War & revolutionUnit 19: War and revolution in Europe (1914-20)

FC126The Causes and Outbreak of World War I

Yes, this delightful land which we inhabit and which nature caresses with love is made to be the domain of liberty and happiness...I am French, I am one of thy representatives!...Oh, sublime people! Accept the sacrifices of my whole being. Happy is the man who is born in your midst; happier is he who can die for your happiness.— Robespierre

France will have but one thought, to reconstitute her forces, gather her energy, nourish her sacred anger, raise her young generation to form an army of the whole people, to work without cease, to study the methods and skills of our enemies, to become again a great France, the France of 1792, the France of an idea with a sword. Then one day she will be irresistible. Then she will take back Alsace-Lorraine.— Victor Hugo

The lights are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.— Lord Grey

Introduction

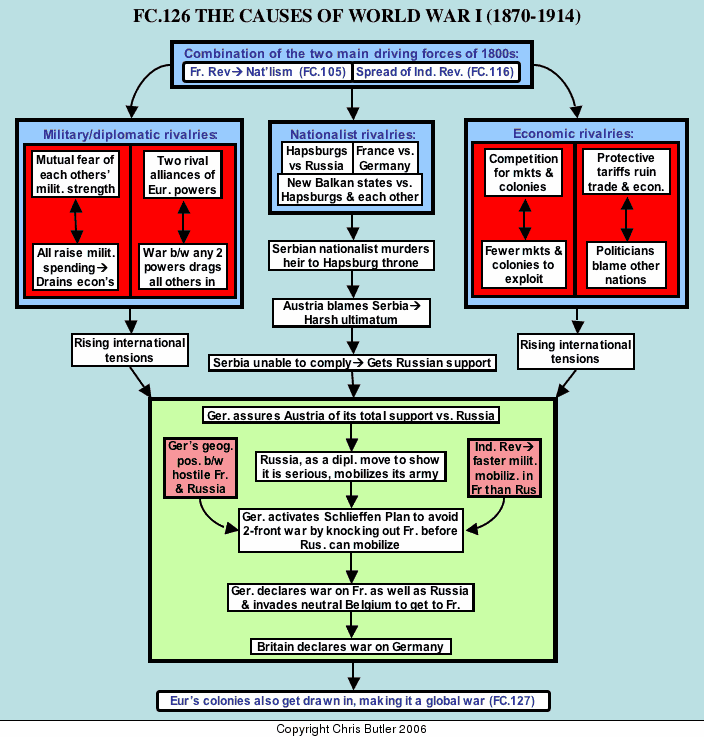

The century from 1815 to 1914 was one of the most peaceful in European history. This was largely because European powers were preoccupied with internal political events (i.e., liberal and nationalist movements) and economic developments (industrialization) which gave them the power and scope to expand their colonial empires without getting too much in each other's way. However, the same forces that kept Europe tranquil in the 1800’s also carried the seeds for trouble in the first half of the 1900's, making it a time of war, revolution, and economic turmoil.

People often cite the assassination of the Austrian archduke, Franz Ferdinand, as the cause of World War I. This is true as an immediate, short-range cause, but his murder alone could not have triggered a global war. Rather, World War I was the product of two of the most powerful forces driving European civilization in the 1800's: nationalism and industrialization. Together and separately, they would create three factors that led to war: German unification, territorial rivalries, and economic competition.

Economic competition

The spread of the Industrial Revolution outside of Britain after 1850 expanded the consumer markets available for businesses to exploit. But it also expanded the number of producers competing for those markets, triggering more competition for what seemed to be a stagnant economy by the turn of the century. Intensifying this competition in each country were fierce nationalistic feelings fostered by an expanding public school system that preached its nation's superiority over other nations and the dangers they posed to it.

European nations did two things to protect themselves. First, they (especially France, Britain, and Germany) joined in the rush for overseas colonies. However, by 1900, most good places for colonization had been taken, just causing more competition for what few areas were left. For example, Germany and France had two bitter crises that nearly led to war over control of Morocco.

The second strategy was the use of protective tariffs (import taxes) to raise the cost of foreign goods and make the home nation's goods correspondingly more appealing to its consumers. Of course, other nations did the same thing. Prices went up, trade declined, and unemployment grew, causing internal unrest and turmoil. As a result, politicians looked for scapegoats and conveniently blamed other nations. This led to more tariffs, lower trade, rising unemployment, unrest, blame, and so on.

German unification

Nationalism created other problems. The unification of Italy and especially Germany upset the balance of power in central Europe, replacing many small and vulnerable states with two unified and aggressive nations. Germany's rapid rise as a political, economic, and military giant alarmed its neighbors, particularly France, still burning to avenge its humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Nations reacted in two ways: the formation of alliances and military build-ups.

In the two decades since the Franco-Prussian War, Bismarck had masterfully juggled alliances to keep France isolated and Europe at peace. But Bismarck was fired in 1890 by the short-sighted and aggressive new Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who let Germany's alliance with Russia, which Bismarck had carefully nurtured for 30 years, lapse. France quickly seized the opportunity to ally with Russia. As in 1756 with Frederick the Great, the nightmare of a two front war fought on German soil loomed as an imminent threat.

Desperate for allies, Germany attracted Austria (Russia's vehement enemy) and Italy into what was known as the Triple Alliance. France lured Britain into its alliance, known as the Triple Entente, by playing on British fears of the growing German economy, navy, and colonial empire. With all the major powers aligned in one camp or the other, there was the serious danger that if two members of opposing alliances got into a war or crisis, all the other alliance members and their colonial empires would be dragged in, too. That is exactly what would happen in 1914.

The Industrial Revolution's rapid creation of new technologies was by no means confined to peaceful ends. New and improved weapons such as the machine gun, submarine, and steel clad battleship combined with nationalist pride and fear of other nations to trigger an arms race such as the world had never seen. As soon as one nation started building armaments, its rivals would do the same and try to outdo the first nation. This would only alarm the first power, which would further increase its armaments, and so on. Each nation acted in what it felt was self-defense, but what other nations saw as aggression.

Therefore, France built up its forces to avenge the defeat of 1870 and to protect itself against German aggression. Germany armed itself to guard against French aggression and a two front war with Russia as well. The Russian army expanded to protect itself from German aggression. And the Austrian military grew to counter Russian moves into the Balkans. To make matters worse, Wilhelm II, despite Bismarck's advice, wanted a colonial empire to match those of Britain and France. This involved building a navy, which prompted Britain to build up its navy to keep ahead of Germany. Therefore, in addition to a military arms race, Germany found itself involved in an equally expensive naval arms race as well. In the end, this expensive arms race only weakened everyone's security and economies, added to mutual fears and suspicions, and led to a general expectation of war that became a self-fulfilling prophecy as nations prepared for that war.

Territorial rivalries

already abounded among the many competing states and peoples in Europe. Fueling those rivalries were strong nationalist feelings further intensified by the ideas of Social Darwinism and militarism (the belief that there was nothing more glorious than to fight and even die for one's nation). Writings of the nineteenth century abounded with militaristic sentiments, or ideas that could be easily misinterpreted to support such sentiments. One very influential philosopher who was not so simplistically aggressive as suggested by the following quotations was Georg Wilhelm Hegel, whose ideas heavily influenced such diverse thinkers as Marx and Lenin on the one hand, and Bismarck and Hitler on the other. Hegel saw war as the great purifier, making for“...the ethical health of peoples corrupted by a long peace, as the blowing of the winds preserves the sea from the foulness which would be the result of a prolonged calm.”

“...world history is no empire of happiness. The periods of happiness are the empty pages of history because they are the periods of agreement without conflict.”

“World history occupies a higher ground...Moral claims which are irrelevant must not be brought into collision with world historical deeds or their accomplishments. The litany of private virtues—modesty, humility, philanthropy, and forbearance—must not be raised vs. them. So mighty a form [the state] must trample down many an innocent flower--crush to pieces many an object in its path.”

Another German philosopher whose ideas were oversimplified and misinterpreted was Freidrich Nietzsche.

“Ye shall love peace as a means to new war, and the short peace more than the long. You I advise not to work, but to fight. You I advise not to peace but to victory...Ye say it is the good cause which halloweth every war. I say unto you it is the good war which halloweth every cause. War and courage have done more great things than charity.”

Playing off these ideas was General von Bernhardi. His book, Germany and the Next War (1911), had such chapter titles as "The Right to Make War", "The Duty to Make War", "Germany's Historic Mission", and "World Power or Downfall" that fairly well summed up its thesis. Another German writer, Heinrich von Treitschke, like Hegel, glorified the state, but more brutishly saw its subjects as basically its slaves and declared war as the highest expression of Man.

“It does not matter what you think as long as you obey”

“...martial glory is the basis of all the political virtues; in the rich treasure of Germany's glories the Prussian military glory is a jewel as precious as the masterpieces of our poets and thinkers.

“...to play blindly with peace...has become the shame of the thought and morality of our age.”

“War is not only a practical necessity, it is a theoretical necessity, an exigency of logic. The concept of the State implies the concept of war, for the essence of the State is power...That war should ever be banished from the world is a hope not only absurd, but profoundly immoral. It would involve the atrophy of many of the essential and sublime forces of the human soul...A people which become attached to the chimerical hope of perpetual peace finishes irremediably by decaying in its proud isolation...”

