The Age of RevolutionsUnit 16: The Age of Revolutions (1789-1848)

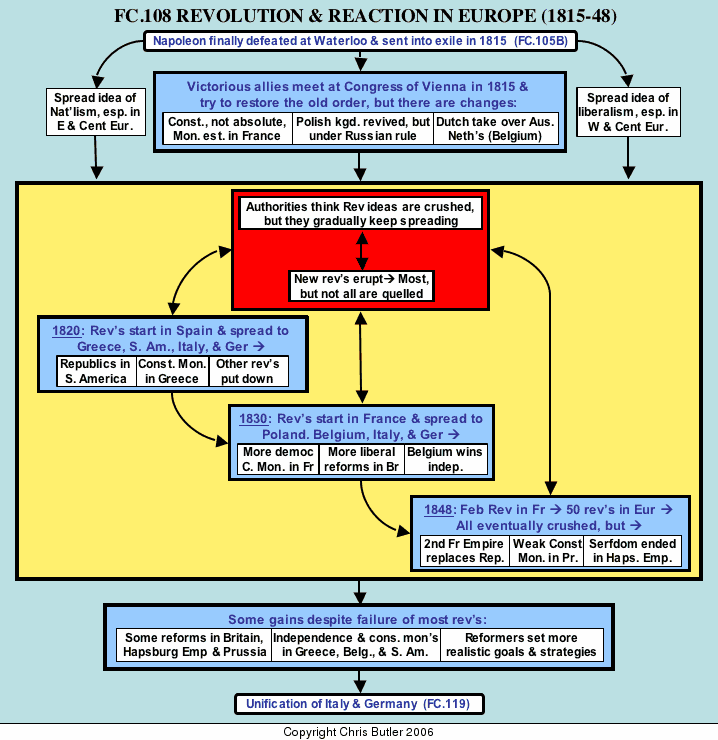

FC108Revolution and Reaction in Europe (1815-1848)

The Congress of Vienna

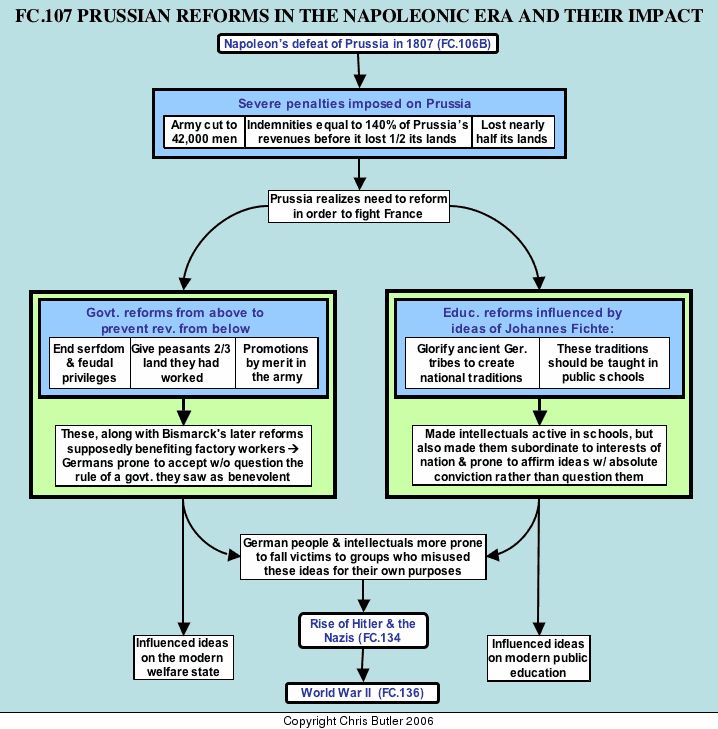

Despite his defeat, Napoleon had several important effects on Europe. For one thing, he had spread the idea of liberalism, especially in Western and Central Europe. By the same token, he had also spread the idea of nationalism in East and Central Europe. Finally, his defeat prompted the victors to meet at the Congress of Vienna with the goal of turning back the clock to restore the Europe that had existed before the French Revolution. This was especially the goal of the brilliant Austrian minister, Metternich who led much of the deliberations at Vienna.

The most pressing issue was what to do about France: punish it for causing all this trouble, or restore it to its former position as one of the great powers. Realizing that breaking up France would upset the balance of power, destabilize Europe, and lead to more revolutions, the allies restored it to its old position, punishing it with only a mild indemnity and short military occupation. However, the new king, Louis XVIII, was a constitutional, not an absolute monarch. Even in defeat, the French Revolution had made progress.

There were other changes in the political map of Europe and the world. Britain took South Africa from the Dutch to secure its sea route to India. In compensation, the Dutch got the Austrian Netherlands from Austria, which in turn received control of Northern Italy. The Grand Duchy of Warsaw formed by Napoleon, continued to exist as the Kingdom of Poland, although its king also happened to be the Czar of Russia. And Germany, thanks largely to Napoleon's administrative work, was consolidated into 38 states. These last three changes would all contribute to nationalist revolts in succeeding years.

For the time being, the Congress of Vienna did restore the old order and a period of relative international peace known as the Concert of Europe, since it saw the major powers working largely together for several years to guard the common peace and old order. However, the ideas born in the French Revolution and spread by Napoleon had not been eliminated. The seeds of revolution had taken root and were spreading rapidly across the face of Europe. Like it or not, the age of kings was in its twilight and a new age of democratic and nationalistic reforms and upheavals was dawning.

The pattern of revolts

The period 1815-48 saw periods of apparent tranquility broken by recurring waves of revolution. In two of three cases (1830 and 1848), these revolutionary movements started in France and inspired similar outbreaks all over Europe. Generally, revolutions in Western Europe focused on liberal reforms, since, with the exception of Belgium, nation states with a strong middle class were already established there. Eastern Europe, with its multi-national empires, saw more nationalist uprisings as various ethnic groups wanted independence from the Hapsburg, Ottoman, and Russian empires. Germany and Italy, in the middle of Europe, were especially turbulent since they were striving for both national unification and liberal civil rights.

A basic pattern of events emerged during this period. Authorities would think they had crushed the ideas of liberalism and nationalism. However, they had merely driven these ideas underground where they would continue to spread and revolutions would flare up again. While most of them would be suppressed, one or two would succeed and might prompt more liberal reforms in countries where the uprisings had been put down. Rulers would again think they had suppressed the revolutionary ideas, and the cycle would repeat. There were three major waves of revolutions: in the 1820's, 1830's, and 1848.

In 1820 the revolutions started in Spain and spread to Greece, South America, and Germany. Most of these were put down, but Greece and the South American colonies did win their independence, with a constitutional monarchy established in Greece and republics in South America. The next wave of revolutions would start in France in 1830 and spread to Poland, Belgium, Italy, and Germany. While the uprisings in Germany, Italy, and Poland were crushed, France won a slightly more liberal constitutional monarchy, Belgium won its freedom, and more liberal reforms were peacefully passed in Britain.

The final, and biggest, wave of revolutions occurred in 1848, with some fifty uprisings taking place across Europe. The French this time established a republic, only to have it taken over by a dictator, Napoleon III, and turned into the Second Empire. Elsewhere, other revolutions collapsed, but they did lead to some reforms. Serfdom was abolished in the Hapsburg Empire while a weak constitutional monarchy was established in Prussia. Despite apparent failure, nationalist reformers would learn from their mistakes and set more realistic goals and strategies toward attaining national unity in Germany and Italy by 1871.

Revolutions in the 1820's

It took only five years before a new wave of revolutions threatened the old order recently reestablished by Metternich and the Congress of Vienna. Ironically, it was one of the more backward countries of Western Europe, Spain, that led the way. A number of liberal army officers, apparently influenced by the ideas of the French Revolution, rebelled against the corrupt and repressive rule of the Bourbon king, Ferdinand VII. As if on cue, riots and revolts broke out all over: in Italy, Germany, Russia (1825), the Spanish American colonies, and Romania and Greece in the Ottoman Empire. In most cases these revolts were put down. Austria suppressed the revolts in Italy and unrest in Germany. France, despite some protests from Britain, put down the revolution in Spain. The new czar, Nicholas I, had no trouble crushing the Decembrist Revolution led by liberal army officers (many of whom thought that their battle cry, "Constantine and Constitution", referred to their liberal candidate for the throne, Constantine, and his wife. Likewise, the Ottoman Turks put down the Romanian uprising.

However, in two cases on the fringes of European power, Greece and the Spanish American colonies, revolutions succeeded for reasons peculiar to each situation. In the case of the Greek revolt, it was largely a romantic sentiment for ancient Greece, home of democracy and Western Civilization that sparked popular support for the Greeks. The fact that the Greek rebels were descendants of Slavic invaders of the early middle ages, not the Greeks from the time of Pericles and Socrates, made little impact on the European public. In fact, many of them, including the Romantic poet, Byron, went there as freedom fighters. In the end, the European powers, having little regard for the non-Christian Turks and fearing Russian aggression that might threaten the balance of power in southeastern Europe, pressured the Ottomans to grant Greece its freedom. In the style of the day, the Greeks established a constitutional, not absolute, monarchy in 1832. It was the first major break in the old order since the Congress of Vienna.

