The Post-War World (1945-60)Unit 21: The Post-War World (1945-60)

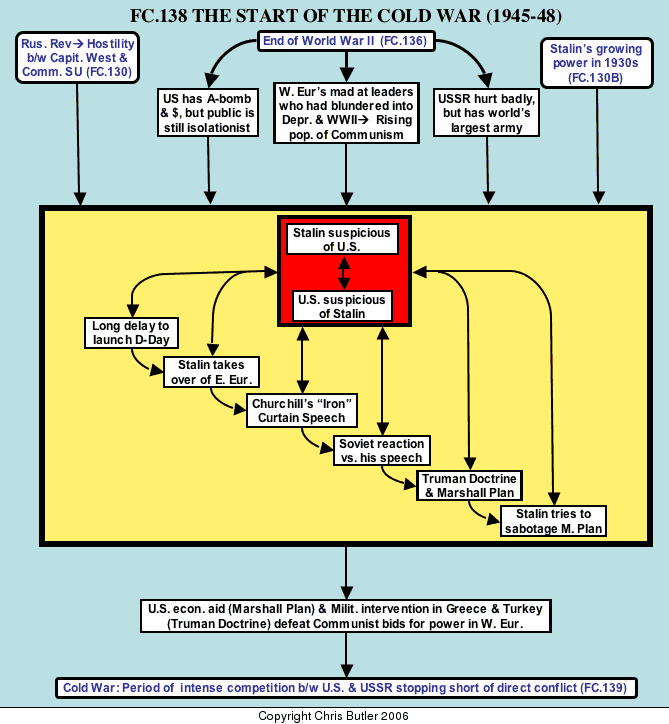

FC138A New Balance of Power and Cold War (1945-1948)

The aftermath of World War II

The human capacity for self-destruction had reached new heights in World War II. An estimated 55,000,000 people had died, 27,000,000 in the Soviet Union alone. Most of the dead were civilians who just happened to be caught in the path of a new and ever more destructive warfare. In addition to the dead were another 50,000,000 refugees. There were people displaced by the war trying to find their ways home, Jews still being persecuted even in the aftermath of the war, Germans driven from their homes as Stalin cut back Germany's borders to make room for his own expansion, and Soviets released from German prison camps only to be forced to return home as "traitors" to face Stalin's labor camps. Refugees flocked to the cities desperately seeking jobs, food, and shelter, only to find mountains of rubble. Hardly a city in Europe had escaped the roar of the bombs, with some cities, such as Stalingrad and Berlin, being 95% destroyed. No wonder that one post-war observer referred to Europe as "half graveyard and half junkyard."

A new balance of power emerges (1945-48)

When the allied armies met in triumph at the Elbe River in May 1945, all seemed to be smiles and comradeship. But with the common Nazi enemy gone, old animosities quickly resurfaced, causing the Western allies and Soviet Union to establish spheres of influence from which they would eye each other suspiciously during the next half-century. For the first years after World War II, there were three main issues: Soviet intervention in Eastern Europe, the political struggle for Western Europe, and the role the United States would play in the world.

Even by 1947, two years after the war, Western Europe had seen little apparent progress in recovering from the war. Roads and bridges were still in disrepair; cities were still largely piles of rubble, and consumer production was only half of what it had been in 1939. Britain and France, the two main European powers who in the past might have led the way in reconstruction, were themselves severely weakened by the war's staggering cost and growing unrest in their colonies. All this produced a good deal of dissatisfaction with the conservative governments that had failed to avert the Depression and World War II and seemed to be doing little to restore things to normal. Benefiting from these problems were the Communists, who had led much of the partisan resistance to the Nazis and now were gaining popularity and votes.

Although Russia was severely damaged by the war, it also had the world's biggest army, and Stalin was determined to use it to guard his country against a repeat of the last four years. In the post-war years, Stalin rebuilt much of Soviet industry while ignoring the needs of his people. For example, by 1948, Stalingrad, which had lost 95% of its industries and population, had restored 60% of its population and 70% of its factories, but had rebuilt only 20% of its housing. Stalin's domestic policy was driven by his intense suspicions of the West. There were several reasons for this: the long time it took for the Allies to open the second front in Normandy, American possession and use of the atomic bomb at the end of the war, and the deep ideological differences between communism and capitalism. For these reasons, he decided to establish a buffer zone in Eastern Europe to forestall any future aggression.