Psychologically and militarily, Europe was ready for war.

There were two regional "hot spots" in Europe in 1914. First, there were Alsace and Lorraine, which France desperately wanted back from Germany since the Franco-Prussian War. Second, there was the Balkans, destabilized by numerous Slavic nationalities, with Russia posing as their champion, wanted to break loose from the Hapsburg Empire. As serious as the situation in Alsace and Lorraine was, people saw the Balkans as a disaster waiting to happen, calling it the “powder keg of Europe” which would hurl the whole continent into war. They were right.

The Road to war (June-August, 1914)

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a young member of a Serbian terrorist group known as the Black Hand, murdered the heir apparent of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife in Sarajevo, Austria. Naturally, this created quite a stir in the papers, but few at that time saw it as important enough to lead to a general war. However, behind the scenes, all the forces of nationalist rivalries, economic competition, military buildups, and interlocking alliances were blowing this murder way out of proportion and driving events wildly out of control and toward war.

Nearly a month passed before events picked up. Although there was no firm evidence that Serbia, a Slavic state bordering Austria, had anything to do with the murder, Austria still blamed it for the murder since the Black Hand was a Serbian ethnic group operating from Serbia and trying to stir up the large Serb population, against Austrian rule. With German encouragement, Austria issued severe demands to the Serbian government on July 23, saying that failure to comply with its terms would lead to war. Compliance with its harsh terms would totally humiliate Serbia. However, Russia supported Serbia and, to show it was serious about the Serbian crisis, started mobilizing its armies.

In the past, this would have been a strong, although acceptable, way of exerting diplomatic pressure, since armies and diplomacy moved slowly, giving each side time to resolve a crisis before it was too late. However, times had changed from the leisurely pace of pre-industrial wars and had drastically reduced the margin of error within which kings and diplomats had to work. Two things specifically made Russia's mobilization unacceptable: Germany's geopolitical position and railroad timetables.

As stated above, Germany's geopolitical nightmare was a two-front war. Russia's alliance with France made that a very real possibility. Since Russia refused to cancel the mobilization order, and France would not reveal if it planned to get involved if war broke out, the Germans could only assume the worst, a two front war. That brings us to the Schlieffen Plan.

The Schlieffen Plan was Germany's strategy for turning a two-front war into two successive one-front wars. It assumed that pre-industrial Russia's armies would be slow to mobilize, thereby giving Germany enough time to concentrate its forces and deliver a knockout blow against France and then concentrate its efforts on Russia.

The key to, and problem with, this plan was the precise timing of railroad timetables necessary for the rapid mobilization of Germany's armies. With Russia already mobilizing, Germany felt compelled to put the Schlieffen Plan into action before it was too late. However, that required war with France, so Germany, with no apparent provocation, declared war on France as well as Russia. That left the question of what Britain would do, which brings us back to the Schlieffen Plan.

Germany's high command considered the terrain and string of French fortresses along its western border with France too difficult for launching a quick offensive. The best route lay through the open low country of Belgium. However, Belgium refused passage to German armies, and so Germany, driven by the strict timetable of the Schlieffen Plan, violated Belgian neutrality in order to crush France and stay on schedule. Britain, outraged by this act, declared war on Germany.

And so Europe, dragging its worldwide colonial empires in its wake, blundered into World War I. Not that everyone saw it in such negative terms. Crowds all over Europe greeted the news jubilantly. Most men saw their nation as superior to all others and expected a quick victory much like that won by Prussia in 1870. Each nation's army would occupy the enemy's capital by Christmas, which meant that anyone not enlisting now would miss out on all the fun and glory. Little did they suspect the scope of the disaster about to befall them over the next four years.

FC127Total War (1914-1918)

At first there will be increased slaughter--increased slaughter on so terrible a scale as to render it impossible to get troops to push the battle to a decisive issue. They will try to, thinking that they are fighting under the old conditions, & they will learn such a lesson that they will abandon the attempt forever. Then...we shall have...a long period of continually increasing upon the resources of the combatants...Everybody will be entrenched in the next war.— I.S. Bloch (1897)

You smug faced crowds with kindling eye Who cheer when soldier lads march by Sneak home and pray you'll never know The hell where youth and laughter go.— Siegfried Sassoon

We are ready, and the sooner the better for us.— German General von Moltke

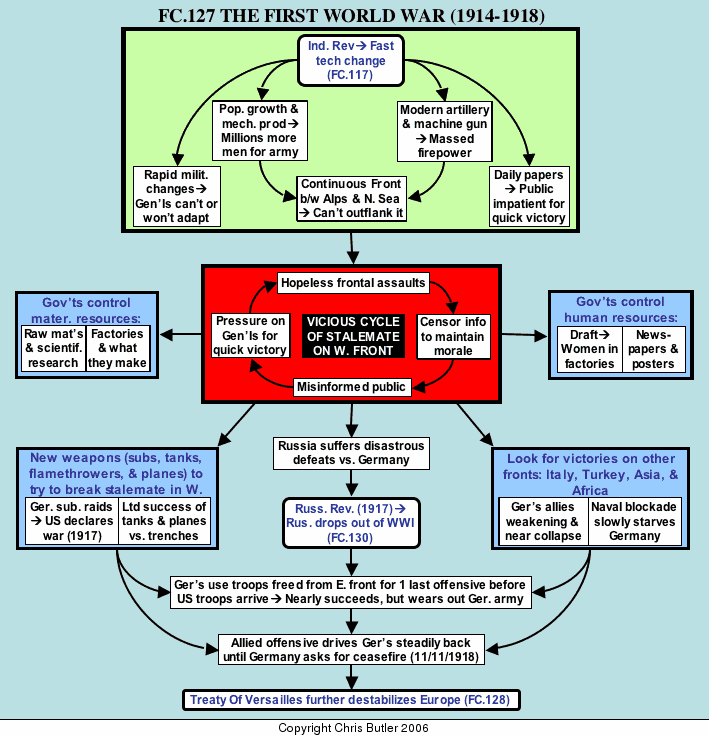

The war of movement (August-September, 1914)

When Europe went to war in 1914, many, although not all, people welcomed it as an opportunity for national glory. Soldiers, especially in Western Europe, also marched, or rather rolled, to war much more quickly than ever before. France alone, with its extensive network of railroads, had 7000 trains, some only eight minutes apart, moving troops to the front. Also, rapid population growth and mechanization from the Industrial Revolution, freed many more men than ever before for war.

Europe also marched to war better armed by far than any previous army in history. Germany seemed particularly armed to the teeth, thanks to the Kruppworks at Essen, Germany, a vast complex of 60 factories with its own police force, fire department, and traffic laws. One new weapon would especially change the face of war. That was the machine gun, which could fire 600 bullets per minute and stop any old-style human wave assaults dead in their tracks, literally. It was the machine gun that would put an end to the illusion of a quick victory in a war of movement--but not at first.

In the opening weeks, the Schlieffen Plan went like clockwork. While stopping a French offensive, known as Plan 17, from driving eastward into Germany, the strong German right flank swept the French, British, and Belgian forces back toward Paris, covering up to 20 miles a day, an exhausting pace for infantry loaded with up to 60 pounds of equipment. In fact, that pace plus the German General von Moltke's weakening of the Western offensive in order to meet a Russian offensive unexpectedly materializing in the East may have doomed the Schlieffen Plan to failure. The French and British allies made their stand to save Paris along the Marne River, many troops being rushed to the front in Paris taxicabs. The allies stood fast and the German offensive ground to a halt. Then, somewhat spontaneously and out of simple survival instinct, the soldiers started digging trenches. The Schlieffen Plan and war of movement had failed. The age of trench warfare had begun along what would ever after be remembered as the Western Front.

The new face of war

Making trench warfare especially bad was the fact that the opposing trenches were generally only 500 yards or less apart. This kept soldiers in constant contact with the enemy and constantly immobilized in the mud trenches to avoid the danger above. This contrasted sharply with previous wars where armies would fight a battle, withdraw, and then regroup for several weeks or months before the next battle. This had given soldiers long breaks from the terrors of battle, a psychological safety net that kept them halfway sane. But that safety net no longer existed as soldiers stayed in constant contact with the enemy and became worn out from battle fatigue, producing a catatonic-like state known popularly as the "thousand yard stare".

Life in the trenches, even during relative lulls in the fighting, was a thoroughly wretched experience. It was hot in summer and especially cold in winter. It was also wet and muddy, giving the soldiers little or no chance to bathe, exposing them to infestations of rats, lice, disease, and infection. One of the worst of these infections was trenchfoot, caused by the soldiers' not being able to remove their socks and boots for long periods of time and often resulting in amputation of the infected foot or leg. The following excerpts from the novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, by Eric Maria Remarque, himself a veteran of the war, capture the misery of life in the trenches.

There are rumors of an offensive. We go up to the front two days earlier than usual. On the way, we pass a shelled schoolhouse. Stacked up against its longer side is a high double wall of yellow, unpolished brand-new coffins. They still smell of fir, and pine, and the forest. There are at least a hundred.

“That's a good preparation for the offensive," says Muller astonished.

“They're for us," growls Detering.