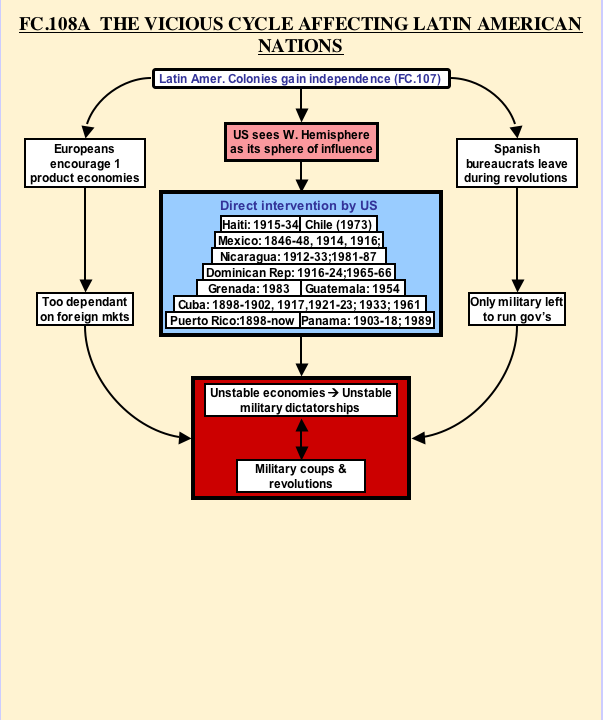

Latin America

The Spanish American colonies had taken advantage of the revolution in Spain to throw off the yoke of Spanish rule. Much of their inspiration came from the newly formed republic to the north, the United States. It was the United States that also stood up to protect the Americas from foreign intervention in the famous Monroe Doctrine in 1823. More important than the fledgling American republic's stand was Britain, which supported the revolutions so it could break Spain's mercantilist monopoly on trade and open new markets for British merchants to exploit. Spain could ignore the Monroe Doctrine, but it could not ignore the power of the British navy, so its American colonies went free.

However, independence brought two sources of instability to Latin America (covered in FC.108A). For one thing, most Spanish bureaucrats fled back to Spain, leaving few trained bureaucrats to handle government business. As a result, the armies that won the revolutions were often the only means of keeping matters under control. Second, with Latin American markets now open for free trade, Britain and other European countries encouraged the production of one type of commodity in each nation, such as beef in Argentina or copper in Chile. This made each new nation too dependent on international markets for its one product. Therefore, if the market for their product fell, their economy would have nothing else to fall back upon. This happened to El Salvador in the late 1800's when cheaper industrially produced dyes destroyed the need for its indigo dye, thus wrecking its economy. Together, these factors led to unstable economic and political structures in Latin America encouraging rule by military dictatorships. Misrule and poor economic conditions would lead to more military coups and revolutions, that would further destabilize the economy and the new government, leading to more revolutions and so on.

Revolutionary fever spreads: the 1830's

By the mid 1820's, most of Europe was pacified once again. However, the ideas of nationalism and liberalism, still simmering under the surface, broke loose again in 1830. Once again, the trouble started in France. The government of the restored king, Louis XVIII (1815-24), was a conservative constitutional monarchy with a legislature elected by a narrow electorate of 100,000 property owners. Louis realized that, after a quarter century of revolution, he had to treat the French people with care. His brother and successor, Charles X (1824-30) was not so wise. He censored the press, restored the clergy's position in the schools and politics, tried to bring back feudalism, gave pensions to nobles who had lost lands and rights from the Revolution, and dissolved the legislature.

In 1830, the Parisians revolted and barricaded Paris' narrow streets. The army refused to fire on the crowd, and Charles fled to England (a common habit for deposed kings back then). Now the question was: what type of government to set up. Students, intellectuals, and the Parisians wanted a republic. However, the middle class, probably with the backing of the more conservative peasantry, prevailed in its desire for a constitutional monarchy. The new king, Louis Philippe, known as the "Citizen King", was a man with little to commend him except that he was both a Bourbon and a former revolutionary, thus a compromise candidtate who satisfied no one. Admittedly, his constitution was a bit more liberal than the previous one, with 200,000 property owners given the right to elect the legislature. Things did settle down in France for a few years, but not before revolutionary turmoil flared up all over Europe.

Word of events in France triggered revolts in Belgium, Italy, Germany, and Poland, plus giving further impetus to a reform movement in Britain. Austria put down the uprisings in Germany and Italy, while Czar Nicholas I easily crushed the Polish rebellion against Russia. The one successful revolution was in Belgium where religious and linguistic differences with the ruling Dutch caused deep resentment that erupted into open rebellion in 1830. Austria and Prussia wanted to put this revolt down, but France and Britain supported the Belgian cause, largely to keep the other two powers from meddling so close to their shores. Since Austria and Prussia were also preoccupied with the Polish revolt, France and Britain could pressure Holland to recognize Belgian freedom in 1831. As was becoming the norm, a constitutional monarchy was established.

Although Britain did not experience revolution, it did see a strong reform movement that liberalized the criminal code and culminated in the Reform Bill of 1832. Electoral representation was redistributed to reflect the shift in population to the rapidly industrializing northern counties. The vote was extended to about 20% of British men (twice of what it was before). The Reform Bill of 1832 also opened the door for more liberal reforms as the century progressed: extending the vote to urban workers (1867) and miners (1884) and also instituting the secret ballot. Finally, after a long struggle, even women would get the vote in 1917. Although Britain remained technically a constitutional monarchy, by the early part of this century it was essentially a modern democracy.

The Revolutions of 1848

The success of revolutionary and reform movements in Western, Europe and frustration at the failure of other similar movements in Central and Eastern Europe led to the spread of liberal and nationalist ideas in the 1830's and 1840's. Economic forces also played a role in spreading discontent. A series of bad harvests in the 1840's caused starvation (with one million people dying in Ireland from a severe potato famine), which led in turn to higher food prices, bankruptcies, unemployment and urban unrest. Once again, events in France sparked a new wave of revolutions.

The government of the "Citizen King", Louis Philippe, had proven to be conservative, corrupt and unpopular, and in 1848 revolution broke out in Paris. Just like in 1830, the barricades went up in Paris' narrow streets, many soldiers refused to fire on the crowd, and the king fled to Britain. And just like before, revolutionary fever spread all over Europe, with close to 50 revolutions erupting in the German states, Italian states, and Hapsburg Empire.

The suddenness and scale of the uprisings caught rulers completely by surprise. In Germany, they agreed to more liberal constitutions, while a convention was held at Frankfurt to establish a national parliament for all of Germany. In Italy, the Austrians were driven out of Milan and Venice, while rulers in Naples, Tuscany, and Piedmont agreed to liberal reforms. In the Hapsburg Empire, a Hungarian revolt triggered similar revolts by Czechs, Croats, Galicians, and Transylvanians living under Hapsburg rule. Metternich, the conservative prime minister and architect of the Congress of Vienna, was forced to resign, and the emperor fled to Innsbruck. It seemed like the old regime was about to collapse all over Europe. But just as events in France had set off these revolutions, events there led the way in suppressing them.

This time, the French established a republic where all Frenchmen could vote for delegates to a convention to draw up a new constitution. However, it reflected the more conservative views of French peasants and middle class, which touched off riots by the urban masses suffering from lack of food and shelter in the recent economic troubles. The army met the crowd's cry of "Bread or Lead" with a hail of lead from artillery fire, killing 10,000 demonstrators. This was a turning point in suppressing radicals both in France and across Europe.

In France, the establishment of the Second Republic led to the election of Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew, Napoleon III, who, like his uncle, used a military coup to extend his presidency and then make himself emperor of the Second Empire (1852-70). Victor Hugo, in his The History of a Crime, described this coup in grim terms that probably would apply to such events at any time:

"Suddenly, at a given signal, a...shower of bullets poured upon the crowd....Eleven pieces of cannon wrecked the Sallandrouze carpet warehouse. The shot tore completely through twenty-eight houses. The baths of Jouvence were riddled. There was a massacre at Tortoni's [cafe]. A whole quarter of Paris was filled with an immense flying mass, and with a terrible cry....

"Adde, a bookseller of 17, Boulevard Possonniere, is standing before his door; they kill him. At the same moment, for the field of murder is vast, at a considerable distance from there, at 5, Rue de Lancry, M. Thirion de Montauban, owner of the house, is at his door; they kill him. In the Rue Tiquetonne, a child of seven years, named Boursier, is passing by; they kill him. Mlle. Soulac, 196, Rue du Temple, opens her window; they kill her...

"New Year's Day was not far off, some shops were full of New Years' gifts. In the Passage du Saumon, a child of thirteen, flying before the platoon firing, hid himself in one of these shops, beneath a heap of toys. He was captured and killed. Those who killed him laughingly widened his wounds with their swords. A woman told me, 'The cries of the poor little fellow could be heard all through the passage.' Four men were shot before the same shop....

"At the corner of the Rue du Sentier an officer of Spahis, with his sword raised, cried out, '...Fire on the women.' A woman was fleeing, she was with child, she falls, they deliver her by the means of the butt-ends of their muskets. Another, perfectly distracted, was turning the corner of a street. She was carrying a child. Two soldiers aimed at her. One said, 'At the woman!' And he brought down the woman. The child rolled on the pavement. The other soldier said, 'At the child!' And he killed the child....

"In the Rue Mandar, there was, stated an eyewitness, 'a rosary of corpses,' reaching as far as the Rue Neuve Sainte-Eustache. Before the house of Odier twenty-six corpses, thirty before the Hotel Montmorency. Fifty-two before the Varietes, of whom eleven were women. In the Rue Grange-Bateliere there were three naked corpses. No. 19, Fauborg Montmartre, was full of dead and wounded. A woman, flying and maddened with dishevelled hair and her arms raised aloft, ran along the Rue Poissoniere, crying, 'They kill! they kill! they kill! they kill! they kill!'"

Despite its violent beginning, Napoleon III's rule was much more peaceful than that of his uncle. France's prosperity rapidly grew as he promoted the building of industries and a centralized railroad network. He also put Paris through an extensive urban renewal project, providing the city with wide boulevards that critics were quick to point out could not be barricaded so easily in the event of revolution. Napoleon's reign would come to an end in 1870 after a disastrous war against Prussia in its final stage of unifying Germany. In his wake came the Third Republic of France. With the exception of Nazi rule in the 1940's, democracy has prevailed in France ever since.

Meanwhile, in the rest of Europe, the defeat of the more radical elements in France gave heart to other kings and princes reeling from the current wave of revolutions. Uprisings in Italy, Germany, and the Hapsburg Empire, were crushed as quickly as they had erupted and nearly overthrown established governments. By the end of 1848, the old regimes were back on top, and nothing seemed to have been gained.

