FC103Balance of Power Politics in the Age of Reason (1715-1789)

Dogs! Do you want to live forever?— Frederick the Great, to his troops in the heat of battle.

Introduction

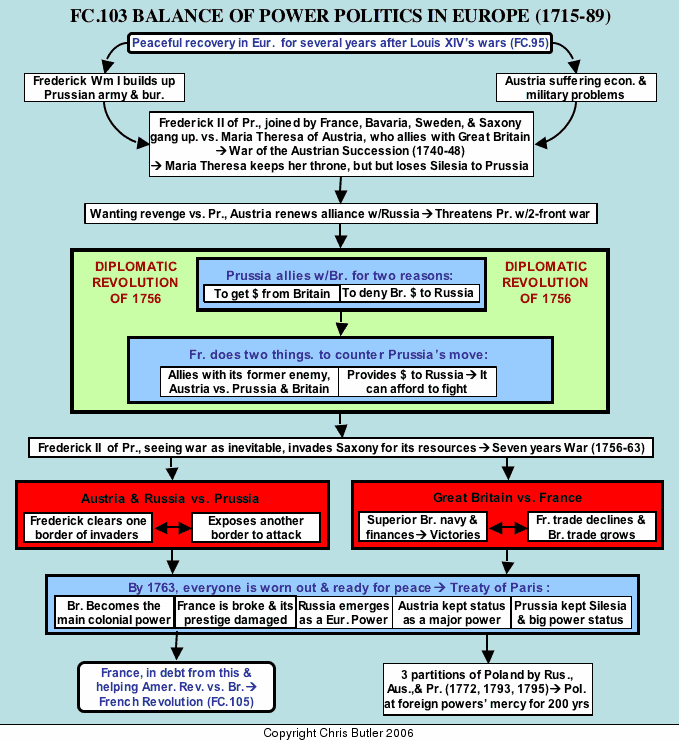

The period from 1715-1789 was one of transition between the religious wars of the 1500's and early 1600's and the wars of nationalism and democracy starting with the French Revolution. This was also the era of balance of power politics where Europe operated as an integrated system, so that one state's actions would trigger reactions from all the other states. As a result, it was hard for one state to gain an overwhelming position in Europe without everyone else, in particular Britain, ganging up to restore the balance. Finally, it was a period of intense competition between European states, a competition that would launch Europe into the two bloodiest centuries in all human history.

Diplomatic maneuvering (1715-1740)

The death of Louis XIV in 1715 ended the bloodiest and most exhausting period of warfare up to that point in European history. The scale of bloodshed and expenditure was so massive that it would take several years before Europe would be ready for another major war. However, mutual distrust kept the various powers eyeing each other suspiciously and constantly maneuvering to maintain a stable or superior position in case war did break out. Spain and Austria conspired to take Gibraltar from England, causing Britain and France to ally to stop this plot. Britain, Austria, and Holland signed the Barrier Treaty in 1718, by which Austria got the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium) in return for manning the barrier fortresses against French aggression. Because of this maneuvering (or maybe in spite of it) peace ruled over most of Europe for nearly two decades.

The first major disturbance was the War of the Polish Succession (1733-39). The death of the Polish king led to rival claims by French and Austrian candidates, and these claims led to war. Austria and its ally, Russia, being closer to Poland, emerged victorious over France and Spain. The only compensation was that the Spanish Bourbons got control of Southern Italy and Sicily. The War of Polish Succession symbolized the growing importance of Eastern and Central Europe in diplomatic affairs. In fact, events surrounding two of these states, Prussia and Austria, would dominate European affairs for much of the eighteenth century.

The rise of Prussia

Since the late 1600's, Prussia had been quietly but steadily gaining strength. Under Frederick William the Great Elector (1640-88) and his grandson, Frederick William I (1713-40), Prussia evolved from a small war ravaged principality to a highly centralized independent kingdom. The two pillars of Prussian strength were a highly disciplined and efficient army and bureaucracy. Prussia was a poor country, and Frederick William I did a masterful job of making the most from the least. He did this through a combination of intense economizing and severe discipline and regimentation of virtually every aspect of Prussian society. History has seen few skinflints of Frederick William I's caliber. He cut his bureaucracy in half, cut the salaries of the remaining civil servants in half, dismissed most of his palace staff, sold much of his furniture and crown jewels, and even forcibly put tramps to work. But he expected no more of his subjects than he did of himself as the first servant of the state, probably a legacy of his Calvinist upbringing.

Frederick William's main expense was the army, which is not surprising when one considers Prussia was surrounded by Austria, Russia, and France, all with large armies of at least 90,000 men. By his death in 1740, Prussia’s army numbered some 80,000 men. Frederick William's pride and joy was his regiment of grenadiers, all of them over six feet tall (a remarkable height back then). His friends would give him any six-foot tall recruits they could find, while he kidnapped most of the rest. In spite of this military buildup, Frederick William I followed a peaceful foreign policy and left his son, Frederick II, both a large army and full treasury.