“Don't talk rot" says Kat to him angrily.

“You be thankful if you get so much as a coffin," grins Tjaden, "they'll slip you a waterproof sheet for your old Aunt Sally of a carcass.”

The others jest too, unpleasant jests, but what else can a man do?---The coffins are really for us. The organization surpasses itself in that kind of thing...

We are in low spirits. After we have been in the dug-outs two hours our own shells begin to fall in the trench. This is the third time in four weeks. If it were simply a mistake in aim no one would say anything, but the truth is that the barrels are worn out. The shots are often so uncertain that they land within our own lines. Tonight two of our men were wounded by them.

******

The front is a cage in which we must await fearfully whatever may happen. We lie under the network of arching shells and live in a suspense of uncertainty. Over us Chance hovers. If a shot comes, we can duck, that is all; we neither know nor can determine where it will fall.

It is this Chance that makes us indifferent. A few months ago I was sitting in a dugout playing skat; after a while I stood up and went to visit some friends in another dugout. On my return nothing more was to be seen of the first one, it had been blown to pieces by a direct hit. I went back to the second and arrived just in time to lend a hand digging it out. In the interval it had been buried

It is just as much a matter of chance that I am still alive as that I might have been hit. In a bomb-proof dugout I may be smashed to atoms and in the open may survive ten hours' bombardment unscathed. No soldier outlives a thousand chances. But every soldier believes in Chance and trusts his luck.

******

We must look out for our bread. The rats have become much more numerous lately because the trenches are no longer in good condition. Detering says it is a sure sign of a coming bombardment.

The rats here are particularly repulsive, they are so fat-- the kind we call corpse rats. They have shocking, evil, naked faces, and it is nauseating to see their long, nude tails.

They seem to be mighty hungry. Almost every man has had his bread gnawed. Kropp wrapped his in his waterproof sheet and put it under his head, but he cannot sleep because they run over his face to get at it. Detering meant to outwit them: he fastened a thin wire to the roof and suspended his bread from it. During the night when he switched on his pocket-torch he saw the wire swinging to and fro. On the bread was riding a fat rat.

At last we put a stop to it. We cannot afford to throw the bread away, because already we have practically nothing left to eat in the morning, so we carefully cut off the bits of bread that the animals have gnawed.

The slices we cut off are heaped together in the middle of the floor. Each man takes out his spade and lies down prepared to strike. Detering, Kropp, and Kat hold their pocket-lamps ready.

After a few minutes we hear the first shuffling and tugging. It grows, now it is the sound of many little feet. Then the torches switch on and every man strikes at the heap, which scatters with a rush. The result is good. We toss the bits of rat over the parapet and again lie in wait.

Several times we repeat the process. At last the beasts get wise to it, or perhaps they have scented the blood. They return no more. Nevertheless, before the morning the remainder of the bread on the floor has been carried off.

In the adjoining sector they attacked two large cats and a dog, bit them to death and devoured them.

Next day there is an issue of Edamer cheese. Each man gets almost a quarter of a cheese. In one way that is all to the good, For Edamer is tasty--but in another way it is vile, because the fat red balls have long been a sign of a bad time coming. Our forebodings increase as rum is served out. We drink it of course; but are not greatly comforted.

For days we loaf about and make war on the rats. Ammunition and hand-grenades become more plentiful. We even overhaul the bayonets--that is to say, the ones that have a saw on the blunt edge. If the fellows over there catch a man with one of those he's killed at sight. In the next sector some of our men were found whose noses were cut off and the eyes poked out with their own saw-bayonets. Their mouths and noses were stuffed with sawdust so that they suffocated. Some of the recruits have bayonets of this kind; we take them away and give them the ordinary kind.

But the bayonet has practically lost its importance. It is usually the fashion now to charge with bombs and spades only. The sharpened spade is more handy and many-sided weapon; not only can it be used for jabbing a man under the chin, but is much better for striking with because of its greater weight; and if one hits between the neck and shoulder it easily cleaves as far down as the chest. The bayonet frequently jams on the thrust and then a man has to kick hard on the other fellow's belly to pull it out again; and in the interval he may easily get one himself. And what's more, the blade often gets broken off.

Total War

Four factors, all arising from the Industrial Revolution, had totally changed the face of war. First of all, the Industrial Revolution provided enough men (thanks to population growth and the mechanization of many jobs) and firepower (especially the machine gun) to dig and fill opposing trench systems stretching from the Alps to the North Sea, a system several hundred miles in length. The result was the continuous front which neither side could outflank since it was hemmed in by mountains and sea. Unfortunately, the machine gun and faster loading rifle which made the continuous front possible also made the technology of defense superior to that of offense. There was no way that unshielded infantry could get across that murderous area of flying metal known as No Man's Land. That is not to say that people did not try. They did, and with disastrous results.

Third, most generals either did not understand the nature of this new type of warfare or felt they could not afford to accept it. After all, most of these generals, many of whom were quite old, had not been able or willing to keep up on the rapidly changing technological changes transforming warfare in recent years. It is often said that generals are always fighting the last war, and nowhere did this better apply than to the generals of World War I. Before we become too critical, however, it should be pointed out that at no time in history had warfare been so thoroughly revolutionized in so short a time. The machine gun and continuous front had created a whole new ball game, but no one had a rule book by which to play. And so for four years, the generals just fumbled around the best they could while soldiers continued to die.

The fourth factor, also resulting from the Industrial Revolution and complicating matters further, was the media, in particular the newspapers. Never before had the public back home been so well informed about the progress, or lack of it, in a war. The generals had promised a quick victory, and the public and press had a close eye on how well they were doing. In the more democratic countries of France and Britain the generals found themselves under severe pressure by the public and politicians to win the war decisively and quickly. This was especially true of France, since the German lines contained northern France along with the bulk of its industries, and the French public was clamoring to get it back.

All of these factors combined to create a tragic pattern of suicidal frontal assaults that would prolong the stalemate. The casualties would be so horrible that governments modified or censored news coming from the front. This created a misinformed public and media that, thinking victory was within their grasp, would put more pressure on the generals for a quick victory. As a result, there would be more disastrous offensives more censorship to misinform the public, and so on.

Such offensives were usually conceived by generals behind the lines without any clear idea of what the front was really like. Preceding the attack for several days would be a massive bombardment that did a lot less damage than hoped for and which also told the enemy where the attack was coming. As soon as the shelling stopped, the troops went "over the top" into No Man's Land where the obstacles of barbed wire (left undestroyed by the bombardment) and craters (actually created by the bombardment) held them up so that the enemy machine guns (also unharmed since they had been taken to the dugouts below during the shelling) could cut them down. The men who suffered through this living hell often give us its most graphic and poignant descriptions.

“We listen for an eternity to the iron sledgehammers beating on our trench. Percussion and time fuses, 105's, 150's, 210's—all the calibers. Amid this tempest of ruin we instantly recognize the shell that is coming to bury us. As soon as we pick out its dismal howl we look at each other in agony. All curled and shriveled up we crouch under the very weight of its breath. Our helmets clang together, we stagger about like drunks. The beams tremble, a cloud of choking smoke fills the dugout, the candles go out.” — Verdun veteran, 1916

“the ruddy clouds of brick-dust hang over the shelled villages by day and at night the eastern horizon roars and bubbles with light. And everywhere in these desolate places I see the faces and figures of enslaved men, the marching columns pearl-hued with chalky dust on the sweat of their heavy drab clothes; the files of carrying parties laden and staggering in the flickering moonlight of gunfire; the "waves" of assaulting troops lying silent and pale on the tapelines of the jumping-off places

“I crouch with them while the steel glacier rushing by just overhead scrapes away every syllable, every fragment of a message bawled in my ear...I go forward with them...up and down across ground like a huge ruined honeycomb, and my wave melts away, and the second wave comes up, and also melts away, and then the third wave merges into the remnants of the others, and we begin to run forward to catch up with the barrage, gasping and sweating, in bunches, anyhow, every bit of the months of drill and rehearsal forgotten.

“We come to the wire that is uncut, and beyond we see gray coal-scuttle helmets bobbing about...and the loud crackling of machine-guns changes as to a screeching of steam being blown off by a hundred engines, and soon no one is left standing. An hour later our guns are "back on the first objective," and the brigade, with all its hopes and beliefs, has found its grave on those northern slopes of the Somme battlefield.” — Henry Williamson, age 19

“Verdun transformed men's souls. Whoever floundered through this morass full of the shrieking and dying...had passed the last frontier of life, and henceforth bore deep within him the leaden memory of a place that lies between life and death.” — Verdun veteran

The first day's butchery in an offensive, such as the 60,000 British who fell on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, should have been enough to convince the generals to call off the attack. But that would be admitting failure for all their months of plans and preparations. Therefore, the offensives continued, in some cases for months, with the casualties piling up into the hundreds of thousands. Each successive battle followed the same pattern and would continue that way until someone figured out how to solve the problems that the machine gun and continuous front had created. Until that day, it remained stalemate on the Western Front.

New fronts and new weapons

The continuing cycle of stalemate on the Western Front forced the warring powers to realize modern war is total war, demanding activities in all possible directions to sustain their own efforts and wear down those of the enemy. This led to efforts in five areas: control of material resources at home, control of human resources (including the media and morale), continued attempts to break through on the Eastern Front, the search for victory by opening new fronts, thus making it truly a world war, and the search for victory through the development and use of new weapons.

