. Therefore, he left it to his successors to complete the conquest, which his grandson, Kublai Khan, did in 1279. By that time, Mongol conquests spread from the Pacific to Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Although there were several virtually independent Mongol khanates, Kublai Khan was recognized, at least in theory, as the supreme ruler over all.

Mongol rule led to several changes in China and Asia. For one thing, the Mongols protected safe travel across Asia and reopened trade along the Silk Road. Because of this, Western Europe, then recovering from the Dark Ages, re-established contact with China, allowing numerous traders and missionaries to make their way there. Among these travelers was Marco Polo, whose account of his travels and the wonders of the East sparked a growing interest in China which would help stimulate the Age of Exploration some two centuries later.

The Mongols ruled with a brutal efficiency that not only discouraged any criticism of them, but also discouraged innovations in the arts. Among the Mongols' ruling policies was replacing the civil service exam system with the use of non-Chinese governors and officials and even a foreign script. However, in the 1300’s, the civil service exam was restored as the Mongols in turn succumbed to the influence of Chinese civilization. Mongol rule was especially unpopular with the Chinese, who looked for any opportunity to revolt. Two factors helped provide that opportunity, dissension within the Mongol ranks and corruption among their bureaucrats. Finally, in 1368, the Chinese overthrew Mongol rule and established a new dynasty, the Ming, which would once again restore Chinese power and wealth.

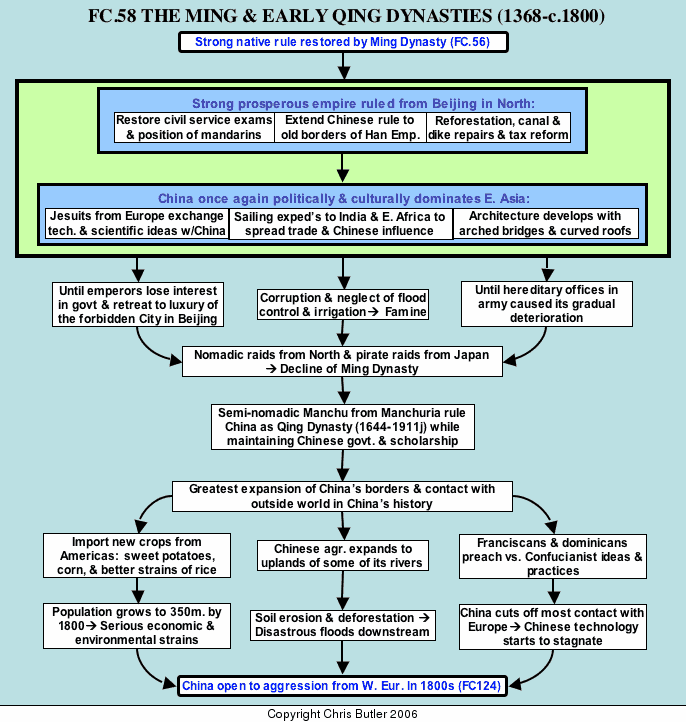

FC58The Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-c.1800)

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

The expulsion of the Mongols from China in 1368 ushered in a new period of peace and prosperity for China under the Ming ("brilliant") Dynasty. The early Ming emperors revived Chinese power and wealth through their foreign, governmental, and economic policies. In the realm of foreign policy, several strong emperors aggressively extended Chinese power to the old borders of the Han Empire. Not surprisingly, the Ming Dynasty was especially concerned with the threat of the northern nomads who had so recently humiliated China. Therefore, they put forth a tremendous effort to subdue the nomads (with very limited success) and partially restored the Great Wall. The fortifications around the first capital, Nanjing, were 60 feet high and extended in a perimeter 20 miles long, the most massive urban fortifications in the world In 1421, the Ming moved the capital to Beijing, only 40 miles from the northern frontier in order to keep a better eye on nomadic movements. Not only did this endanger the capital, since it was so close to the nomads, it also removed the government from contact with and understanding of the more economically vibrant South. As it was, the nomads posed no real serious threat to China during most of the Ming Dynasty's rule.

Beijing itself became a magnificent city with 40-foot high walls around a perimeter of 14 miles. Central to the capital was the emperor's palace complex, known as the Forbidden City. Unlike Western architecture, which reaches ever skyward away from earth, as seen in Gothic cathedrals and skyscrapers, Chinese architecture aims for a more balanced and harmonious effect in the true Taoist spirit. The Forbidden City especially shows this, being spread out on a broad horizontal plane under the overarching dome of the blue sky, which counterbalances the effect of the high roofs of many of the government buildings and palaces. The overall effect is one of horizontal stability, emphasizing the permanence of the regime of the Son of Heaven (Chinese emperor).

The Ming reversed the unpopular policies of the Mongols and reinstated the system of civil service exams for selecting officials, thus restoring the Mandarins to prominence in Chinese society. They also retained the other features of government used by previous dynasties, such as the Six Ministries and the Censorate. The Censorate was largely concerned with preventing corruption and abuses by sending traveling censors to the provinces to hear complaints and investigate the conduct of local magistrates. Unfortunately, many censors were young officials being asked to report against senior officials who could seriously damage their careers later on. Since the censors had little protection against such reprisals, they often shrank from doing their jobs properly. However, the overall effect of Ming policies was to provide fair and efficient, though strict, government.

Ming economic policies similarly provided for China's prosperity during this period. Dikes and canals were repaired, while extensive land reclamation program was instituted, since some regions of China were totally depopulated from earlier Mongol depredations and neglect. The government offered tax exemptions lasting several years to any peasants who moved into the ruined areas, a policy which effectively revived much of China. Another policy was to encourage extensive reforestation, probably for shipbuilding purposes, although palm, mulberry, and lacquer trees were also planted for other economic purposes.