Even in failure, the revolutions of 1848 did have positive results. For one thing, several reforms, such as the abolition of serfdom in the Hapsburg Empire and the granting of at least nominal constitutions in the German states signaled some progress. The spirit of reform extended even further east to Russia where serfdom was abolished in 1861. Second, despite their failure, the revolutions spread the popularity of liberal and nationalist causes. Failure also taught reformers to be more realistic in trying to attain more liberal reforms or national unification. Two such men in particular, Camillo Cavour in Italy and Otto von Bismarck in Germany, clearly recognized these lessons and skillfully put them to work in building nations forged, as Bismarck would put it, from "blood and iron".

FC108AThe Vicious Cycle Affecting Latin American History

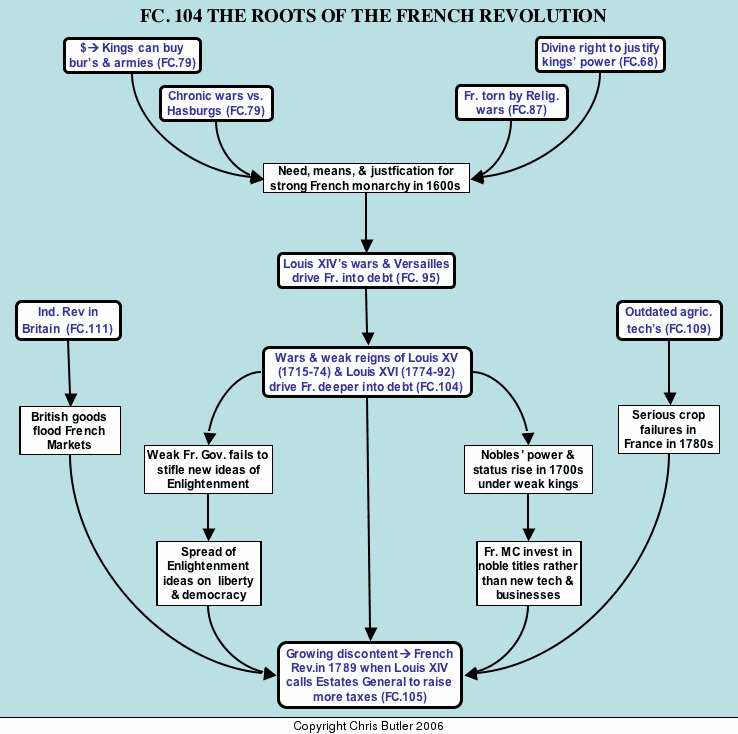

FC104The Roots of the French Revolution

“Walking up a long hill to ease my mare, I was joined by a poor woman, who complained of the times, and that it was a sad country. Demanding her reasons, she said her husband had but a morsel of land, one cow, and a poor little horse, yet they had a franchar (42 pounds) of wheat and three chickens to pay as a quitrent to one seigneur; and four franchar of oats, one chicken, and one franc to pay to another, besides very heavy tailles (income tax) and other taxes. She had seven children and the cow's milk helped to make the soup. 'But why, instead of a horse, do not you keep another cow?' Oh, her husband could not carry his produce so well without a horse; and donkeys are little use in the country. It was said, at present, that something was to be done by some great folks for such poor ones, but she did not know who nor how, but God send us better, 'car les tailles et les droits nous ecrasent' (for the taxes are crushing us).

“This woman, at no great distance, might have been taken for sixty or seventy, her figure was so bent and her face so furrowed and hardened by labor, but she said she was only twenty-eight. An Englishman who has not traveled cannot imagine the figure made by infinitely the greater part of the countrywomen in France; it speaks, at the first sight, hard and severe labor. I am inclined to think that they work harder than the men, and this, united with the more miserable labor of bringing a new race of slaves into the world, destroys absolutely all symmetry of person and every feminine appearance.”— Arthur Young, Travels in France during the Years 1787, 1788, and 1789

The French Revolution, along with the Industrial Revolution, has probably done more than any other revolution to shape the modern world. Not only did it transform Europe politically, but also, thanks to Europe's industries and overseas empires, the French Revolution's ideas of liberalism and nationalism have permeated nearly every revolution across the globe since 1945. In addition to the intense human suffering as described above, its origins have deep historic and geographic roots, providing the need, means, and justification for building the absolute monarchy of the Bourbon Dynasty which eventually helped trigger the revolution.

The need for absolute monarchy came partly from France's continental position in the midst of hostile powers. The Hundred Years War (1337-1453) and then the series of wars with the Hapsburg powers to the south, east, and north (c.1500-1659) provided a powerful impetus to build a strong centralized state. Likewise, the French wars of Religion (1562-98) underscored the need for a strong monarchy to safeguard the public peace. The means for building a monarchy largely came from the rise of towns and a rich middle class. They provided French kings with the funds to maintain professional armies and bureaucracies that could establish tighter control over France. Justification for absolute monarchy was based on the medieval custom of anointing new kings with oil to signify God's favor. This was the basis for the doctrine of Divine Right of Kings. In the late 1600's, all these factors contributed to the rise of absolutism in France.

Louis XIV (1643-1715) is especially associated with the absolute monarchy, and he did make France the most emulated and feared state in Europe, but at a price. Louis' wars and extravagant court at Versailles bled France white and left it heavily in debt. Louis' successors, Louis XV (1715-74) and Louis XVI (1774-89), were weak disinterested rulers who merely added to France's problems through their neglect. Their reigns saw rising corruption and three ruinously expensive wars that plunged France further into debt and ruined its reputation. Along with debt, the monarchy's weakened condition led to two other problems: the spread of revolutionary ideas and the resurgence of the power of the nobles.

Although the French kings were supposedly absolute rulers, they rarely had the will to censor the philosophes' new ideas on liberty and democracy. Besides, in the spirit of the Enlightenment, they were supposedly "enlightened despots" who should tolerate, if not actually believe, the philosophes' ideas. As a result, the ideas of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu on liberty and democracy spread through educated society.

Second, France saw a resurgence of the power of the nobles who still held the top offices and were trying to revive and expand old feudal privileges. By this time most French peasants were free and as many as 30% owned their own land, but they still owed such feudal dues and services as the corvee (forced labor on local roads and bridges) and captaineries (the right of nobles to hunt in the peasants' fields, regardless of the damage they did to the crops). Naturally, these infuriated the peasants. The middle class likewise resented their inferior social position, but were also jealous of the nobles and eagerly bought noble titles from the king who was always in need of quick cash. This diverted money from the business sector to much less productive pursuits and contributed to economic stagnation.

Besides the Royal debt, France also had economic problems emanating from two main sources. First of all, while the French middle class was sinking its money into empty noble titles, the English middle class was investing in new business and technology. For example, by the French Revolution, England had 200 waterframes, an advanced kind of waterwheel. France, with three times the population of England, had only eight. The result was the Industrial Revolution in England, which flooded French markets with cheap British goods, causing business failures and unemployment in France. Second, a combination of the unfair tax load on the peasants (which stifled initiative to produce more), outdated agricultural techniques, and bad weather led to a series of famines and food shortages in the 1780's.

All these factors (intellectual dissent, an outdated and unjust feudal social order, and a stagnant economy) created growing dissent and reached a breaking point in 1789. It was then that Louis XVI called the Estates General for the first time since 1614. What he wanted was more taxes. What he got was revolution.

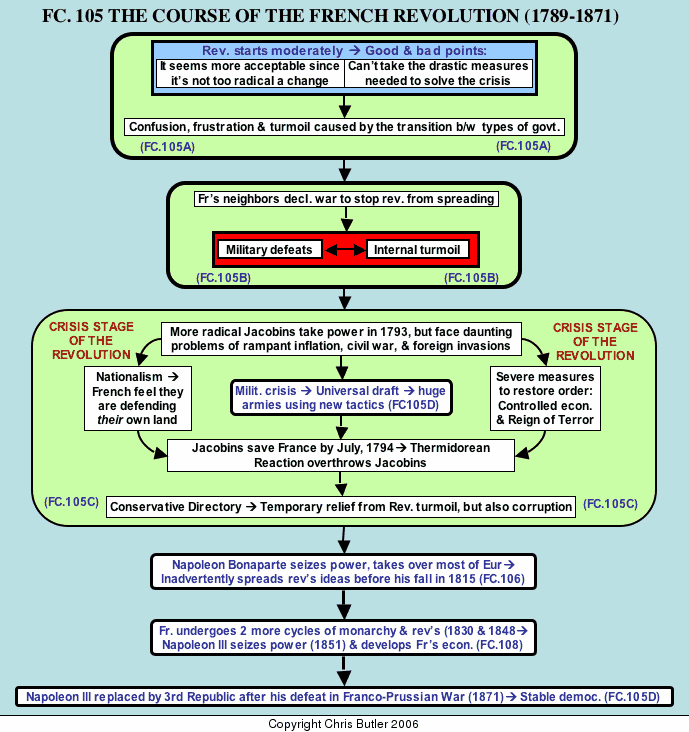

FC105Analyzing the French Revolution and Revolutions in General

Introduction

When analyzing the French revolution and revolutions in general, there are several recurring aspects we should keep in mind. For one thing, revolutions tend to develop like a fever that starts mildly, but worsens progressively until it reaches "fever pitch" and then breaks. This cycle may recur several times before matters finally are resolved. A second theory is that revolutions start out rebelling against an absolutist or arbitrary power and end up setting up another arbitrary power in its place. The French Revolution certainly fits into both of these patterns. Finally, the revolutions that succeed do so because the ruling regimes are too weak willed to crush the opposition early before matters get out of hand. That was the case with England in the 1640's, Russia in 1917, and certainly with France in 1789. However, even a corrupt and decaying government, is if it acts decisively at the start, can usually crush a revolution before it can spread and grow.

The French Revolution

All this makes sense when one considers that a revolution is against an order that people have come to depend on over a long time. Most people, however dissatisfied, are still reluctant to get rid of that "security blanket" and take their chances with something new and untried. Therefore, successful revolutions, like fevers, start off small and moderate. This has its good and bad points. For one thing, their moderation makes them seem safer to more people and does not invite a severe crackdown by the authorities. In fact, at this early stage, a revolution may seem more like a reform movement than a revolution. That was largely the case with the very moderate National Assembly that took power in 1789.