Material and human resources on the home front

World War I devoured enormous amounts of material resources, forcing governments to closely control production and distribution of those resources. Blockaded Germany, in particular, had to ration food strictly. It also controlled mineral resources and even scientific research, which developed synthetic nutrients and ways to derive nitrates from the atmosphere for explosives. France also had to exert strong central control over production, since its industrial north was largely behind German lines, forcing it to rebuild much of its industry further south by 1918.

Human resources had to be controlled to ensure enough men for the front and a labor force for the strategic industries at home. With so many men gone to war, women entered the work place in unprecedented numbers, taking over many occupations previously reserved solely for men before the war, such as secretaries. After the war, when many husbands and fiancées did not return, many women stayed in the workplace, giving them more economic power and eventually the vote. To maintain morale, governments assumed more control of the media, limiting or distorting the information available to the press and public. Governments also actively tried to harness popular support for the war with brightly colored and illustrated posters that glorified the war effort and portrayed the enemy as less than human.

As the homefront became more of an integral part of the total war effort, governments saw enemy factories and civilians as legitimate war targets. In 1915, a German Zeppelin launched a bombing raid on London, killing several people. Although the damage from this raid was small by later standards, it pointed the way for much worse to come for civilians in wartime.

The Eastern Front

Allied hopes for a quick Russian victory in the East were quickly dashed in August 1914 when the Germans annihilated invading Russian forces at Tannenburg. (This was the first and only time allied forces set foot on German soil during the war.) Germany also bolstered Austria against the Russians in the south, causing a much looser version of the Western Front to evolve in the East, since the armies (except Germany's) were less mechanized and thus less successful in stopping a war of movement. The Russians were particularly poorly armed (many of them even without rifles), and their offensives against the German positions met with especially disastrous results. By 1917, Russia, bled white by the war, stood on the verge of revolution.

New Fronts

Each side also tried to divert and drain the enemy's strength by opening up new fronts. Turkey was the first new power to enter the war, in this case, on Germany's side. This threatened to cut off British and French supplies to Russia by way of the Black Sea and prompted a British offensive known as the Gallipoli Campaign. This was one of the worst run operations of the war. At least twice, the British generals had victory within their grasp, but chose to nap or have teatime rather than press their advantage, giving the Turks time to bolster their line. For several months, the allies were pinned down to the beaches until disease and casualties forced them to withdraw.

After this, the main British strategy against the Turks was to stir up and support rebellions. In that regard, one of the most celebrated figures of the war was T.E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, a charismatic figure who succeeded in organizing the Arabs and destabilizing the already decrepit Ottoman Empire. The British issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which promised a Palestinian homeland for the Jews in return for their help. This promise, in conjunction with conflicting promises to the Arabs, would be (and still is) the source of intense conflict in the Middle East.

Italy, despite being part of the Triple Alliance, joined France and Britain in order to take disputed lands from Austria. However, Austria managed to defeat Italy, making it more of a burden to Britain and France, who had to keep it supplied with guns, money, and fuel just to keep it in the war. Meanwhile, Bulgaria joined Germany and Austria in order to take Macedonia from Serbia, which it accomplished quickly. Serbia's British and French allies responded by landing 500,000 men at Salonika, Greece, where they did nothing until 1918, earning it the title of Germany's "biggest internment camp."

Europe's African and Asian colonies were also dragged into the war, making it a truly global war. The British were able to seize Germany's African colonies except for German East Africa. In Asia, the Allies persuaded Japan to attack German holdings and spheres of influence in China. This gave Japan a foothold in China that it would expand in the 1930's, laying the foundations for World War II in Asia. Overall, despite mixed results, Germany's allies gradually weakened as the war dragged on.

There was also the naval front. In the years preceding the war, Germany had built a fleet second only to Britain's. In 1915, the two navies clashed at Jutland. It was an indecisive battle, with Germany getting a slight advantage. But the Kaiser, not wishing to damage his nice new navy, called it into port where the British kept it blockaded for the rest of the war. The blockade was soon extended to all German ports and slowly starved Germany to death.

New Weapons

Meanwhile, each side looked desperately for new weapons to solve the problem of the continuous front. Poison gas and flame-throwers, pioneered by Germany, became all too common and horrible features in trench warfare, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. After the war, the Geneva Convention outlawed both weapons as inhumane. However, two other weapons had a big future in warfare. One was the tank, which gained the allies at least limited success in breaking through enemy trenches. Despite their slowness (3 mph) and unreliability (only half making it to the starting line in their first major battle), tanks shielded allied troops, helping them cross No Man's Land with relatively few casualties.

The airplane, first used for observations of enemy lines, was adapted to combat use, being armed with a machine gun to shoot down other planes. At first, aerial warfare consisted mainly of individual combats (dogfights) between pilots. It was very limited, polite (at least by warfare's standards), and the most glorified aspect of World War I, a sort of chivalry in the skies. Even that changed by war's end, with the allies sending up hundreds of planes to sweep the skies and strafe and bomb the German lines, a strategy that would be developed with much more deadly effect for the next war.

The submarine was Germany's great equalizer in the naval war. While Britain ruled the waves after Jutland, German U-boats (submarines) could still lurk beneath the waves and prey upon allied shipping in retaliation for the blockade on Germany. However, some of the ships Germany sank were from the United States, technically a neutral power but actively trading much needed food and other supplies to France and Britain. While Germany felt justified in sinking any ships supplying its enemies, the United States saw these attacks on its ships as barbaric and unprovoked acts of aggression.

Germany eased up on its attacks for a while to keep America neutral. But in 1917, as the war effort got more desperate, U-boat raids resumed. Then the British intercepted and publicized the Zimmerman Telegram, in which Germany offered Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California to Mexico if it would attack the United States and divert its attention from the war in Europe. American public opinion was outraged, and the United States declared war on Germany in March 1917. That same month another ally, Russia, after three years of defeats and shortages, became engulfed in Revolution.

The end of the "war to end all wars" (1917-18)

Alexander Kerensky's moderate government that replaced the Czar, needing to look legitimate to the outside world, kept Russia in the war, which only weakened it further and led to its overthrow by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in November, 1917. The following March, Lenin signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, taking Russia out of the war while giving up Poland, Ukraine, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Finland. This also freed one million German troops for the Western Front. The question was: Could the addition of the United States compensate for the loss of Russia?

With virtually no standing army when it declared war in 1917, the United States needed a year to mobilize its industrial and military might. Therefore, in 1918, the war became a race to see who could first arrive on the Western Front in force: the newly mobilizing Americans or the Germans freed from the Eastern Front.

At first, the Germans won the race and launched an offensive, attacking with smaller tactical units to punch holes in the enemy lines and drive them back bit by bit. Also, the attacks were not preceded by artillery bombardments that could warn the enemy where the attack was coming. This strategy succeeded in driving the allies back toward Paris. But, as in 1914, the allies, now bolstered by newly arrived American units, stopped the Germans at the Second Battle of the Marne.

Now the allies went on the offensive. Using the very tactics the Germans had just used, the growing numbers of fresh American troops at their disposal and large numbers of tanks to shield their soldiers crossing No Man's Land, they sent the Germans reeling back step by step toward Germany. At the same time, the British blockade was gradually starving the German homeland to the limits of its endurance.

At this point, all the pressures building elsewhere caved in on Germany, as its allies collapsed one by one: first Bulgaria, then Turkey, and finally Austria. Exposed to attack from the south and east, Germany finally asked for an armistice (ceasefire). On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, after one final flurry of artillery fire, the guns fell silent. Here and there, opposing soldiers met in No Man's Land to pay their respects to men who, like themselves, just happened to be wearing different uniforms, and then turned toward home. The First World War was over. However, its effects would be long-lasting and varied, including the Second World War a mere twenty-one years later.

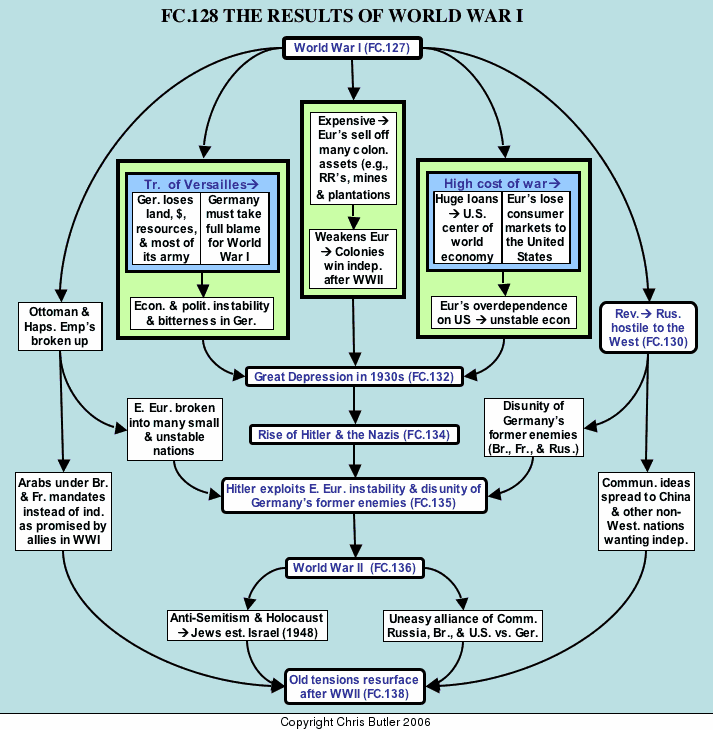

FC128The Results of World War I

Introduction

At 11:00 A.M., on November 11, 1918, World War I ended. The price it had exacted in lives and material was staggering: 37.5 million casualties, 8.5 million deaths, and $300 billion (not adjusted for modern inflation) in damages. People referred to a "lost generation" that never survived to come of age and take their turn in leading their nations. And indeed, the leaders of the next war, World War II, were largely from the same generation that had blundered into World War I.