Stalin's domination of Eastern Europe generally followed a fairly insidious but effective pattern. First the Red Army would liberate the country from the Germans. Then the Communists would form a coalition government with other parties while holding key government posts, in particular the ministry of the interior that controlled the police. Using propaganda, gangs of thugs much like the Fascists had used, and the threat of military force from the police and (if necessary) the Red Army, the Communists would gradually force their opponents from the government until only they remained.

As a result, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania, fell under Soviet domination with Soviet troops occupying their territories. Only Yugoslavia, by quickly going Communist and making an outward show of obedience to Stalin, escaped Soviet occupation and kept some measure of independence. For the rest of Eastern Europe, in Churchill's words, an "iron curtain" had descended to keep it firmly under Stalin's heel.

In sharp contrast to this was the United States, whose territory had been virtually untouched by the war. Partly by default due to the war's damage elsewhere and partly by right of its vast resources and industrial strength, the United States in 1945 was by far the number one economic power in the world, controlling an estimated 60% of the world's industrial production.

While the United States was the only nation capable of stopping the Communists, the protection of two oceans made America isolationist at heart. However, having been dragged into two world wars in quick succession, many Americans reluctantly recognized that they were an integral part of a larger world. The fact that a new, hopefully more effective international body, the United Nations, was headquartered in the United States symbolized America's new role in world affairs. Americans also felt increasingly betrayed by the actions of their former ally, Stalin: his stall tactics at the Potsdam Peace Conference (July, 1945), his support of Chinese Communists in their civil war, and his takeover of Eastern Europe. Thus a growing sense of global responsibility and fear of the spread of Communism led the United States to get actively involved in Western Europe.

All these factors, the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, the situation in Western Europe, and the United States' gradual acceptance of its role in the world at large, combined to create a two pronged policy. Militarily, President Truman committed the United States to stop Communist aggression in Greece and Turkey in what was known as the Truman Doctrine. In the 1950's, the Eisenhower Doctrine issued by President Eisenhower would expand this policy, known as containment, to stop Communist aggression wherever it occurred. At this point, however, the main focus of the Truman Doctrine was Greece. A bitter civil war between Communist guerrillas operating from mountain bases and government forces in the valleys had been raging since the end of World War II. American military aid and advisors managed to help the government forces stop the Communists and drive them out of Greece by 1949. However, Greece had suffered horribly in this civil war following right on the heels of World War II.

America's economic response was known as the Marshall Plan (1948). Its basic premise was that Communism thrived in economically backward or disrupted areas. Therefore, large amounts of foreign aid to revive Europe's economies would deprive the Communists of the conditions on which they thrived, save Western Europe from Communism, and provide the United States with stable trade partners and markets. Marshall Plan aid was offered to any country desiring it, including the Soviet Union. Stalin, not wanting to be dependant on the West, refused the aid, as did his satellites in Eastern Europe.

However, Marshall Plan aid made a huge difference in Western Europe, especially France and Italy which were in danger of Communist takeover. When American aid was announced, French and Italian Communists made a final bid for power by disrupting their nations through strikes, riots, and even sabotage of public works such as railroads. In each case, the Communists largely discredited themselves, while the more moderate democrats had the Marshall Plan aid to back them up and win over voters. As a result, Western Europe experienced a remarkable economic recovery after this.

The Cold War begins (1948-55)

By 1948, the United States and Soviet Union had established their spheres of influence in Western and Eastern Europe respectively. Unlike World War I when a definitive treaty emerged to determine a new balance of power, no such treaty emerged after World War II. This was because there was such a quick falling out between Stalin and the Western allies after the war. The fates of Western Europe and Eastern Europe had been determined without direct confrontation between the two superpowers. But, by 1948, when the two superpowers had established their spheres of influence, they started confronting each other in what is known as the Cold War.