Frederick II presents a fascinating contrast to his father. While the old king detested anything that suggested France and culture, his son treasured those very things. This made Frederick's childhood very difficult. On the one hand, he was required to wear a military uniform and live the life of an officer. On the other hand, he took every possible chance to learn music, speak French, and curl his hair and dress in French fashion. This infuriated the king who often beat his son in fits of rage. The king's chronic illness did not help his temper. Neither did Frederick's tendency to tease his father and see how far he could push him. At one point, Frederick tried to escape from Prussia, was captured, court-martialled, condemned to death, and finally released after a lengthy imprisonment. It is a wonder that one of them did not kill the other. However, when Frederick William I died, father and son were reconciled. It is interesting to see how similar to and different from his father Frederick II would turn out to be as king.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48)

Frederick's eyes were turned toward the rich province of Silesia, then under Hapsburg rule. The timing could not have been better for Prussia. Austria was in pitiful shape to fight a war, having just lost a disastrous struggle with the Ottoman Turks. Its generals and ministers were old men past their prime, while the administration was full of corruption and confusion. And to make matters worse, the old emperor, Charles VI had just died, leaving only a young woman, Maria Theresa, to succeed him. Charles had gotten most of Europe's rulers to sign the Pragmatic Sanction, a document recognizing Maria Theresa as the lawful heiress. But many questioned the legality of Maria and her husband taking the throne, and set up the elector of Bavaria as an alternate candidate. This was the situation for the unfortunate Maria Theresa (who was also pregnant) when Frederick invaded Silesia.

However, as Frederick William I had warned the young Frederick, wars were generally much harder to end than start, and this one did not stop at Silesia. France, Spain, Bavaria, and Saxony all joined Prussia, hoping to pick Austria clean. Austria's ally, Russia, was neutralized when Sweden joined the other side against it and Austria. That left Britain, who was already involved in a war with Spain over control of the West Indies trade. Britain, which generally tried to maintain the balance of power and its trade, backed Austria. Unfortunately for Austria, Britain had a small army and was mainly concerned with defending George II's principality of Hanover from neighboring Prussia. As if Frederick William I had been a prophet, a simple move into Silesia had triggered what amounted to a global conflict, with fighting in India and the American colonies as well as Europe.

Mollwitz, the first battle of the War of the Austrian Succession, was a bit embarrassing for Frederick. His army won, but not until he had run prematurely from the field. After that, however, he showed a flair for brilliant generalship and decisive movements that were unequalled until Napoleon some fifty years later. Frederick's victory at Mollwitz left him with Lower Silesia and left Maria Theresa, who had just given birth to a son, somewhat destitute. However, the young queen showed she had some spirit and fight of her own. She rallied the Hungarian nobles to her side, raised an army, and secured an alliance with England. Next, she made a secret truce with Frederick, giving him Lower Silesia if he would drop out of the war. Then, she surprised everyone by invading Bavaria and throwing her enemies, now without Frederick, off balance.

With Austria's fortunes restored, the war dragged on for eight more years. Frederick would occasionally re-enter the war, revive his allies with his brilliant leadership, and then be bought off with more of Silesia. At last, bloodshed and exhaustion led to the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748. Frederick kept Silesia, while Maria Theresa had survived and saved the rest of her empire. However, she was burning for revenge against Frederick.

The "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756

The first thing Maria Theresa needed to do was reorganize the Hapsburg Empire. Therefore, she centralized the government, reorganized finances, and built up the army. Next, she set about looking for allies to help her gang up on Frederick. First, she renewed her alliance with Russia, thus securing her eastern flank and endangering Prussia's at the same time.

In this she was helped by Prussia's own position and actions. The Austro-Russian alliance already threatened Frederick with a two front war. If he were also attacked from the west and faced a three front war, that would be disastrous. His choice for allies lay between France and Britain. France, his traditional ally was slow moving and reluctant to fight another war. England, on the other hand, threatened him with its Hanoverian lands on his western border, and had signed a treaty agreeing to pay for Russian armies. By secretly allying with Britain, Frederick felt he was neutralizing the threats to both his western and eastern borders, since Britain would now guard, not threaten, his western borders, and subsidize his armies, not Russia's.