When the guns fell silent, there were jubilant celebrations by huge crowds expecting life to return to the normal conditions that had existed before the war. However, World War I was like a severe earthquake with devastating aftershocks, leaving the edifice of European economic and political power badly cracked and in no shape for another such jolt that might bring it tumbling down. The results of World War I were varied, far reaching, and interlocking. However, they followed five main lines of development: one of them being concerned with the effects on Europe's colonies, two concerning Western Europe (economic effects and the Treaty of Versailles), and two concerned with Eastern Europe (the Russian Revolution and the collapse of the Hapsburg and Ottoman Empires).

Europe's colonies

World War I had been extremely expensive for the European powers. As a result, they sold many of their colonial mines and plantations for the cash needed to fight the war. This weakened Europe's colonial empires and set the stage for eventual liberation after the next big jolt to Europe's power: World War II.

Western Europe

was affected in two ways: the peace settlement and the economic cost of the war. First, there was the question of what sort of peace to impose on Germany. Among the leaders at the peace conference held at Versailles was President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, whose presence symbolized America's growing role as a major power in world politics. Wilson, whose country had suffered little from the war, wanted leniency for Germany along with national self-determination for all nations and a League of Nations to safeguard the international peace. However, many leaders had to justify the senseless carnage of the past four years to voters back home who wanted revenge for their sufferings of the past four years. This was especially true for France, on whose soil the war had been fought. Therefore, amid much bickering that settled nothing, the prevailing attitude that emerged was that someone must be made the scapegoat and pay for the war. And that someone was Germany.The resulting Treaty of Versailles (1919) punished Germany materially and politically. Germany lost 13.1% of its pre-war territory, including Alsace, Lorraine, and the so-called Polish Corridor, a strip of land separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Its army was limited to 100,000 men and its navy to twelve ships. (The Germans scuttled their fleet rather than let it fall into British hands.) Germany could have no submarines, air force, heavy artillery, tanks, or even a professional general staff. It lost most of its merchant marine, one-quarter of its fishing fleet and a good part of its railroad rolling stock. Each year it had to build 200,000 tons of shipping for the victorious allies and also make deliveries of other commodities such as coal and telephone poles. The final indemnity forced from Germany amounted to $32 billion (not adjusted for inflation). Germany also had to agree to the War Guilt Clause, according to which it accepted full responsibility for the war.

The German people were furious but, for the time being, helpless to do anything but sign the treaty. However, the Treaty of Versailles remained fixed in German minds as an injustice that must be avenged, especially since it destabilized their economy and helped lead to the Great Depression in the 1930's. This in turn opened the way for the rise of Hitler and the Nazis who started World War II.

Economically, World War I had been horribly expensive, both in its immediate cost to fight and its long-range effects on Europe's industries. In addition to selling colonial holdings, the allies had resorted to borrowing heavily, especially from the United States. By the war's end, European countries owed the United States $7 billion. By 1922, it would be $11.6 billion. Thanks largely to World War I, the center of world finance was shifting from London to New York City. However, the economic effects of the war went far beyond borrowing money.

For four years, European countries had been producing guns and ammunition instead of consumer goods. This had allowed other countries, the United States in particular, to take over many consumer markets from the Europeans who were preoccupied with the war. Not surprisingly, the Americans did not willingly give up these markets to the Europeans after the war. Because of this and the huge war debts, the United States became the premier economic power of the world, creating a heavy dependency on the American economy. This, combined with German instability, made the world economy vulnerable to a worldwide depression when the American economy crashed in the 1930's. And, as discussed above, that would help lead to the rise of the Nazis and World War II.

Eastern Europe

World War I also catalyzed the Russian Revolution along with the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire in South-eastern Europe. In each case, these events would destabilize their respective regions and lead to future conflicts.

The break-ups of the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires created problems in two ways. In accordance with the principle of national self-determination, the Hapsburg Empire was broken up into four new democratic nation states: Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, while Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Finland were formed from parts of the old Czarist empire. In addition there were still the various Balkan states whose squabbles had triggered World War I in the first place. While democratic in form, these new nations generally had little economic strength or history of democracy (both requiring a healthy middle class) on which to base strong democracies. Therefore, Eastern Europe was a patchwork of unstable states, providing Hitler ample opportunity for aggression that would start the Second World War. This instability along with World War II also provided fertile ground for growing anti-Semitic feelings that caused growing numbers of Jews to move to Palestine.

The break-up of the Ottoman Empire also profoundly affected the present day situation in the Middle East. The Arabs, instead of gaining their freedom for helping the allies against the Turks, as they were led to believe would happen, passed under French and British control as mandates to be prepared for independence in the future. This created a good deal of bitterness, made worse by the Balfour Declaration (1917) which had promised the Jews a homeland in Palestine for helping the allied cause. The influx of Jewish settlers into Palestine after Nazi persecution during World War II only made that bitterness worse in the Cold War period following the defeat of Germany.

The Russian Revolution which replaced a corrupt Czarist Russia with a strong communist state, the Soviet Union, created problems in two ways. First, the hostility it generated between itself and the capitalist democracies of the West undermined any joint efforts to contain future German aggression. With the old Triple Entente threatening Germany from east and west broken, Hitler could feel freer to expand eastward in the 1930's, thus providing another catalyst for the Second World War.

World War II would eventually cause a reunion of the old alliance of Russia and the West to crush the Nazis. However, it was an uneasy alliance that would come apart in the Cold War after 1945. The Russian Revolution would also lead to the spread of communism to China and other non-industrialized nations, contributing still further to the tensions of the Cold War.

As the 1920's progressed, the world seemed to be settling down to the normalcy longed for so much since 1914. Russia withdrew into itself to complete its revolution. Germany, propped up by American loans, seemed to have stabilized. And Europe overall seemed to have recovered its prosperity and maintained control of its colonies. However, World War I unleashed unseen forces that would surface with cataclysmic effect to trigger a worldwide depression and World War II.

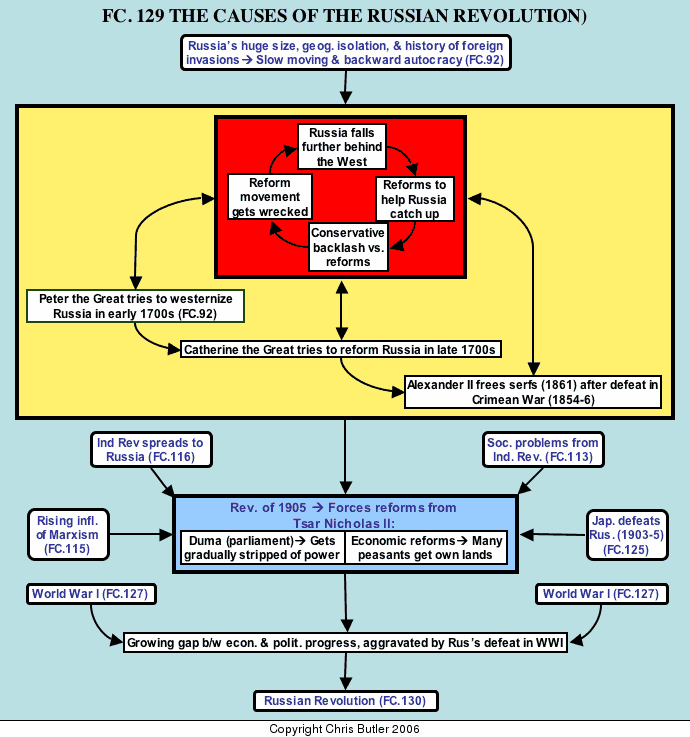

FC129Background to the Russian Revolution

Causes and background

One of the most startling and far-reaching results of the First World War was the Russian Revolution. Not only did it affect the largest nation on earth, it also had a huge impact on the rest of the world, helping lead to both World War II and the Cold War following it. While World War I may have triggered this Revolution, its roots go much further back into its history and geography in two ways.

First of all, Russia's flat and open terrain made it vulnerable to invasions that forced the Russian Czars to develop a strong absolutist state in self-defense. Second, Russia's huge size, northerly location, and isolation from Europe kept Russia cut off from the mainstream of political, economic and technological developments taking place in Western Europe. Therefore, Russia's geography and history made it a slow moving, autocratic, and backward giant that was constantly falling behind the more advanced societies in the West.