However, the very moderation that makes a new regime such as the National Assembly so widely acceptable also creates problems in a couple ways. First of all, in order to seem legitimate, the government feels it must hang onto many of the very policies and symbols that had triggered the revolution in the first place. In the National Assembly's case, it was keeping the king as a figurehead and honoring his debt. In the Russian Revolution it was keeping Russia in the First World War. In both cases, these policies, while making the new governments look more legitimate, also severely undercut their power. Second, the new regime's moderate policies keep it from taking the drastic measures necessary to solve the problems that led to revolution in the first place, since that would seem to betray the principles of the revolution. Despite these shortcomings, the new regime leads to high expectations that it will solve the nation's problems.

However, a major problem the new regime faces is that the transition to a new government will cause a good deal more confusion and turmoil before it starts turning things around. The new regime's failure to solve the nation's problems quickly just adds to the frustration of people who expect a quick fix to the country's problems and do not understand that solutions to such deeply rooted problems take time. This leads to a vicious cycle that will drive the revolution to a crisis stage.

First of all, more radical elements will exploit the government's problems and weaknesses in order to seize power. In France those "radicals" were the Girondins, who were still relatively moderate. They in turn found themselves faced with many of the same problems the original National Assembly had as well as high expectations that they would solve them. Unfortunately, the more radical the revolution gets, the more alarmed neighboring countries become about the prospects of the revolution spreading. Also the more turbulent the revolution, the more tempting it might be for outside powers to intervene for their own greedy purposes. This results in the other countries ganging up against the revolutionary country, as happened to France in 1792. Naturally, internal anarchy makes the revolutionary regime ill prepared for war and it starts losing. This creates more internal turmoil, giving a new group of radicals the opportunity to gain support and seize control, which is what the Jacobins did in France. This feeds back into alarming foreign powers who increase outside pressure on the revolution, thus triggering more confusion and turmoil, and so on.

At some point, this mounting feedback between internal anarchy and military defeat leads to three things. First of all, the revolution reaches a crisis stage where someone has to take firm control of affairs if the nation and revolution are going to survive. In the French Revolution, the Jacobins organized France into what was in essence a police state under the "reign of terror". However these measures, including a universal draft that led to huge armies by the standards of the day, did provide the internal order and productivity necessary to support France's armies.

However, the revolution has also unleashed two other factors that will help save it. One of these consists of new ideas and symbols, in particular nationalism, which inspired the French people to fight, sometimes with inspired fury, for a nation they now saw as their own, not the king's. Finally, the revolution freed the French to think in innovative ways, especially in the form of new military tactics introduced by a new generation of officers who had taken the place of the departed nobles. This combination of nationalism, new military tactics, and police state measures saved France in the crisis of 1793-94. But the revolution was not finished yet.

As stated above revolutions tend to go from arbitrary power to arbitrary power. This happened with Cromwell's military dictatorship in the English Revolution and with Lenin's dictatorship in Russia. It also happened in France.With the passing of the crisis of 1793-94 there was a backlash against the radical Jacobins and their reign of terror. A more moderate government, the Directory, took over and found many of the old problems (e.g., food shortages and inflation) re-emerging. It also found a new coalition of foreign enemies ranged against it, even more scared of the revolution after its recent, nearly miraculous comeback. In such a situation, the solution lay with the army, much as it did with Cromwell's New Model Army in England and Lenin's Red Army in Russia. Likewise, in France, it was an ambitious young artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte, who seized power and established a military dictatorship.

On the surface, it may seem that Napoleon killed the French Revolution and that nothing had been gained. However, one should keep in mind it was powerful revolutionary forces that brought him to the top and gave his army the power to march across and dominate Europe. Napoleon may have tamed the revolution's more chaotic aspects and stifled its more radical innovations (especially in the way of democracy), but he also consolidated it. He kept and expanded its administrative and economic reforms. He codified into law its principles of social and legal equality for all men. And he shamelessly used the concept of nationalism to inspire his armies in battle. He also provided the stability necessary for economic growth and the further rise of the middle class. And it was the combination of repressing parts of the revolution and fostering others that gave Napoleon and France the power to conquer or dominate nearly all Europe by 1807.

Whether or not he meant to, Napoleon also spread the revolutionary ideals of liberalism and nationalism across Europe where they took root and grew into a force largely responsible for his eventual defeat. Foreign powers armed the masses and invoked the power of their own nationalism to defeat Napoleon by 1815. Long after Napoleon the ideas of the revolution imbedded in the law codes he had imposed upon Europe continued to take root and grow, first in Europe, and then by way of Europe's colonial empires, across the globe. Then it was the turn of non-Europeans to use the powerful ideas of the French Revolution to overthrow European rule in much the same way that Europeans had used those same ideas to overthrow Napoleon. When put into that kind of perspective, one can see what a powerful force the French Revolution has been in modern history.

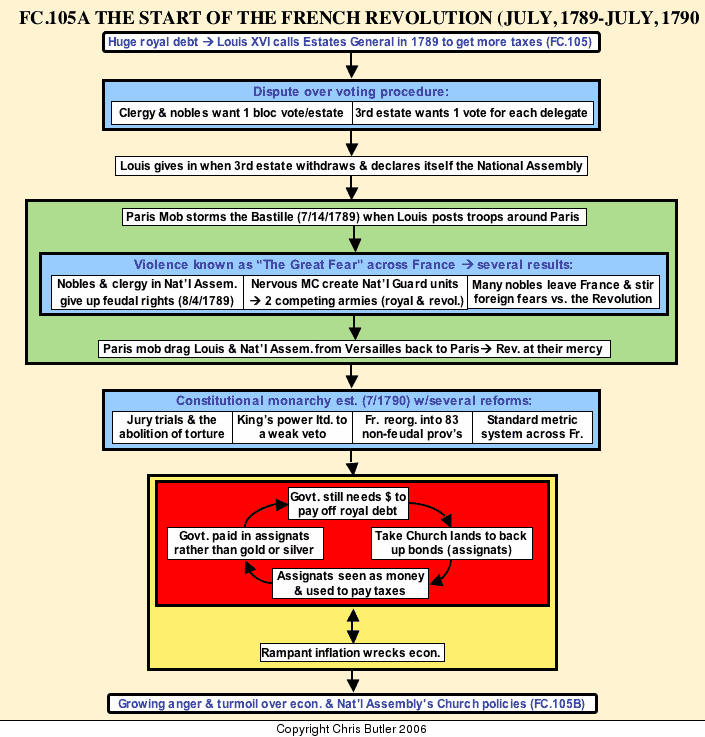

FC105AThe Start of the French Revolution (July, 1789- July, 1790)

Hopes ran high for widespread reforms when Louis XVI called the Estates General to Versailles in the spring of 1789. While Louis' main concern was to get more taxes to cover France's mounting debts, the delegates from the Third Estate (mostly middle class lawyers and businessmen) came with notes ( cahiers) from their constituents urging such reforms as taxing the clergy and nobles to even the tax burden. However, before these issues could be addressed, a more basic problem arose: voting procedure.

The First and Second Estates (clergy and nobles respectively) wanted bloc voting where each estate's votes collectively counted as one vote. This would give the nobles and clergy two votes to one for the Third Estate (representing the middle and lower classes who comprised 98% of France's population). Therefore, the Third Estate, whose delegates equaled the combined number of noble and clergy delegates, wanted one vote per delegate. Since a number of liberal clergy and nobles would probably vote with the Third Estate, this would give the Third Estate an effective majority of votes.

The decision belonged to Louis, whose weak and indecisive nature let matters get out of control. On June 17, the Third Estate, seeing the king's indecision, put pressure on him by withdrawing along with many poor delegates from the clergy and declared themselves the National Assembly with the exclusive right to grant taxes. When Louis locked them out of the Assembly Chamber, they withdrew to an indoor tennis court and took what became known as the Tennis Court Oath, vowing never to separate until they had formed a constitution. Somehow, a meeting about taxes had turned into a movement to form a new government. On June 27, Louis gave in and ordered the First and Second Estates to merge with the National Assembly. The Revolution had begun.

Two weeks later, on July 10, Louis, under pressure this time from the nobles, ordered troops to surround Paris and Versailles. The next day he fired a popular finance minister, Neckar, who had advocated taxing the nobles. These acts, plus continued food shortages triggered demonstrations in Paris that culminated in the storming of the Bastille (7/14/1789), an old prison with so little value that Louis himself had plans for tearing it down. Despite this, the Bastille was a symbol of oppression and its storming has been celebrated ever since as France's Independence Day.

All across France the Bastille's fall touched off the Great Fear, waves of violence in which armed bands of peasants killed nobles and royal officials, burned chateaus, and destroyed records of feudal obligations. This created several effects. First, concerned property owners in cities throughout France took the lead from Paris and formed their own National Guard units to protect themselves and their property. As a result, France now had two armies: the king's royal army and the revolution's National Guard. Also, the mounting violence and chaos started a wave of nobles emigrating to other countries. Successive waves of emigration would bring stories of ever mounting turmoil in France that would stir up foreign fears, hostility, and eventually full scale military attempts to overthrow the revolution. The resulting wars would rage across Europe for a quarter century.

Finally, fear of violence also seems to have affected the National Assembly. On the night of August 4, 1789, nobles and clergy surrendered their feudal rights and privileges in a remarkable show of generosity (or fear). In one fell swoop, feudalism had been abolished in France, although the final draft of the document did give compensation to the nobles and clergy and delayed dismantling the feudal order.

In much the same spirit, the National Assembly issued the "Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen" (8/27/1789). This remarkable document declared for all men, not just Frenchmen, the basic ideals of the revolution: liberalism (the belief in civil and political rights and liberties for all men) and nationalism (the belief that a people united by a common language and culture should control its own destiny). These two principles have proven to be two of the most powerful ideas in modern history.

Center stage now moved back to the Paris mob of laborers and small shopkeepers, known popularly as the sans culottes from their wearing long pants rather than the more fashionable short breeches (culottes) of the upper class. Partly inspired by the Great Fear and the acts of the National Assembly, but even more by continued food shortages, they marched on Versailles and brought the king and National Assembly back to Paris to ensure they would relieve the suffering of the urban poor. From this point on, the sans culottes would exact an ever more powerful and radical influence on the French Revolution, a power and influence far out of proportion to their numbers.