The Cold War was a period of hostility and competition between the United States and the Soviet Union that always stopped short of direct war between them. It never erupted into open warfare, mainly because their growing arsenals of nuclear weapons made such a war seem suicidal to both sides. Therefore, the Cold War assumed the form of a series of crises that were resolved along two lines of development: either by non military means or by fighting by proxy (substitute) where one or both powers fought each other by supporting smaller allied states in regional wars. The Korean (1950-53), Vietnam (1954-75), Arab-Israeli (1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982), and Afghan (1979-89) wars were all examples of the superpowers exploiting regional conflicts to promote their own ends.

Crises resolved through non-military means actually ran a higher risk of erupting into all out war, since the Americans and Soviets were directly opposed to one another. In these cases, each side would play a dangerous game of brinkmanship where it would try to push the other side into a position that would make any further escalation of the crisis run the risk of full-scale war. The initial stages of the Cold War were played out in two widely separated theaters corresponding to the two main theaters of World War II: Europe and Asia.

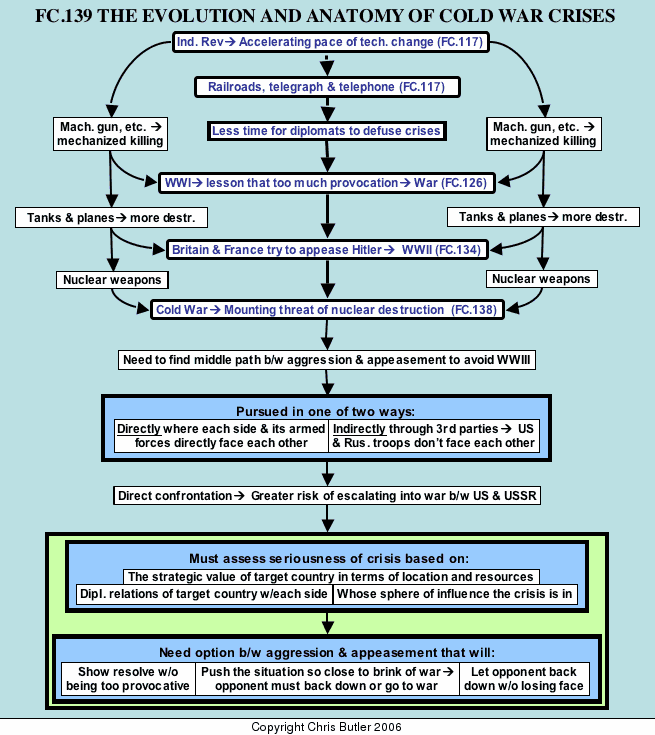

FC139New Rules for A New Game: the Evolution and Anatomy of Cold War Crises

Introduction

By 1948, the United States and Soviet Union had established their respective spheres of influence in Western and Eastern Europe. However, unlike World War I when a definitive treaty emerged to determine a new balance of power, no such treaty emerged after World War II because of the quick falling out between Stalin and the Western allies. So far, the post-war settlement had been determined without direct conflict between the two superpowers. But, by 1948, when the two superpowers had established their spheres of influence, they started confronting each other in what is known as the Cold War.

The Cold War crises always stopped short of direct war between the two sides because their growing nuclear arsenals made such a war potentially suicidal to both sides. Already by 1945 two world wars in quick succession had shown the spiraling destructive potential of modern technology. At first, it took a while for both sides to realize nuclear weapons were much more than just big conventional bombs. Even when that lesson sank in with the realization that nuclear war was played by a different set of rules, it still was not clear just what those rules were; but it was clear we could not risk such a conflict. Before the twentieth century, diplomacy could more freely use war and/or the threat of war as tools in its arsenal. However, with the nature of war so radically different, the rules of diplomacy also had to change drastically. The question was how. To the diplomats and leaders who had gone through two previous world wars, the answer largely lay in analyzing what had gone wrong in 1914 and 1939.