This triggered a vicious cycle of reforms to catch up with the West, a conservative backlash against the reforms, Russia falling further behind the West, more reforms, and so on. Unfortunately, not all Russians felt the West was worth copying. This led to a conservative backlash that would wreck the reforms, causing Russia to fall further behind, and so on. Peter the Great in the early 1700's, Catherine the Great in the later 1700's, Alexander I in the early 1800's, and Alexander II in the mid 1800's' all tried, or at least espoused, the cause of reform which led to conservative backlashes and the cycle repeating. That struggle is still going on in Russia today.

By the 1890s Russians could no longer ignore the forces of industrialization transforming the rest of Europe and leaving it further and further behind. Therefore, reformers targeted Russia's repressive government that used secret police to track down socialist dissidents, its backward social structure that kept the peasants in virtual, if not legal, serfdom, and its equally backward economy just starting to industrialize. Two other factors also pushed Russia toward change. One was the rising popularity of socialism. A more immediate catalyst for change was Russia's humiliating defeat in a war with Japan (1903-5) that dramatized Russia's backwardness.

All this set off the Revolution of 1905, which took Czar Nicholas II by surprise and forced him to agree to both political and economic reforms. The main political reform was the establishment of a Duma (parliament), which attempted to turn the Czar's absolute government into a constitutional monarchy. However, once the revolution settled down, the czar did all he could to crush and eliminate the Duma. Nevertheless, the Duma, however limited in power, persisted in being a voice for reform even as political repression reasserted itself.

At the same time, substantial economic reforms were taking place. The Czar's chief minister, Peter Stolypin, pushed through reforms that distributed land to some two million peasants. This gave peasants an incentive to produce more, and, by World War I, 75% of Russia's crops were going to market, with 40% of those crops going abroad. This, combined with Russia's political repression, created a gap between its economic progress and political backwardness. All that was needed was a catalyst to trigger a full-scale revolution. That catalyst was World War I.

ManyRussians, like other Europeans, greeted war jubilantly in 1914, sure that they would win a quick and glorious victory. In fact, Russia was poorly prepared for war. Its troops, although brave, were barely trained, poorly equipped (many not even having rifles), and incompetently led. Their war minister boasted of not having read a new book on military tactics in twenty-five years. As a result, Russian armies met with one disaster after another. Aggravating the situation was the Czar, Nicholas II, a weak willed man who was controlled by his wife, the Tsarina. She herself was German born and of suspect loyalty as far as many Russians were concerned. She was also under the spell of Rasputin, a drunken, semi-literate Siberian peasant posing as a monk. He did have the apparent ability to control the bleeding of the crown prince, who was a hemophiliac, along with an apparent hypnotic power over women. While scandal reigned at court (at least until Rasputin was murdered), Nicholas took personal command of the war effort, with catastrophic results.

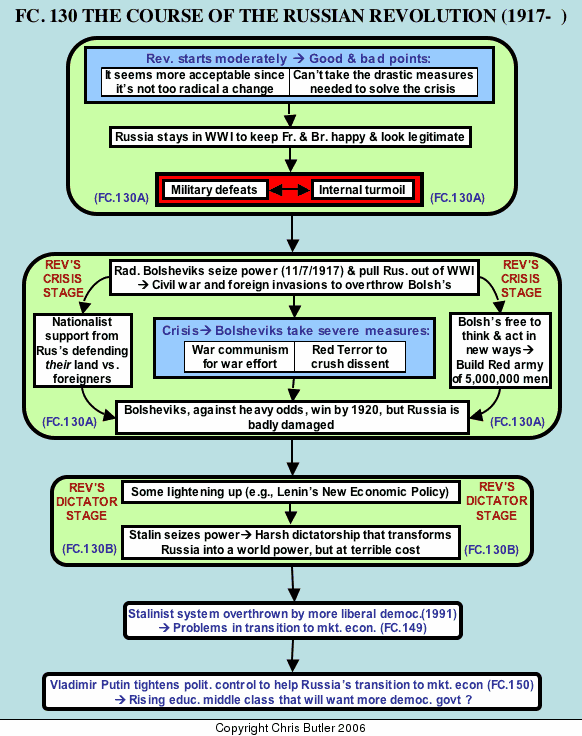

FC130The General Course of the Russian Revolution

Introduction

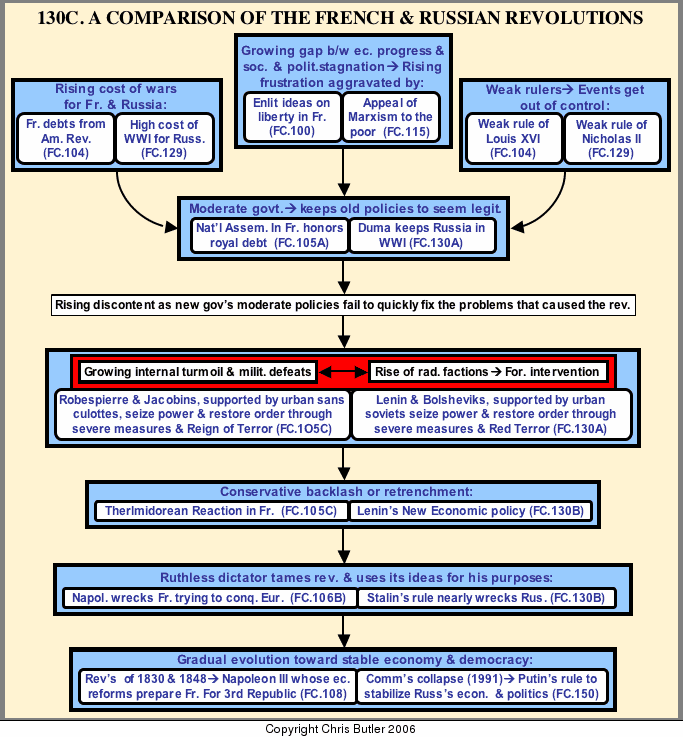

As indicated in the discussion of the French Revolution, there is a logical and long-range pattern that revolutions follow. Therefore, understanding the pattern of past revolutions can help us anticipate events in current revolutions, more specifically the final stages of the process now taking place in Russia and China. One word of caution, however: these are likely trends, not absolute certainties. Outside events (e.g., a major war) and other historical forces unique to Russia and China respectively, could divert events in a very different direction from what is indicated here. Still, this pattern generally holds up and should serve as a guide in how we deal with nations still undergoing this process. That being said, following is a comparison of the French Revolution, which after 82 years finally reached a stable democratic form of government by 1871, and the Russian Revolution, which after 92 years is presumably in its final stage of evolution toward democracy.

Forces leading to revolution

Both countries shared three elements that helped lead to war:

1) Both regimes were burdened by heavy debts incurred from wars. In France’s case, this was the debt incurred by its support of the American Revolution. For Russia, this was the even higher cost in lives and money suffered during the first three years of World War I.

2) In each country, there was a growing gap between economic progress and social and political stagnation. For the French this was the continued prominence and privileges of the noble class as opposed to the more liberal ideas and progressive economic practices of the middle class. For Russia, this largely came from the peasantry, whose economic progress from Peter Stolypin’s agrarian reforms contrasted with the repressive rights and privileges of the nobles. In each case new political ideas aggravated these frustrations. In France these were the ideas of Enlightenment philosophes such as Rousseau and Voltaire. In Russia it was Marxism.

3) Both countries had weak leaders who let events get quickly out of control. In France and Russia respectively, these were Louis XVI and Nicholas II.

The early stages of revolution

Both revolutions started out with moderate regimes that kept one or more of the old regimes’ policies to maintain the look of continuity and legitimacy. In France, that government was the National Assembly, which kept the king as a figurehead and honored the royal debt. In Russia, it was the Duma, which kept Russia in World War I. In both cases these policies just worsened the situation, leading to more unrest. Further aggravating both situations was the fact that replacing an old system with a completely different one (whether in politics, business, or sports) typically sees things deteriorate further before they improve. Unfortunately, the high expectations for rapid improvement did not give the new regimes the time they needed to turn things around.

The crisis stage of revolution

Faced with growing unrest at home and military defeats abroad (the French having rashly declared war on Austria and Prussia in 1792), the moderate governments in France and Russia saw the rise of more radical factions supported by the urban working classes, which alarmed foreign powers and spurred them to intervene before the respective revolutions got out of control. Such intervention (by the First Coalition in France’s case and Russia’ erstwhile allies in World War I) in the short run just destabilized France and Russia further, which led to more military defeats, more support for the radicals, and so on.

In each case, this was the crisis stage of the revolution, where extreme radicals seized power and imposed harsh dictatorial rule to deal with the current emergency. In France it was the Jacobins, supported by the Sans Culottes, who imposed emergency economic measures, a universal draft, and the reign of terror. Similarly, Russia saw the Bolsheviks, supported by the working class soviets who imposed war communism to deal with the economic crisis and the Red Terror, which they consciously copied from the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror.

Conservative retrenchment and the dictator stage

In both revolutions, final victory and exhaustion from the crisis stage led to a brief conservative retrenchment to help their respective peoples recover. In France this was the period of the somewhat loose and corrupt Directory (1785-99). In Russia, this was Lenin’s New Economic Policy that allowed a degree of free enterprise to return so the economy could recover.