Frederick felt that Russia could not fight without British money. He also felt France would not mind his alliance with Britain to keep the balance of power in Germany. He was wrong on both accounts. Louis XV was furious about Frederick making this treaty with Britain without consulting France. As a result, France allied with Austria and agreed to finance Russia's war effort. This ended 250 years of hostility between France and Austria and brought about a virtual diplomatic revolution in how the powers in Europe were aligned. Frederick, finding himself surrounded by enemies, took the initiative and invaded Saxony. The Seven Years War had begun. Now it was Frederick's turn to prove himself in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Seven Years War (1756-63)

was actually two conflicts combined into one giant war. In addition to the continental war of Prussia against Austria, Russia, and France, there was also the struggle for colonial empire between Britain and France. The war assumed global dimensions, extending from Europe to North America, the West Indies, Africa, India, and the Philippines.Prussia's struggle was especially desperate. Frederick, faced with a three front war, was forced to race from one frontier to the next in order to prevent his enemies from combining in overwhelming force. Even then, he still was always outnumbered. Frederick's oblique formation, where he stacked one flank to crush the opposing enemy flank and roll it up, worked time and again to save the day for Prussia. After two brilliant Prussian victories in 1757, Britain came to the rescue with troops to guard Hanover and money to pay for the Prussian army, thus neutralizing the French war effort on the continent.

Even with France out of the picture, the war against Austria and Russia raged year after year and fell into a sort of vicious cycle where Frederick would clear one frontier of enemies. Meanwhile, another enemy would invade Prussia elsewhere, forcing Frederick to rush there to expel this new threat. However, this only exposed another frontier to invasion, and the cycle went on. Against such odds, Frederick lost as many battles as he won. However, his iron will and determination to save Prussia gave him the strength to bounce back, gather a new army, and drive back each new invasion. The Seven Years War became something of a patriotic struggle for the Prussian people, who were called on in greater numbers to defend their homeland. Junkers (nobles) only 14 or 15 years of age rushed to enlist, as did many peasants. The civil service carried on throughout much of the war without pay. The heroic example of Frederick inspired many Germans outside of Prussia to praise him as the first German hero within memory able to defeat French armies. Even French philosophes sang his praises.

But the grim business of war dragged on and on. From Frederick's point of view, this was a war of attrition and exhaustion. If he could hang on long enough and inflict enough casualties, his enemies would tire of the war and go home. As luck would have it, the Tsarina Elizabeth died in 1762. Her successor, Paul, was an ardent admirer of Frederick. Not only did he abandon Austria, but also he offered Russian troops to help Frederick. But Paul was soon murdered by his wife, Catherine, who ascended the throne and pulled Russia completely out of the war. This left only Austria and Prussia, who were both exhausted by the war.

Meanwhile, Britain was striving to build a colonial empire and eliminate French competition. Part of its strategy was to protect Hanover in order to keep Frederick in the war and divert French men and money away from the colonial wars. The colonial struggle took place over North America (known as the French and Indian Wars), the West Indies, India, and slave stations on the African coast. In each case, British financial and naval superiority proved decisive, cutting French troops off from home support while bringing British colonial armies overwhelming reinforcements. The resulting British victories cut French colonial trade by nearly 90% while British foreign trade actually increased. This both deprived France of the means to carry on the colonial war and gave Britain added resources for it, which led to more British victories, more British money, and so on.

In 1762, Spain suddenly joined France's side. By this time, the British war machine was in high gear under the capable leadership of Prime Minister, William Pitt. Therefore, British forces easily crushed the Spanish and took Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Phlippines.

By the end of 1762, both sides were ready for peace. The resulting Treaty of Paris in 1763 was a victory for Prussia and Britain. Prussia, while getting no new lands, kept Silesia and confirmed its position as a major power. Britain stripped France of Canada and most of its Indian possessions, and emerged as the dominant colonial power in the world. Although Russia gained no new lands, it emerged as an even greater European power.

The Partitions of Poland

The Treaty of Paris had effects in both Eastern and Western Europe. In the East, the emergence of Russia as a major power was a matter of concern to other European nations. The country directly in Russia's path of expansion was Poland. At one point, Poland had been a major power in its own right that had picked on the emerging Russian state. Now the tables were turned. Russia was a growing giant, and Poland was crumbling to pieces, largely because of a powerful nobility and weak elective monarchy. Frederick also had his eyes on Poland, in particular the lands cutting Prussia off from the rest of his lands in Germany. Since Russia, Prussia, and Austria were still exhausted from the Seven Years War, they agreed to divide part of Poland peacefully among themselves in 1771. However, their greed was not satisfied, and there were two more such partitions in 1793 and 1795, which eliminated Poland from the map. Since that time until the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in 1989), Poland has mostly lived under the yoke of foreign (mainly Russian) domination.

The American Revolution

In the West, the last major event before the French Revolution was the American War for Independence (1775-83). For once, Britain, the big colonial power, found itself ganged up on by France, Spain, and Holland. This war had two important results in Europe. First, it left France bankrupt, which helped spark the French Revolution. Second, it established a democratic republic that many Frenchmen saw as an inspiration for their own revolution and the spread of democratic ideas across Europe and the globe.