Wars and crises up to 1945

The root of the problem lay in the mismatch between the slow rate of change in cultural attitudes toward war and the accelerating pace of technological change triggered by the industrial revolution. By 1914, industrialization had spawned revolutions in communications, transportation, and warfare. In communications, the telegraph and telephone drastically cut the time of communications between governments. That alone might have been manageable, except that, with the telegraph used in conjunction with railroads, armies could mobilize much more quickly, giving diplomats hardly any time to reflect on their situations and negotiate a settlement. As a result, the various powers’ provocative behavior in 1914, especially Russia’s mobilization (an act once accepted as a legitimate diplomatic strategy) spun out of control into war.

During World War I new weapons such as the machine gun, poison gas, and more powerful artillery unleashed a level of carnage and destruction hitherto undreamt of. Between the wars, diplomats, in their efforts to prevent another such disaster, focused on, and tried to avoid the provocative diplomacy of 1914. Unfortunately, they went too far in their efforts to keep the peace in the 1930s, constantly meeting Hitler’s aggression with appeasement. This only encouraged more aggression while Hitler built up his power. Therefore, the Second World War II broke out only twenty years after the end of the First.

In 1939, the tank and airplane, which had just made their debut in the previous war, came into their own. Tanks, rather than eliminating the continuous front, made it mobile, thus spreading the swathe of destruction from a limited static front to one that engulfed all off Europe. Airplanes exacerbated this effect, especially with long-range strategic bombing that now made cities and their civilian populations primary targets.

Unfortunately, if the Second World War seemed to spawn another quantum leap in the destructive capability of modern technology, the entry of a weapon of even more devastating power heralded the end of that era and the start of a whole new era in the history of human warfare: the atomic bomb. Even more ominous was the development of thermonuclear, or hydrogen, bombs just seven years later using a fusion reaction to generate an explosion that dwarfed that of the of the Hiroshima bomb’s fission reaction in much the same way that it had dwarfed conventional bombs. Whereas a simple chemical reaction was the basis of warfare in the age of gunpowder (c.1500-1945), the key to the Atomic Age was a much more complicated chain reaction taking place inside the nucleus of the atom, something so small we still didn’t have microscopes powerful enough to see it. But we could unleash, if not control, its destructive force. Now the very survival of civilization was on the line, and a way had to be found to avert a clash between the two nuclear superpowers, the United States and Soviet Union.

The new rules of the game

Therefore, the Cold War assumed the form of a series of crises that were resolved along two lines of development: either by non military means or by fighting by proxy (substitute) where one or both powers fought each other indirectly by supporting smaller allied states in regional wars. The Korean (1950-53), Vietnam (1954-75), Arab-Israeli (1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982), and Afghan (1979-89) wars were all examples of the superpowers exploiting regional conflicts to promote their own ends.

Crises involving the Americans and Russians in a direct confrontation ran a higher risk of erupting into all out war. Therefore, each side would carefully assess the seriousness and strategic value of the crisis to its own and the other side to calculate how far it could go without starting World War III. This assessment would be based largely on three factors. First was the strategic value (in terms of location and/or resources) of the target country at the center of the crisis. For example, any crisis over the oil-rich Middle East would have serious implications. So would a crisis over any strategic choke points such as the Suez and Panama Canals or Turkey’s control of the Hellespont threatening Russia’s access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

The second and third factors were which superpower’s sphere of influence the target country occupied and the diplomatic ties it had with each side. These would usually, but not always, belong to the same power, giving that power a decisive “home field” advantage in the crisis. However, crises where diplomatic ties did not correspond to the sphere of influence tended to run the highest risk of escalating into war because it wasn’t clear who held the all-important home field advantage.

Two examples of such a situation were the Berlin Blockade in 1948-9 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. In the former crisis, West Berlin had strong diplomatic ties with the West but was located in the middle of Soviet controlled East Germany. The Cuban Missile Crisis saw just the opposite situation, with Cuba in the United States’ traditional sphere of influence, but having strong diplomatic ties with the Soviets. In each case it was unclear who had more at stake and was willing to go farther in defense of what it believed to be its “home turf”. This was where the chances of miscalculation and the risk of war ran the highest.