However, the overthrow of the Directory by Napoleon Bonaparte and Stalin’s rise to power after Lenin’s death in 1924 led to ruthless dictators who masked their repressive regimes with the revolutionary ideals they supposedly represented. Although Napoleon was finally defeated and Stalin won World War II and kept power till his death in 1953, both dictators effectively ruined their respective countries with their harsh policies.

Gradual evolution toward stable economy & democracy

Therefore, Russia has taken longer in its evolution toward democracy than France did, because it took another thirty-five years for Russia to finally collapse beneath the weight of the Stalinist system. Despite, this, Russia has continued to follow a path similar to France’s. After Napoleon France would undergo two more revolutions (in 1830 and 1848) and abortive attempts at democracy that would lead to a second dictatorship, this time under Bonaparte’s nephew, Napoleon III. Unlike his uncle, Napoleon III was much less aggressive in his foreign policy, focusing on France’s economic and industrial development. As a result, when Napoleon III fell from power in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War, he left behind a strong economy and politically active and savvy middle class that ensured the stability of France’s Third Republic.

Likewise, Russia would see the overthrow of communism in 1991 and the establishment of a republic. However, as with France in 1830 and 1848, Russia’s economy was a shambles and it had virtually no middle class with which to sustain a viable democracy. Since then, Vladimir Putin has taken charge and, much like Napoleon III, has ruled with a firm hand while promoting economic growth. Presumably the middle class emerging from that growth will establish a stable democracy sometime in the future.

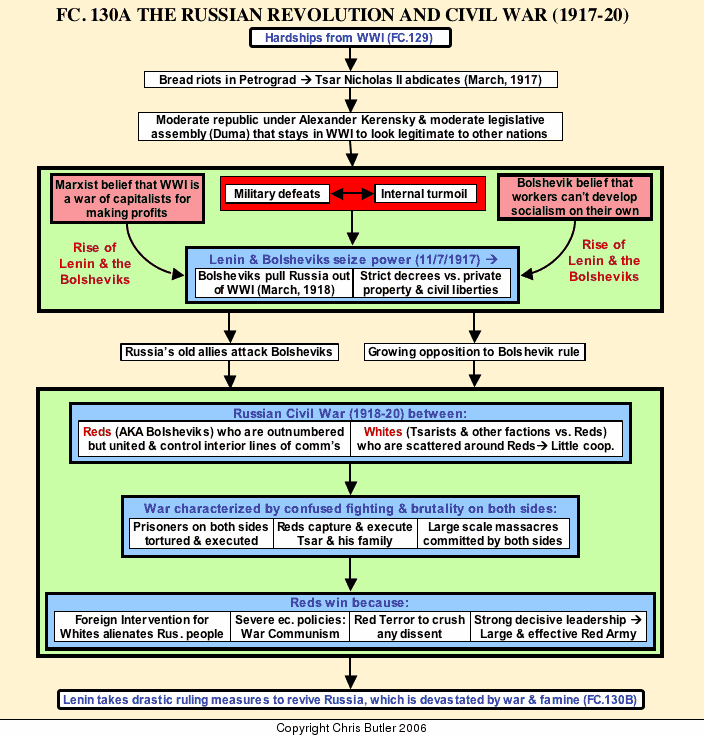

FC130AThe Russian Revolution and Civil War (1917-20)

We are not carrying out war vs. individuals. We are exterminating the Bourgeoisie as a class. We are not looking for evidence or witnesses to reveal deeds or words vs. the Soviet power. The first question we ask is to what class does he belong, what are his origins, upbringing, education or profession? These questions define the fate of the accused. This is the essence of the Red Terror.— M. Y. Latsis

The 1917 Revolution and Bolshevik triumph.

Not only was Russia bleeding from war, it was also starving. This situation sparked bread riots in Petrograd (renamed that from the German St. Petersburg) in March 1917. Day after day the riots escalated as the government failed to respond decisively to the crisis. Many soldiers joined the demonstrators, Nicholas abdicated his throne, and the Duma set up a moderate republic under Alexander Kerensky.

The Russian Revolution followed a course very similar to that followed by the French Revolution. For one thing, its first government, like France’s National Assembly, was a moderate government that tried to maintain respectability by following many of the old monarchy’s policies. The most ruinous of these policies was its commitment to stay in the war against Germany. This merely intensified the turmoil and anarchy that the war had already generated, which led to more defeats, and so on. The more radical elements agitated for more sweeping changes to undermine the government’s power while exploiting its tolerance and weakness.

The most important of these groups was the radical Marxist party known as the Bolsheviks. (meaning “majority” although they only represented a minority of Russian socialists, let alone the population). Their leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, was a hardened revolutionary and prolific writer, whose career had involved avoiding the Czar’s secret police, spending time in a prison camp, and publicizing Marxism through his writing while in exile. Ironically, when revolution broke out, the Germans sneaked him into Russia, hoping he would destabilize Russia and knock it out of the war. He did that and much more.

When Lenin arrived in Petrograd, he immediately set to work to organize a revolution that would overthrow Kerensky. The steady deterioration of Russia from the prolonged war effort played into his hands, and the Bolshevik program, summarized in the slogans “Bread, peace, and freedom” and “All power to the Soviets” won many followers, especially among the soviets (workers’ councils organized in the factories). Finally, on November 7, 1917, the Bolsheviks made their move. Having already seized key strongpoints such as bridges, railroad stations, and telegraph offices, they easily overthrew Kerensky’s government.

Lenin acted quickly in both domestic and foreign policies. In foreign affairs, as he had promised, Lenin pulled Russia out of World War I by signing away large territories in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March, 1918. Russia’s allies were furious since this freed one million German solders for the Western Front. They also feared and hated the Bolsheviks for their claim that they would overthrow Capitalist society. Therefore, the allies, especially Britain and the United States, landed troops in Russia to try to overthrow the Bolshevik government.

Facing strong opposition at home and abroad, much like the Jacobins had in 1793, Lenin followed strict domestic policies. Private property was abolished, industries and banks were nationalized, and the press, briefly free under Kerensky, was once again strictly censored. This combination of internal resistance and foreign intervention led to civil war.

The Russian Civil War (1918-20).

At first the Bolsheviks (also known as the Reds), like the Jacobins in the French Revolution, were heavily outnumbered by their enemies (the Whites) and controlled only about 10% of Russia. That was mainly around Moscow, which they had switched to their capital since it was inland and harder for invaders to reach. The fighting was very confused and brutal, with massacres on both sides. However, the Bolshevik leader, Leon Trotsky, starting with a few units of militia known as the Red Guard (similar to the National Guard in the French Revolution) built the Red Army into a strong and effective force of 5,000,000 men.

Desperate for experienced leaders, he forced old royalist officers into service. To ensure their efficiency and loyalty Trotsky held their families hostage and used a system of political advisors, Commisars, similar to the French Revolution’s representatives on mission. Trotsky’s methods were successful, and by 1921, he had cleared Russia of the foreign invaders and crushed the Whites.

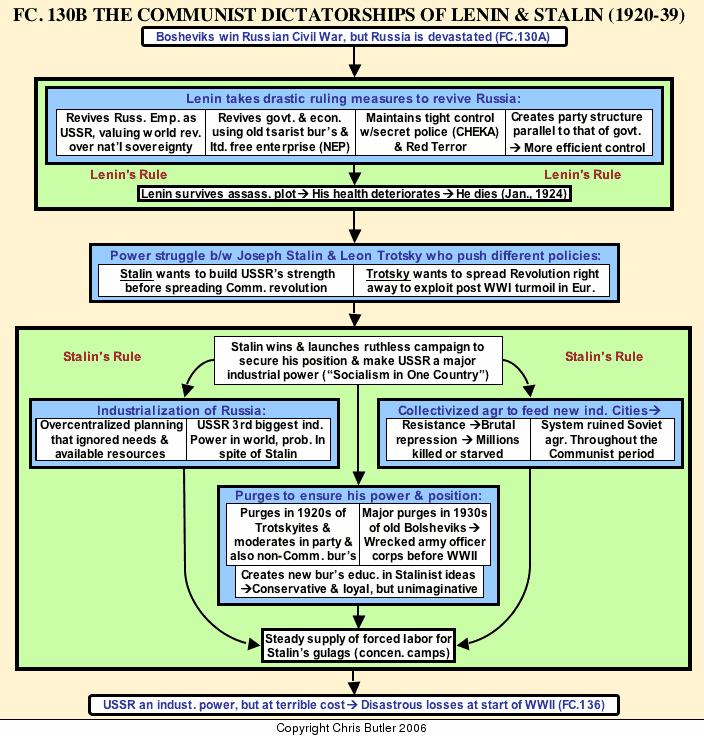

FC130BThe Communist Dictatorships of Lenin & Stalin (1920-39)

Lenin’s Rule

After the devastation of World War I, the Revolution, and Civil War, Russia was a total wreck. Factories were in ruins and half the working class gone, either dead or returned to the farms. Millions had died, mainly from the famine and disease accompanying war. Two million more, mostly nobles, middle class, and intellectuals, had emigrated to other countries. Now it was up to Lenin to restore some degree of prosperity and order. There were four main policies he followed, one that loosened his control for the time being and three that tightened his control.