As a result of the Ming Dynasty's policies, China was again a strong and prosperous empire, making it the dominant political and cultural power in East Asia. China's cultural vibrancy can be seen in several aspects of the Ming era. For one thing, architecture flourished, as the Chinese constructed arched bridges and tall pagodas with graceful curved roofs. As stated above, the setting of these buildings in broad horizontal planes provided a more balanced effect than the lofty spires of cathedrals one found in Europe at that time.

Chinese science and technology at this time was largely bound up with newcomers from the West. The expulsion of the Mongols in 1368 effectively cut China off from the West for nearly two centuries. In fact, Columbus was still looking for the Mongols in 1492, since Europe had not received word of their fall over a century after its occurrence. However, in the 1500's, the Portuguese and then the Spanish arrived in China by sea. Most of China's contact with the West at this time was through the Jesuits who skillfully presented Christianity in Confucian terms in order to gain entrance into China and win converts to their faith. Ironically, the Jesuit leader, Matteo Ricci, won court favor by presenting the emperor with a wind-up clock, which, of course, was ultimately derived from the Chinese water clock. (He kept in their good graces by keeping the key, so he would be summoned to court each week to rewind the clock.) Over time, the Jesuits provided the Chinese with a good idea of the state of Western science and technology, especially in the areas of mathematics, cartography, astronomy, and artillery. Europe learned a great deal from China as well, such as the idea for its first suspension bridge, built in Austria in 1741, over 1000 years after the first such bridge had been built in China.

Extensive maritime expeditions into Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and as far as East Africa and Arabia, were another feature of the early Ming period. Between 1405 and 1433, no less than seven major expeditions were launched under the command of the admiral, Zheng He (1371-c.1434). Some of Zheng He's expeditions comprised over 25,000 men sailing in ships that were 400 feet long, many times larger than anything Europe, just then embarking on its age of exploration, could put into the water. The purpose of these expeditions is not entirely clear, probably being more to display Chinese power and influence than cultivate trade, although profitable trade was certainly carried on, especially in fine porcelain, which we today still call china. Then, in 1433, the expeditions suddenly ended, once again for vague reasons. One idea is that the mandarins, resentful of the profits made by the middle class merchants running these expeditions, pressured the emperor to end them. Whatever the reasons, it is tantalizing to think of what might have happened if these expeditions had continued, possibly with China discovering a route to Europe. As it was, Europe was left to find those routes and eventually dominate the globe.

The end of these expeditions had other far-reaching results for China, since they deprived the government of vital trade revenues. This, combined with two other factors, led to the decline and fall of the Ming Dynasty. First of all, the later Ming emperors lost interest in government, retreating to the comfort and pleasures of the Forbidden City and allowing abuses and corruption to multiply in the provinces. At the same time, the practice of making military offices hereditary led to the gradual deterioration of the army. Together, these factors weakened China and encouraged a growing number of peasant rebellions, attacks by nomads in the North, and raids from pirates in Japanese and Chinese ports. In 1644, another northern people, the Manzhou from Manchuria, replaced the Ming Dynasty and founded a foreign, and China's last, dynasty.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

The Qing Dynasty founded by the Manzhou, although of nomadic origin, had absorbed much of Chinese culture and did everything it could to portray itself as a legitimately Chinese dynasty. As a result, the emperors revived the civil service exams and other governmental institutions, restored the mandarins to the levels of prestige they had enjoyed before Mongol rule, and maintained interest in classical scholarship. (However, the Manzhou also outlawed the crippling practice of binding Chinese women's feet and forced the Chinese peasants to shave their heads except for wearing Manchurian-style pigtails.) Militarily, the Manzhou extended China's borders to their greatest extent ever, encompassing Manchuria, Mongolia, Siankiang, Tibet, Korea, Burma, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

All this time, contact with the West continued. However, in the long run, it caused problems for China in two very different ways. For one thing, several new crops, such as corn, sweet potatoes, and better strains of rice, were imported, thus making China's agriculture much more productive. In the short run this was good. But, in the long run, these new crops and improved transport of food along China's canals and waterways, both of which allowed specialized cash crops suited to local soils, triggered a population explosion that pushed China's population to nearly 400,000,000 by 1800. At the same time, China's agriculture was expanding into Manchuria, which held the upland and drainage areas of some of China's rivers. Extensive farming here caused soil erosion and deforestation that triggered disastrous flooding downstream. These floods plus overpopulation put severe strains on China's ability to feed so many people and seriously weakened it.

The second problem had to do with religion. As we have seen, the Jesuits were allowed to preach Christianity in China, because they presented their religion in Confucian terms and were tolerant of Confucian practices. All that changed when Franciscan and Dominican priests arrived and started behaving in a much less tolerant manner than the Jesuits, condemning, among other things, the venerated Chinese custom of ancestor worship. Also, unlike the Jesuits, who concentrated on the educated ruling classes, the Franciscans and Dominicans preached more to the masses, which made Chinese authorities suspicious and resulted in a crackdown on Christianity in China (although the Jesuits still maintained some status at court) and a curtailment of trade with the West in the 1700's.

Unfortunately for China, Europe's power and interest in Chinese goods, especially tea, were growing beyond China's ability to hold these western "barbarians" back from its gates. The result would be a century of humiliation at the hands of the West and a revolution that would at once transform China and maintain its unique culture and integrity as a nation.