Having assessed the risks in a crisis, each side needed to pursue a strategy between being too aggressive and too weak, such as those which led to World Wars I and II respectively. This needed to meet three criteria. First, it must show strength and resolve without being too provocative. Second, playing a dangerous game known as brinksmanship, it should push the other side into a position that would make any further escalation of the crisis run the risk of war, thus forcing it to back down. For example, during the Berlin Blockade, the United States and Britain airlifted supplies into West Berlin rather than crashing the land blockade Stalin had set up. This avoided committing an act of aggression that might lead to war and it forced Stalin into the position of either letting the planes through or actively shooting them down, which would also lead to war.

Finally, the strategy in a crisis should provide the opposition a face-saving way to back down without feeling publicly humiliated. The United Nations could play a valuable role here as mediator to defuse the crisis. So could secret diplomatic deals between the two powers, such as the secret agreement by the U. S. to remove its missiles from Turkey if Russia would publicly agree to take its missiles out of Cuba in return for a public commitment that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. Recognizing the value of such secret “back channels”, the two powers installed a “hot line” after the Cuban Missile Crisis, thus providing direct communications with one another during any future crises.

It is important to note that these were not hard and fast rules that were ever written down in a handbook so both sides knew exactly how to deal with one another. Rather they were vague principles that evolved through trial and error as the two sides struggled to find a way to deal with the new sort of world nuclear weapons had created. However poorly articulated these principle were, during the most dangerous half-century of human history to that point they helped the United States and Soviet Union break the pattern of resolving differences through total war. In the process, they avoided nuclear Armageddon and provided some glimmer of hope that the human species might survive its technological adolescence.

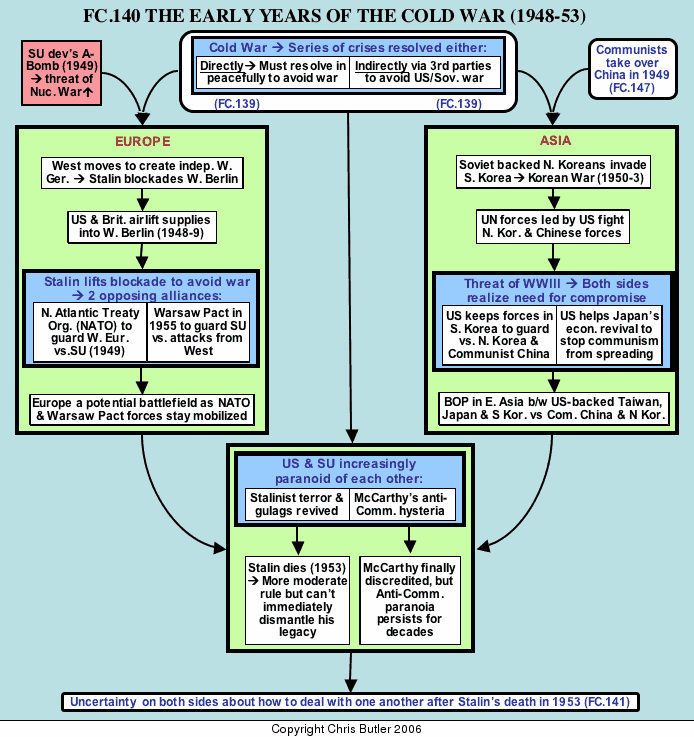

FC140The Early Cold War (1948-53)

The Cold War in Europe (1948-55)

The first Cold War crisis was over Germany, through which the victors had drawn the line of demarcation between Soviet and Western spheres of influence in 1945. France, Britain, and the United States held the Western two-thirds of Germany, while Russia held the eastern third. At first this division was meant to be temporary with a permanent settlement to be hammered out in the future. But Stalin and the Western allies were soon at odds over the fate of Germany. Stalin wanted it to be Communist and the Western allies wanted it to be Capitalist and democratic.