However, the Revolution at this point was still a fairly mild and civilized affair controlled by moderate middle class delegates. It was the enlightened ideas of such philosophes as Rousseau and Voltaire plus the growing need for reforms, not pressure from the sans culottes, that mainly influenced the constitutional monarchy they established in July, 1790. Power mostly resided in the National Assembly, with the king having only a weak temporary veto on its actions. In order to weaken old feudal loyalties, France was broken up into 83 new provinces known as departements, the basis of France's administration to this day. Jury trials were established, torture was outlawed, and a more humane form of execution, the guillotine, was introduced. Internal tolls were abolished, and a standard system of weights and measures, the metric system, came into use. The new constitution definitely had a narrow middle class bias, as seen by its measures to improve trade plus its property qualifications for voting that shut out all but 4,000,000 Frenchmen from full citizenship. It was a combination of the new government's more progressive measures and shortcomings that would lead to more radical reforms.

One problem the National Assembly did not solve was the huge royal debt that had started the revolution in the first place. Since the king was kept as constitutional figurehead of the government in order to make it look legitimate, the National Assembly could not repudiate the royal debt and still seem credible. Therefore, it came up with one of the more innovative policies of the revolution: confiscation of Church lands, the value of which would back up government bonds called assignats. The National Assembly originally sold 400,000,000 francs worth of assignats to pay off its most urgent debts.

Unfortunately, many people saw the assignats as money and used them rather than hard cash to pay their taxes. As a result, the Government, finding itself still in need of cash, issued more assignats and the cycle started all over. There were two main results of the government's Church policies. First of all, the flood of assignats triggered an inflationary cycle that destabilized the French economy and political structure. By the end of the revolution, the assignats were only worth 1% of their face value. Second, many people were angry over the state's control of the Church that extended to electing priests and making them swear a loyalty oath to France. Both of these would combine to unleash forces making the revolution more radical and violent.

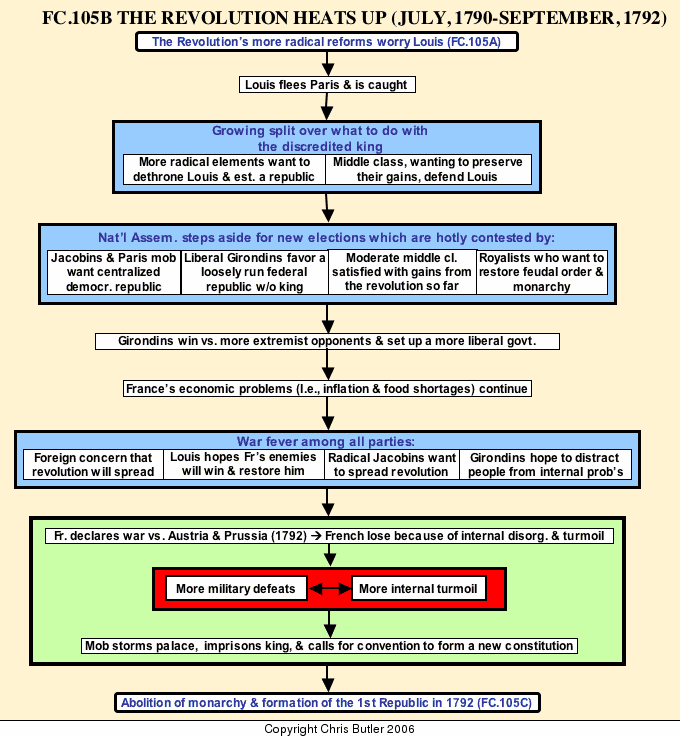

FC105BThe Revolution Heats Up (July, 1790-- Sept., 1792)

At the first annual celebration of the revolution 50,000 National Guardsmen from all over France and 300,000 Parisians witnessed the king taking an oath of loyalty to the new constitution. However, Louis was not loyal to the revolution since it severely restricted his power and even prevented him from leaving Paris to attend Mass in the country. On June 20, 1791, the king tried to escape to the Austrian Netherlands and seek refuge with the Hapsburgs. Unfortunately for Louis, everything went wrong. Detachments of royal troops failed to meet him in time. Then, despite Louis' disguise as a German servant, a postmaster at Varennes recognized him from his portrait on the assignats. The postmaster called out the National Guard who captured Louis and escorted him back to Paris. Whatever faith most people may have had in their king before was now shattered by his attempted betrayal of the revolution.

Louis' foiled flight was a turning point in the revolution. First, it further alarmed foreign royalty about the mounting revolutionary threat in France. Second, it widened the rift between the radicals who wanted a republic (democracy without a king) and the bourgeoisie (upper middle class) who wanted to keep the king as figurehead to maintain the moderate respectable image of the revolution. To protect Louis and their position, they claimed the king had not fled but had been kidnapped. At the same time they suspended Louis' powers. But the damage had been done. In July, a demonstration of 50,000 Parisians demanding Louis's abdication turned violent and the National Guard killed 50 demonstrators. The revolution was starting to fragment.

On September 30, 1791 the National Assembly dissolved itself after over two years of leading the revolution. One of its last acts was to exclude its members from re-election to the new National Assembly, thus bringing in new blood, but also eliminating many experienced leaders from participation as well.

The elections of 1791 showed how fragmented the revolution was becoming. On the left wing (sitting to the left of the speaker's platform in the assembly) were the radicals led by the Jacobins who wanted a more strongly centralized republic. Next to them and controlling the most votes were the Girondins who also favored a republic, but with more provincial freedom from central control in Paris. Just to the right of them were moderates who were happy with their gains from the revolution and resisted further change. To the far right were the monarchists who wanted to restore the feudal order and the king's power. These were not so much organized political parties as they were loosely organized networks of political clubs united by a common political philosophy.

While the Girondins had been able to exploit the moderates' problems in order to gain power, they soon found themselves faced with the old issues of food shortages, inflation, and debt. A new problem was also surfacing that would soon overshadow the rest: war. Ironically, this was the one issue most people agreed on, but for widely different reasons. Louis and the monarchists saw war as a chance for Austria and Prussia to crush the revolution and restore the king to power. The Girondins saw it as an opportunity to discredit Louis and spread the revolution across Europe. War could also divert attention from France's internal problems. Many Frenchmen saw war as a means of preventing nobles from returning to reclaim their lands and feudal rights. Austria and Prussia wanted war to prevent the revolution from spreading outside of France. With everyone in such agreement, France declared war on Austria and Prussia (4/20/1792). This triggered a series of wars between France and the rest of Europe that would last, with few breaks, for 23 years.

The government was optimistic about the war. It should have known better. The combination of old and new debts plus inflation triggered by the assignats had left the treasury in shambles. Likewise, the incomplete transition from the royalist army to a national one had left the army in disarray. Royalist and National Guard units operated separately from one another. Noble officers had either fled or were of suspect loyalty. And the troops, while enthusiastic, were poorly trained, supplied, and led.

The result was a total fiasco as French troops fled at the first sight of the enemy. Charges of treason flew everywhere, especially against Louis, who probably was plotting with the enemy. An ultimatum ordering the French not to harm the king seemed to confirm suspicions of his guilt. On August 10, 1792, 9000 Parisians and National Guard troops stormed Louis' palace of the Tuileries. Louis, hating the sight of his own people's blood being shed, ordered his Swiss Guards to cease-fire. The mob massacred the guard, looted the palace, and turned Louis over to the Paris Commune who threw him into jail. The National Assembly, under heavy pressure from the sans culottes, agreed to new elections for a convention to form a new constitution. The monarchy was abolished and replaced by The First Republic, which would see the revolution through its trial by fire.

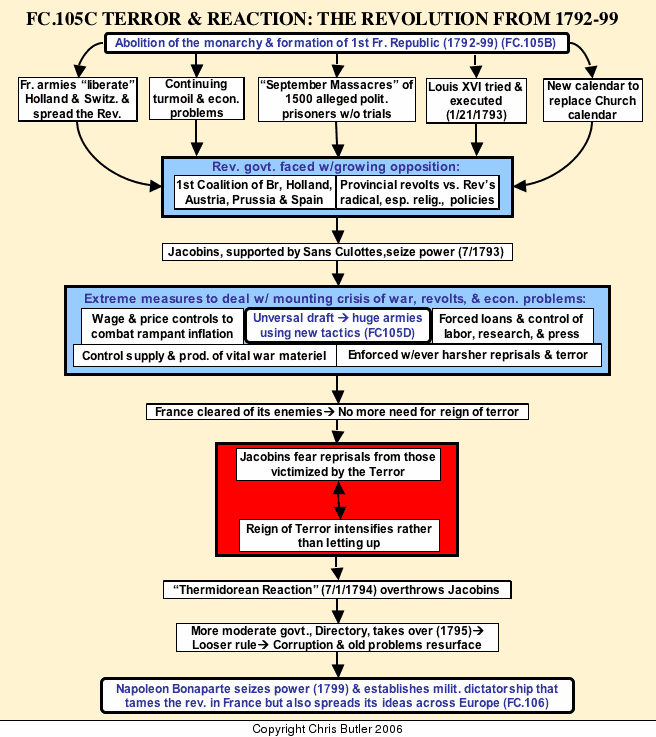

FC105CTerror and Reaction (Sept, 1792-Oct., 1795)

Growing chaos

Symbolic of the switch from monarchy to republic was a new calendar of twelve months with three 10-day weeks each. It started with Day I, Year I (9/22/1792) and stayed in effect for ten years. This new calendar was largely an attack on the Church and symbolized the revolution's complete break with the past. However, it was quite unpopular with the mass of French people who remained devout Catholics, showing how out of touch with the feelings of most French people the radicals in Paris were becoming.

Another break with the past came with the execution of Louis, whose fate hinged on the growing struggle between the Girondins, who wanted to limit Paris' influence on the revolution, and the radical Jacobins, who supported the sans culottes and used them in turn for support and intimidation. The Jacobins' call for putting Louis on trial forced the Girondins into the impossible choice of either giving in to radical pressure to try him or seeming like they were defending a very unpopular king. Louis' correspondence with the enemy sealed his fate as all the delegates voted him guilty of treason, and a narrow majority voted for execution. On January 21, 1793, Louis was executed and over 1200 years of French monarchy came to an end. In the process, the Girondins were quickly losing support to the Jacobins. Mounting problems of war, inflation, and food shortages would finish them off.