Lenin eased up a bit with his New Economic Policy (NEP), which allowed some degree of free enterprise to encourage higher production by the peasants. While Lenin had little choice but to let free enterprise return, he could also justify NEP in Marxist terms since, according to Marx, Russia would have to evolve through a capitalist phase before it was ready for Socialism. For several years in the 1920’s, Lenin’s Russia saw widespread experimentation in the arts and social engineering as well as economics. Cubist and futuristic art flourished. Avant-garde theater featured acrobats as well as heavy political messages. The family was also under attack as a bourgeois institution with women as the oppressed working class. Therefore, women gained equal rights and pay as well as access to easier divorces and legalized abortions. Some young communists even saw free love and public nudity as revolutionary acts of liberation from bourgeois values. Older Bolsheviks frowned on such acts, but tolerated them in the spirit of creating a new socialist society. Lenin made similar concessions in government, giving tsarist bureaucrats and technical experts more authority in running the government and factories since most communists were uneducated and untrained in the technical expertise needed to run a country.

However, this is not to say that Lenin relinquished any political control over Russia. For one thing, the old non-Russian provinces of the tsarist empire were brought back under tighter control, the rationale being they needed Russia’s help in establishing a socialist paradise more than they needed national independence, which would be irrelevant once the workers’ revolutions had swept the globe. Of course, to these subject peoples, this new Soviet Union looked suspiciously like the empire of tsarist Russia.

Lenin exerted greater control over local governments through the Communist Party. One problem he had from the earlier days was that the local soviets had seized control of local governments. Although the Bolsheviks themselves had used the slogan, “All power to the Soviets” and could do little to control the soviets during the crisis of the civil war, Lenin was determined to eventually get tighter control on local matters. What he did was create a party structure parallel to that of the government. The local party officials were much more tightly controlled than the soviets and correspondingly more efficient in carrying out Lenin’s directives. As a result, control of the Communist party was as important for the rulers of the Soviet Union as was control of the government as a means for ruling the country.

Finally, Lenin, like Marx, felt the workers could not achieve true revolutionary consciousness on their own, but needed a strong centrally directed party of Marxists to lead them to socialism. Therefore, he had to resort to what he called “Proletarian dictatorship” to ensure the workers got what they deserved. However, this was not rule by the working class, but rather rule by the Communist party with working class members in it. Of course, Lenin strictly ruled the party, thus theoretically making his will that of the party and the people. Enforcing “proletarian dictatorship” and the “Red Terror” was the CHEKA (the All Russia Extraordinary Commission for Combating, Counterrevolution and Sabotage). This was Lenin’s secret police, except that it was much larger, more effective, and deadly than the Czar’s secret police had ever been.

The harsh and autocratic nature of the Soviet system that emerged was influenced by several factors. First, there was the dictatorial nature of Lenin’s personality that largely determined the course of the revolution. Second, there was a certain continuity from the tsars’ absolutist regime to Communist rule. Finally, many more Communists had joined the party during the revolution and civil war than before 1917. As a result, they saw the revolution in military terms as a sort of brotherhood in arms, and it assumed a military aspect with party members wearing military uniforms and using military jargon for political offices and concepts.

However, before Lenin could enact a thorough program of reform in the Soviet Union, he died in 1924. He was a brilliant leader and sincere revolutionary who oftentimes ignored human feelings in pursuit of his Communist revolution. His harsh measures must be seen in light of the harsh conditions that demanded them if the Revolution were to survive. Lenin is remembered as the father of the Revolution, but his early death left to his successor, Stalin, the job of carrying out the real revolutionary transformation of Russia.

Stalin’s revolution (1924-40).

Lenin’s death led to a power struggle between Leon Trotsky, the creator of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, and Joseph Stalin. Stalin was one of the few real working class members of the Communist party’s upper ranks. The name Stalin, meaning “man of steel”, reflected his willingness to take on jobs no one else wanted, gathering a lot of power into his hands in the process. He was also a cold and ruthless politician who managed to squeeze out the more intellectual Trotsky. Not content with a mere political victory, Stalin’s agents later tracked down Trotsky in Mexico and murdered him in 1940.

While Trotsky had wanted to focus on spreading the Communist revolution worldwide, Stalin wanted to concentrate on building up the Soviet Union internally first. He felt a need for a revival of the revolutionary spirit since many Communists thought Lenin’s NEP had steered Russia away from a true socialist society. His first step was to purge the moderate wing of the party that still wanted to continue Lenin’s policies. Among his victims were the middle class and non-Communist bureaucrats and technicians that Lenin had relied upon to keep the state and economy working. While this was popular with the more radical Communists, it also deprived Stalin of the very people he needed to develop Russia’s industries. Stalin then launched a campaign to build the Soviet Union into a great power. His program had three parts: the transformation of the Soviet Union into an industrial power, collectivization of the farms in order to support the populations in the new industrial cities, and a purge of any elements Stalin suspected of disloyalty.

Stalin’s industrialization was carried out in a series of Five Year Plans where the government set projected goals for economic growth. However, the first Five Year Plan (1928-32) in particular was as much political rhetoric as economic planning, which seriously hampered efforts to meet its goals. For one thing, human and material resources were not adequately figured into the plan, causing constant confusion and work stoppages. However, at least officially, each of Stalin’s Five Year Plans more than met their goals. How much of this was the truth, Stalin lying to the world, or nervous officials lying to Stalin is hard to say. There were harsh penalties, even executions, for officials failing to meet their quotas, thus providing strong incentives to meet their quotas by padding their figures or even sabotaging each other’s efforts.

Whole new cities and even lakes appeared where none had existed before, many of them named after Stalin himself. Oil production trebled, while coal and steel production rose by a factor of four times. Stalin also established a massive system of public schools and universities to provide a literate (and more easily brainwashed) work force as well as engineers for his factories. By 1940, the Soviet Union had an 85% literacy rate and was the third largest industrial power in the world behind only the United States and Germany.

However, this was done at a price. For one thing, Stalin concentrated on heavy industries, such as steel, electricity, and heavy machinery, and consequently ignored the production of basic consumer goods, including even housing, for his people. He also used virtual slave labor by taking millions of peasants and others whom he saw as threats to his regime and using them in building his massive canal, hydroelectric dam, and factory projects. Thus millions died for Stalin’s dream of an industrial state.

Collectivization of the agriculture was mainly a means to an end: to produce enough food to support an urbanized industrial society. Marxist doctrine forbade private property, and Stalin, wanting as much centralized power as possible, used this principle to gather the farms into giant state-run operations. In theory, organizing the farms along the lines of industrial factories should increase productivity enough to support the Soviet Union’s new industrial cities. However, there were several flaws with this. First of all, such a scheme demanded a level of mechanization far beyond the Soviet Union’s capacity, which, at that time, still had 5.5 million wooden plows in use. Also, Stalin failed or refused to recognize that people work harder if they feel they are working for themselves instead of a landlord, even if that landlord is the state. Since many peasants had gained possession of their own land before and during the Revolution, collectivization met with strong resistance from these landholders, known as kulaks, and that led to untold troubles.

Stalin saw the kulaks as traitors to the Revolution and launched an all out campaign against them. Police and soldiers surrounded villages and hauled the peasants off to collectives, labor camps (which provided slave labor for Stalin’s industrial projects), or mass executions. Collectivization was also a disaster for Soviet agriculture and its people. Peasants burned their own grain and butchered their livestock to keep them out of government hands. That and the disruption caused by Stalin’s harsh policies led to widespread famine that killed millions more. Any gains Soviet agriculture may have made were probably in spite of Stalin, not because of him. This brings us to the third feature of his regime, the Stalinist terror.

Stalin was an extremely paranoid man who easily imagined both that anyone not meeting his expectations of performance was a traitor to the state and that anyone exceeding his expectations was an ambitious conspirator against him. In 1936 Stalin purged a wide range of people whom he saw as traitors or threats to his regime: government officials, military officers, old Bolsheviks, and teachers in addition to kulaks and inefficient factory managers.

The trials of these people were an absolute farce, where the accused were forced to read contrived confessions of their alleged crimes against the state before being sent to Stalin’s labor camps, providing much of the slave labor needed for Stalin’s industrial projects. However, the purges did great harm to Russia. Besides stifling initiative and poisoning society with an element of fear, they also eliminated most of the Red Army’s top officers, replacing them with men who were inexperienced and subservient to Stalin. Russia would pay a terrible price for this in World War II.

Those replacing the bureaucrats and engineers eliminated by Stalin’s purges were young men from working class backgrounds educated in the new schools and universities established by Stalin. Instead of the radical and somewhat independent-minded Bolsheviks in military uniforms agitating for more revolutionary reforms, Stalin now had an elite corps of educated engineers and bureaucrats loyal to him and more concerned with technical matters and industrialization than factional politics, Marxist ideology, and loyalty to a fighting Marxist brotherhood. Instead of uniforms and eccentric cultural ideas, they wore suits and attended classical concerts and ballets. They were the products of the revolution, but they were hardly revolutionary themselves, being prone to conserving the gains made by their party rather than pushing toward new frontiers. Stalin’s two successors, Khruschev and Brezhnev, both came from this generation and reflected its more conservative tendencies. The revolution had come full circle.