In 1948, the United States and its allies made several moves that led to a crisis: a military and economic alliance that was aimed against a resurgent Germany but which Stalin thought was against him, the Marshall Plan to stop the spread of Communism, the unification of the three western sectors into what would become West Germany, and the introduction of a new currency to stabilize the German economy. Stalin kept this new currency out of his sector and tried to introduce his own currency into the West. The allies responded by keeping his currency out of the West. Stalin, sensing a resurgent West German economy and fearing that this might threaten his dominance in East Germany and Eastern Europe, raised the stakes in what is known as the Berlin Crisis.

Berlin, which itself lay deep inside East Germany, was divided between the allies in much the same way as the rest of Germany. The Western allies had access to West Berlin through three land corridors and three air corridors. Therefore, West Berlin was quite vulnerable to Soviet pressure, and that is where Stalin struck.

On June 24, Stalin started cutting off utilities and the flow of traffic and supplies along the three land corridors leading into West Berlin. This presented the Western Allies with a difficult choice. If they abandoned West Berlin to its fate and let Stalin have his way, it would encourage more aggression that might lead to war just as a similar sort of appeasement had done in 1939. By the same token, crashing the Soviet blockade could lead to war just as similar acts of aggression had done in 1914.

The Allied solution was tedious but ingenious: an airlift of supplies into West Berlin. This would supply West Berlin while using three-dimensional air space that could not be blockaded. It was a classic case of brinkmanship, since stopping the airlift would require shooting down American and British planes, which might provoke a war. Since the United States had the Atomic bomb and he did not (at least until the following year), Stalin did not want to risk a war with the United States. Therefore, he let the planes go, hoping the British and Americans would get tired of this whole costly operation. They did not. For nearly eleven months, they kept up the round-the-clock flights that were only 30 seconds apart, taking in supplies and taking out some 50,000 sick, elderly, and very young people. Besides food and medical supplies, they also took in cars, heavy machinery, and even Clarence the Camel, a defiant symbol to Stalin that the Western Allies could bring anything they wanted into West Berlin.

Each succeeding day of the airlift embarrassed Stalin with proof of the West's technical ability to pull off such a feat. After eleven months, he lifted the blockade. The Berlin airlift had saved West Berlin. It had involved 276,926 flights that brought in 1,592,287 tons of supplies at the cost of 24 air crashes and 79 lives. The importance of the Berlin Crisis was that it stopped further Stalinist aggression in Europe. The same month that the blockade was lifted (May, 1949), West Germany was formed as a parliamentary democracy.

The Berlin crisis prompted two rival alliances led respectively by the United States and Soviet Union. In 1949 the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was formed between the United States, Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Greece (1952), and Turkey (1952). It was mainly a defensive alliance to stop Soviet aggression by hemming it in to the west and south. In 1954, the NATO allies, in need of manpower and firepower to combat the Soviets, allowed West Germany to rearm itself and admitted it to NATO. Outside of the United States, the West German army became the biggest and best-trained army in NATO.

A similar alliance, the South East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was formed in 1954 between the United States, Britain, France, Pakistan, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and the Philippines to contain the Soviets and Communists to the south and east. A third alliance, the Mideast Treaty Organization (1955) completed the ring of hostile powers on Russia's borders to the south. These alliances proved to be less stable and reliable than NATO, but they did ring the Soviet Union with unfriendly alliances, which alarmed its leaders.

In response to this threat, Russia formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955 with its satellite states in Eastern Europe: East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Albania. Making this threat much more potent was the fact that the Soviets now had nuclear weapons of their own. In the following years, Britain, France, China, and India all would join the "nuclear club" and develop their own nuclear arsenals.

Therefore, by the mid 1950's, distinct battle lines had been drawn in Central Europe. Armies which people expected to be demobilized and sent home in 1945 remained in place for nearly a half century, draining their countries' economies, turning Central Europe into an armed camp, and presenting the constant threat of war, which this time would probably be accompanied by a devastating nuclear exchange. Whole generations grew up under the ominous cloud of this atomic umbrella, acutely aware that the next war might well be the last for the human race.