On September 20, 1792, the French Revolutionary armies won their first battle of the war at Valmy against a Prussian army largely preoccupied with the Second Partition of Poland and also ill from eating too many grapes. Inspired by this rather lackluster victory, French armies moved forward and overran Savoy, Nice, the Austrian Netherlands, and Holland. This prompted the National Convention to declare a revolutionary struggle to liberate all people from the tyranny of kings. Naturally, this alarmed kings across Europe and united them in The First Coalition to stop the French radicals. What had been a somewhat half-hearted fight of France against Austria and Prussia, now escalated into total war against practically all of Europe.

The tide of events once again quickly turned against France. Allied armies defeated the French, whose top general, Demouriez, and minister of war defected to the enemy. Meanwhile, western France was rocked by a major revolt of peasants protesting the revolution's church policies and military draft. As enemy armies closed in on France, the economy nearly collapsed. Inflation was rampant and the assignats fell to 50% of their face value. The resulting grain shortages triggered food riots in Paris by the sans culottes and the Jacobins, who called for strong price controls. Events were spinning out of control, and with each bit of bad news, the Girondins' position became more dangerous. Finally, on June 2, 1793, a crowd of 80,000 armed sans culottes and National Guardsmen overthrew the Girondins. The Jacobins took control and established a dictatorship under the Committee of Public Safety, a group of nine men whose most famous member, Robespierre, symbolized the reign of terror about to unfold.

Jacobin Rule

The government took control of vital resources and production of munitions to ensure adequate military supplies for its armies. Paris alone was producing 1000 muskets a day. Strict wage and price controls were imposed to stifle inflation. Massive forced loans helped finance the effort. Newspapers were strictly controlled to maintain morale. People wore wooden shoes to save leather for French soldiers' shoes. Even scientific research was directed toward the war effort as the famous chemist Lavoisier found a better formula for gunpowder.

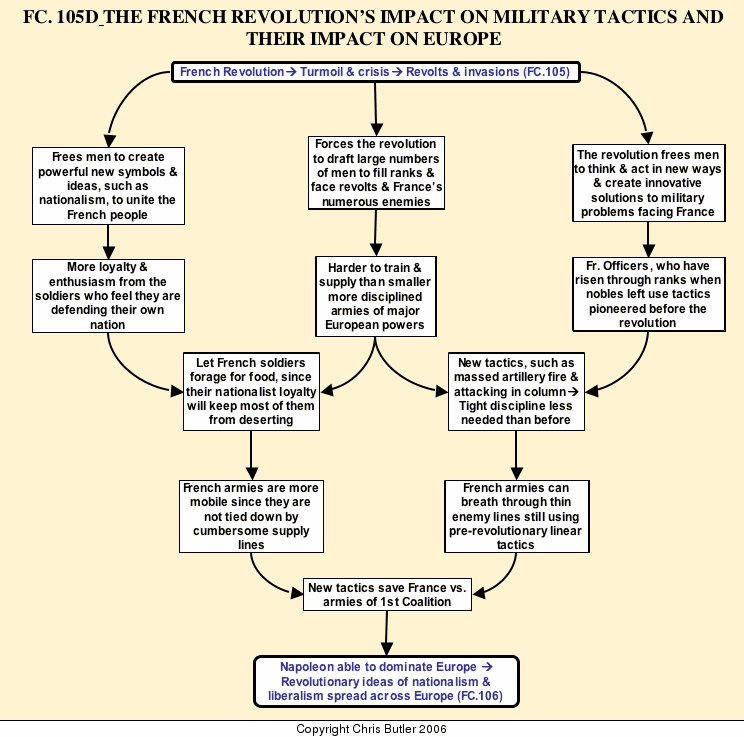

A military revolution

However, the Revolution also freed and inspired the French to create powerful new symbols and ideas, in particular nationalism. For the first time in history a people sharing the same language, culture, and government had found a unifying spirit to inspire them in the common defense of their homeland. For this was the France of the French people, not the French king, and that fact motivated the French soldiers to fight with a spirit totally lacking in mercenaries serving merely for money. Nationalism was what allowed these much larger French armies to forage, because desertion was less of a problem or threat to generals who knew their men had a cause to fight for. This, in turn, freed French armies from cumbersome supply lines, making them more mobile despite their numbers.

The Revolution also freed French generals from the traditional thinking of the old regime, allowing them to come up with innovative new tactics and formations. Many of these new generals had been junior officers who rose through the ranks to command positions left vacant when noble officers had fled France. In order to take advantage of the large numbers of recruits, they used massed firepower and charging in blocks or columns of men through strategic points of the enemy line. Together, the mobility, new tactics, and spirit of nationalism saved Fance from the armies of the First Coalition.

The Reign of Terror and Thermidorean Reaction

By the summer of 1794, the Committee of Public Safety's drastic measures had accomplished their purpose. They had suppressed the revolts, stabilized the economy, and secured France's borders. To many, the end of the crisis should have signaled the end of the government's repressive measures. But the Jacobins were caught up in their own cycle of repression and paranoia that merely intensified the Reign of Terror. Nearly 1400 people fell victim to the guillotine in Paris alone between June and July 1794. The Jacobins, increasingly out of touch with the feelings of most French people outside of Paris, shut down churches or turned them into "temples of reason" for their new Deistic style religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being. Growing fear and dissatisfaction with the Committee of Public Safety's Republic of Virtue finally led to a conspiracy known as the Thermidorean Reaction, which ousted Robespierre and his colleagues (7/28/1794).

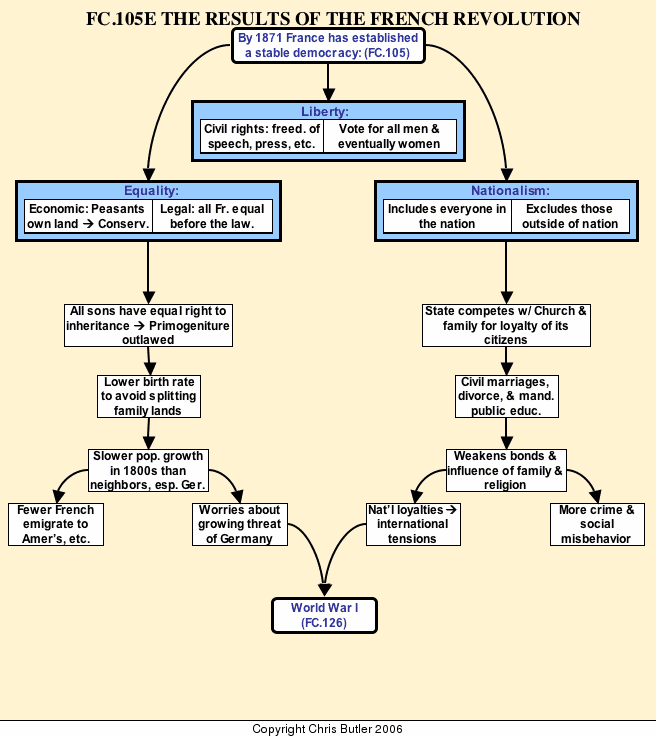

The revolution now started to wind down, but its effects did not. The results of the French Revolution can be summarized by the revolutionary motto: "liberty, equality, and brotherhood." Briefly put, liberty referred to the right of all men to live freely with certain guaranteed rights such as free speech and religion. Equality referred to the equality of all men before the law as opposed to the inequities of the old feudal system that the revolution had swept away. Brotherhood (nationalism) referred to the right of a people united by a common language and culture to be autonomous and live under its own laws and government.

In October 1795, a new constitution and government, the Directory, took over, but not without incident. An uprising against the new government threatened it before it even took over. A young artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte, was called in to save the day. With his famous "whiff of grapeshot," he saved the new government and launched his own career, which would spread French power across the continent. French power would not last, but the seeds of the revolution's liberal and nationalist ideals that were planted in the process would take root and transform the face of Europe and eventually the world.

FC105DThe French Revolution's Impact on Military Tactics

FC105EThe Results of the French Revolution

Although it would take until 1871 for the French Revolution to play out, it was triggering profound effects in France and the rest of Europe as early as 1789. One touchstone by which to analyze the Revolution’s results is its motto: “Liberty, Equality, and Brotherhood. The power of these three ideas would quickly spread to the rest of Europe, especially after Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815, and eventually across the globe.Liberty refers to the basic civil rights we often take for granted as being the natural rights of people everywhere, such as speech, press, assembly, religion, and voting for officials and laws, etc. The last of these, voting, was typically among the last to be extended to all members of society, in particular women.

Equality meant that everyone should be equal before the law, rather than face unjust double standards. At times, some of the more subtle effects of such an idea can magnify across history. This was especially the case with inheritance law in France. Since all men were seen as equal before the law, primogeniture was outlawed, giving all sons equal shares of an inheritance, and even daughters a portion, although less than the sons got. The problem with splitting up family lands into several smaller plots was that repeatedly dividing it into ever-smaller plots would make it impossible for all the heirs to support their families. Therefore, French peasants in the 1800s had a lower birthrate to avoid splitting family lands. This, however, reverberated over the following century in several ways. For one thing, few French people emigrated to places like the Americas compared to other European peoples. Likewise, there were fewer people available for factory work, which slowed France’s rate of industrialization. Also, the unification of Germany in 1870 prompted rapid industrialization and population growth that rapidly passed up France in both categories. By 1900 this would generate mounting worries in France about the growing threat of Germany that would help lead to World War I.

Brotherhood (AKA nationalism) was the idea that a people united by a common language; history, culture and geography should have the sovereign right to choose their own destiny. This would also prove a mixed blessing. On the plus side, nationalism included everyone sharing the traits just mentioned, bringing them into both a larger and more cohesive group. However, it also tended to exclude people not sharing the same nationalistic traits.

Another good news/bad news aspect of nationalism was the competition of the nation state with older institutions, in particular the family and religion, for the loyalty of its citizens. While some argued legalizing divorce and implementing civil marriages and mandatory public education helped nations get past some of the more regressive attitudes and narrow loyalties of the family and religion, the state has had difficulty adequately replacing those institutions in terms of moral and ethical education, social stability, and providing social services that used to be the task of church and family.

Nationalism, by weakening the bonds and influence of family religion, has often been blamed for both domestic and foreign problems. Domestically, many would say the nation state has contributed to rising crime rates and social misbehavior. In foreign affairs, nationalism’s exclusive nature has helped create, especially through public education, a sense of superiority over other nations, who reciprocate with their own feelings of superiority. By 1914 such attitudes would raise international tensions in Europe to levels that would trigger two disastrous world wars in the twentieth century.

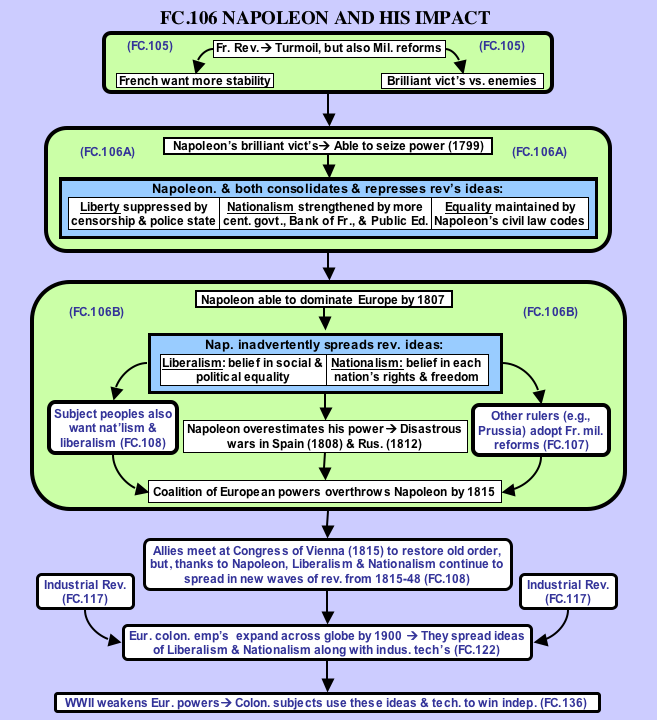

FC106Napoleon and his Impact (1799-1815)

Few men have dominated an age so thoroughly as Napoleon Bonaparte dominated his. In many ways he was like Adolph Hitler: charismatic, a master psychologist and politician, and ambitious to the point of self-destruction. Both started wars that led to vast destruction and a new political order. Both men shaped their times, but both were also products of their times who went with the currents of their respective histories and adeptly diverted those currents to suit their own needs. And ultimately, both were dismal failures.

To a large extent, Napoleon's career resulted from the military and political forces he inherited from the Revolution and exploited for his own purposes. In military affairs, he was lucky to inherit the military innovations of the French Revolution, such as mass conscription which made possible the use of block tactics in order to attack in column and eliminated the need for supply lines, thus making French armies much more mobile. Therefore, the two characteristics of Napoleonic warfare, massed firepower and mobility were already present when he started his career. However, it was Napoleon's genius that knew how to use them effectively in his first Italian campaign against the Austrians.

Politically, France had suffered a full decade of revolutionary turmoil by 1799, making the government unstable and corrupt. Church policies were unpopular, especially since they had triggered rampant inflation. People were sick of this turmoil and longed for a more stable government that would make their lives more secure. Therefore, the interplay of military innovations that made Napoleon a national hero and the longing for a strong, secure government that Napoleon promised led to his seizure of power in 1799. Further military victories, once again against the Austrians in Italy allowed Napoleon to consolidate his hold on power and declare himself emperor of France in 1804.

While we mainly think of Napoleon as a general, he was also a very active administrator, and his internal reforms did a great deal as far as both consolidating some accomplishments of the French Revolution and suppressing others. One way to assess his government of France is to see how it conformed to the revolutionary motto: "Liberty, fraternity (i.e., nationalism), and equality". As far as political and civil liberties were concerned, Napoleon largely suppressed them with strict censorship and the establishment of a virtual police state in order to protect his power.

However, Napoleon saw equality as a politically useful concept that he could maintain with little threat to his position. After all, everyone, at least all men, were equally under his power. One of his main accomplishments as a ruler was the establishment of the Napoleonic Civil Law Codes, which made all men equal under the law while maintaining their legal power over women. Therefore, any hopes women may have had of the Revolution improving their legal position were thwarted by Napoleon.

Napoleon saw nationalism as indispensable to maintaining the loyalty of the French people to his regime. After all, it was the spirit of nationalism that had inspired its armies in a remarkable series of victories that had especially benefited Napoleon and allowed his rise to power. The trick was for Napoleon to build a personality cult around himself so that the French people would identify him with France itself and therefore make loyalty to him equivalent to loyalty to France. However, by identifying national loyalty with one man, Napoleon inadvertently weakened the inspirational force of nationalism and thus his own power.

Overall, Napoleon's internal policies strengthened France and allowed it to dominate most of Europe after a series of successful military campaigns (1805-7). Naturally, he established his style of rule in the countries he overran. However, he mistakenly thought that the administrative and legal reforms of the revolution he carried to the rest of Europe could be separated from the ideas of Nationalism and Liberalism (liberty and equality) that had given those reforms life and substance. Therefore, Napoleon's imperial rule inadvertently spread these ideas of Nationalism and Liberalism.

This had three effects, all of which combined to overthrow Napoleon. First of all, the empire's non-French subjects picked up the ideas of Nationalism and Liberalism and used them to overthrow, not support, French rule. Second, subject rulers adopted many of the very military and administrative reforms that had made France so strong. Once again, this was not to support French rule, but rather to overthrow it.

Finally, Napoleon's power and success up until 1808 apparently blinded him to his own limitations. Therefore, he got involved in a long drawn out war in Spain (1808-14) and launched a disastrous invasion of Russia (1812). This led to the formation of a new coalition that finally defeated and overthrew him in 1815. The victors met at the Congress of Vienna, hoping to restore the old order as it had existed before the Revolution.

However, despite his intentions, Napoleon had effectively planted the seeds of Nationalism and Liberalism across Europe, and these ideas would spread in new waves of revolution by mid-century. Europeans would take these ideas, along with the powerful new technologies unleashed by the Industrial Revolution, to establish colonies across the globe by 1900. Ironically, these European powers, like Napoleon, would fall victim to the force of these ideas when their subjects would use them in their own wars of liberation after World War II.

FC106AThe Rise of Napoleon (1795-1808)

Napoleon's rise to power

Napoleon's career largely resulted from the military innovations he inherited from the French Revolution, such as mass conscription which made possible the use of block tactics in order to attack in column and eliminated the need for supply lines, thus making French armies much more mobile. The Revolution also provided him with young officers who had largely developed these new tactics and were willing and able to successfully implement them on the battlefield. Therefore, the two characteristics of Napoleonic warfare, massed firepower and mobility were already present when he started his career.

Napoleon Bonaparte himself was barely French, his homeland Corsica having just become part of France two years before his birth in 1769. He attended a French military school and, while not a great student, picked things up quickly and finished a three-year program in one year. His Corsican accent and wild appearance set him apart from his classmates. Although sociable, he liked to be alone a lot. At an early age he exhibited the qualities that would earn him and France an empire: remarkable intellect, puritanical self discipline, a virtually inexhaustible energy level, and a willingness to plan things out in such detail as to leave nothing to chance. He admired Caesar, Alexander and Charlemagne and, like them, exhibited the quick decisive manner that made them all great leaders.

At age sixteen, Napoleon became a second lieutenant in the royal artillery, but his non-noble and Corsican origins left him little chance of promotion. All that changed with the French Revolution. In 1789, he went back to Corsica to fight for its independence. After quarrelling with the leader of the revolt, he returned to France and joined the Jacobins. In 1793, the young Bonaparte became a national hero by leading the recapture of the French port of Toulon from the British. The next year Napoleon's ties with the Jacobins and their fall in the Thermidorean Reaction landed him in jail for several months.

It was in 1795 that Napoleon got his big break when his famous "whiff of grapeshot" mowed down rebels in the streets of Paris and saved the new government, the Directory, from counter-revolution. This event catapulted Napoleon into the command of the Army of Italy, a ragtag army without enough shoes or even pants for its men. Nevertheless, he led this army against the Austrians in a lightning campaign that showed all the hallmarks of Napoleonic generalship: rapid movement, the ability to outnumber the enemy at strategic points with men and massed firepower, and a knack for doing the unexpected to keep his enemy constantly off balance. Napoleon drove with characteristic speed through northern Italy and then into Austria, forcing it to sign the Treaty of Campo Formio. However, this victory and the prospect of renewed French offensives alarmed kings all over Europe who formed the Second Coalition of Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia against France.

Napoleon saw Britain as his main enemy, because it funded France's other enemies and also had a powerful navy protecting its coasts. As a result, Napoleon came up with a bold, if ill conceived, plan: conquer Egypt and use it as a stepping-stone to invade British-held India. At first, all went well. Napoleon's fleet eluded the great British admiral, Lord Nelson and landed in Egypt in 1798. The French decisively beat the Mamluke army and soon ruled Egypt. Then things fell apart. Lord Nelson found the French fleet and demolished it in the Battle of the Nile, thus stranding the French army in Egypt. Napoleon tried a daring march to Istanbul by way of Syria, but his artillery was captured and he had to return to Egypt with his sick and demoralized army. While the French languished in Egypt, Napoleon got word of political turmoil in France. He thereby abandoned his army (which later surrendered to the British) and slipped across to France. He then took part in a daring plot to overthrow the government. The conspiracy succeeded and Napoleon became First Consul of France in 1799.

Consolidating his power

The government that Napoleon and his allies set up, the Consulate, was a mockery of democracy and aptly reflected the above quotation. People elected delegates who chose other delegates who chose other delegates from whom were appointed legislators who had no power anyway. So much for the legislature. As for Napoleon's fellow conspirators, Ducos and Sieyes, they were shoved into the background and forgotten within a month, leaving Napoleon firmly in charge of France. However, his position was far from secure, because France was still ringed by the Second Coalition.

Napoleon first attacked Austrian forces in northern Italy, which he barely defeated at the Battle of Marengo (1800). This victory allowed Napoleon to return to France in triumph and further consolidate his position there. Meanwhile, his generals finished up the war against Austria, taking the Austrian Netherlands, northern Italy, and the left bank of the Rhine for France.

That left Britain to face France. Since Britain's navy and France's army were virtually unbeatable by the other side, and several neutral nations including the United States and Sweden had armed themselves against both Britain and France, the two big powers made peace in 1802. Prussia and Russia soon followed suit. Peace settled over Europe, at least temporarily.

Napoleon next turned his attention to Germany in order to settle a number of land disputes. Germany was still a patchwork of secular principalities, free cities, and church states. Since the Church tended to favor Catholic Austria against revolutionary France, Napoleon eliminated all but one church state and 44 out of 50 free cities, giving their lands to various German princes who now saw Napoleon as their benefactor.

Having fought his enemies to a standstill and made France the most feared and respected power in Europe, Napoleon could now pursue his next goal: becoming emperor of France. This was a tricky situation, since the French people might not take kindly to getting a new king so soon after getting rid of the old one. Using the title of emperor rather than king would partly ease people's misgiving and also give them a sense of France's imperial superiority over the rest of Europe. Napoleon approached the title in stages, first getting himself elected consul for ten years, then for life, and then, after a fake assassination plot to make people realize how much they loved him, emperor.

The coronation in 1804 was a splendid affair with even the pope coming to crown Napoleon. (Napoleon actually decided to crown himself and just let the pope watch.) The next day the emperor gave bronze eagles to his regiments as standards reminiscent of the Roman Empire. He even created a new nobility of dukes and counts from his officers in order to make a court that rivaled the splendor of other European courts.

The rest of Europe saw Napoleon's imperial crown as part of a plan to rule all of Europe. This triggered the war of the Third Coalition of Austria, Britain, and Russia against France and Spain (1803-1807). Once again, Napoleon was faced with his old nemesis, Britain, that "nation of shopkeepers" (to quote Adam Smith) whose navy shielded them from his military might. If only the British navy could be removed, Napoleon could slip across the Channel with his army and bring Britain to its knees. His plan for removing the British fleet was to lure it to the West Indies with the combined French and Spanish fleets. This would leave the Channel open for the French to cross. However, the British commander, Nelson, guessed this plan and managed to blockade the French and Spanish fleets in the Spanish port of Cadiz. When they tried to break out, the British crushed them in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805). Britain remained safe as its navy still ruled the waves.

Seeing his failure at sea, Napoleon marched his army eastward where he met the much larger combined armies of Austria and Russia at Austerlitz. Concentrating his forces in the center, he drove through and split the Russian and Austrian armies, winning possibly the most brilliant victory of his career (1805).

Austerlitz gave Napoleon the power to declare the Holy Roman Empire defunct, making him the heir apparent of Rome's imperial grandeur. He also used this opportunity to form the Confederation of the Rhine from the German princes grateful to him for the lands he had given them before. The Confederation consisted of about half of Germany and formed a large buffer zone on France's eastern border. This upset Prussia who had been sitting on the sidelines, but now decided to join the war. However as quickly as Prussia entered the war, its forces were shattered by Napoleon's blitzkrieg (1806).

Finally, there was Russia. After a bloody indecisive battle in the snow at Eylau, Napoleon won a decisive victory at Friedland. Now he could impose his kind of peace on Europe. Negotiations between Napoleon and Czar Alexander I were conducted on a raft in the middle of the Nieman River while Frederick William III of Prussia had to await his fate along the shore. The settlement for Prussia was not kind, taking nearly half of its land and population to help carve out the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, a revived Poland that owed its existence and lasting loyalty to Napoleon. France and Russia recognized each other's spheres of influence, but France certainly emerged as the dominant power in Europe. Besides France, Napoleon directly ruled Belgium, Holland, the West Bank of the Rhine, the Papal States, and Venice. Then there were the states that were nominally free but lived under French law, administration, and usually French rulers who happened to be Napoleon's relatives: the kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Italy, Switzerland, the Confederation of the Rhine, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and Spain (after 1808). Finally, there were Napoleon's allies who had to follow him in war: Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Only Hitler ever came this close to ruling all of Europe.

The Napoleonic state

While Napoleon is mainly remembered for his military campaigns and conquests, much of his importance lies in his government of France and how it consolidated the gains of the Revolution. For one thing, he kept the Revolution's administrative reform of dividing France into 83 departements whose governors ( prefects) he appointed centrally. He centralized the tax system (still used today) and established the Bank of France to stabilize the economy of France. The Revolution's system of free but mandatory education was kept and expanded with military uniforms and discipline being imposed. Napoleon also consolidated many of the Revolution's social and legal advances into five law codes. His civil code maintained the equality of all men before the law, but reasserted the power of the husband over the wife, thus negating some of the influence women had exerted during the Revolution.

Although not a religious man, Napoleon recognized the attachment of most French people to the Catholic Church and how the Revolution's policies against the Church had caused discontent and revolts. Therefore, in 1801 he made peace with the Church, recognizing it as the religion of the majority of Frenchmen and giving the clergy the right to practice their religion within the "police regulations" of France. Those regulations kept confiscated Church lands for the state and still paid the clergy their salaries. Regardless of that, Napoleon gained a great deal of popularity through his Church policy without giving up anything of essence.

Napoleon may have consolidated some gains of the Revolution, but he repressed others, for his "police regulations" in many ways amounted to a police state. Such civil rights as freedom of speech and press were now things of the past as 62 of 73 newspapers were repressed, and all plays, posters, and public conversations had to meet strict standards of what Napoleon thought was proper. Enforcing all this was Napoleon's minister of police, Joseph Fouche, formerly one of the Jacobins' representatives on mission during the Terror. He was a slippery character who had survived the Thermidorean Reaction and attached his fortunes to those of Napoleon. Fouche's spy network (one of four in France) kept him informed on just about everyone of importance in France (including Napoleon's own personal life). Fouche himself claimed that wherever three or more people were talking, one of them was reporting to him. By 1814 he had an estimated 2500 political prisoners locked away. Napoleonic rule certainly had its darker side.

By 1808, Napoleon was at the pinnacle of power. He controlled most of Europe to some degree or other. France was tightly under control and efficiently run. But forces were converging that would bring the Napoleonic regime crashing down in ruins.

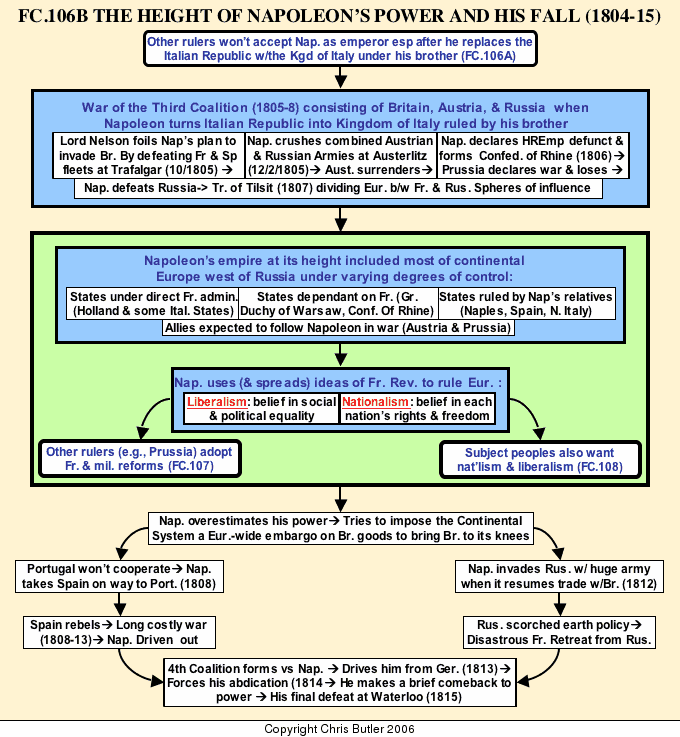

FC106BNapoleon's Years of Triumph and Fall (1800-1815)

Clear policy consists of making nations believe they are free.— Napoleon

The government that Napoleon and his allies set up, the Consulate, was a mockery of democracy and aptly reflected the above quotation. People elected delegates who chose other delegates who chose other delegates from whom were appointed legislators who had no power anyway. So much for the legislature. As for Napoleon's fellow conspirators, Ducos and Sieyes, they were shoved into the background and forgotten within a month, leaving Napoleon firmly in charge of France. However, his position was far from secure, because France was still ringed by the Second Coalition.

Napoleon first attacked Austrian forces in northern Italy, which he barely defeated at the Battle of Marengo (1800). This victory allowed Napoleon to return to France in triumph and further consolidate his position there. Meanwhile, his generals finished up the war against Austria, taking the Austrian Netherlands, northern Italy, and the left bank of the Rhine for France.

That left Britain to face France. Since Britain's navy and France's army were virtually unbeatable by the other side, and several neutral nations including the United States and Sweden had armed themselves against both Britain and France, the two big powers made peace in 1802. Prussia and Russia soon followed suit. Peace settled over Europe, at least temporarily.

Napoleon next turned his attention to Germany in order to settle a number of land disputes. Germany was still a patchwork of secular principalities, free cities, and church states. Since the Church tended to favor Catholic Austria against revolutionary France, Napoleon eliminated all but one church state and 44 out of 50 free cities, giving their lands to various German princes who now saw Napoleon as their benefactor.

Having fought his enemies to a standstill and made France the most feared and respected power in Europe, Napoleon could now pursue his next goal: becoming emperor of France. This was a tricky situation, since the French people might not take kindly to getting a new king so soon after getting rid of the old one. Using the title of emperor rather than king would partly ease people's misgiving and also give them a sense of France's imperial superiority over the rest of Europe. Napoleon approached the title in stages, first getting himself elected consul for ten years, then for life, and then, after a fake assassination plot to make people realize how much they loved him, emperor.