The struggle widens: East Asia (1945-53)

World War II had been a truly global war, especially involving Europe's colonial empires in Asia. By the mid twentieth century, the areas outside of Europe loomed much larger in importance as they shook off Europe's grip and started developing on their own economically and politically. Japan had led the way since the late 1800's, and its early success against the European colonial powers inspired others in Asia to challenge European supremacy as well.

One such country was China, whose civil war between the Communists led by Mao Zedong and the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek had been interrupted by World War II. That civil war resumed right after Japan's defeat. Although the Nationalists started out with more men and resources, the Communists were better led and disciplined and had Soviet help. By 1949, the Communists emerged victorious, and the West found itself confronted by another Communist power that was heavily backed by the Soviet Union. The ensuing clash between Communist East and Capitalist West came in a third country: Korea.

The victorious Americans and Soviets partitioned Korea, which had been occupied by Japan since the early part of the century, after the war at the thirty-eighth parallel. Soviet dominated North Korea became Communist; while American backed South Korea was capitalist and democratic in form. In 1950, North Korean forces invaded South Korea and overran most of it.

This crisis brought to the forefront the fledgling United Nations, founded in 1945 in the recurring hope that such an international organization could help defuse conflicts and safeguard the peace. The members of its main executive body, the Security Council, each had the power to veto any proposed actions. As luck would have it, when the Security Council met to discuss the Korean crisis, the Soviets boycotted its meeting. This allowed the United States to pass a resolution calling for an international force to stop the North Koreans.

The bulk of this force consisted of American troops led by General Douglas Macarthur. With the United Nations forces barely hanging on to a toehold in the south, Macarthur landed an amphibious invasion behind North Korean lines and drove them back north. When the U.N. forces advanced dangerously close to the Chinese border in the North, Chinese forces entered North Korea and drove them back south. What ensued was a long bloody stalemate that ended with a ceasefire at the original border, the thirty-eighth parallel. The Korean War had two major results. For one thing, it contained the spread of Communism, but at the cost of a divided Korea and the loss of millions of lives and untold material damage.

It also affected Japan where the United States was worried about the further spread of Communism and Soviet power into East Asia. Feeling that poor and unstable conditions created the ideal conditions for the spread of, the United States decided to provide Japan with economic aid to help it revive. As a result, Japan's prosperity and stability rapidly recovered, making it a strong ally and trading partner for the United States. However, by the 1980's, Japan' was seriously challenging American dominance of world trade.

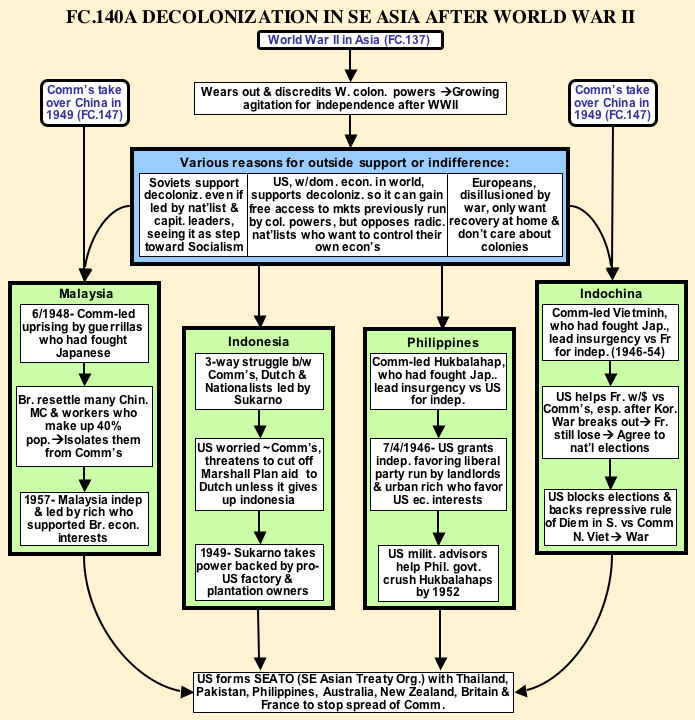

FC140ADecolonization in South-east Asia after World War II

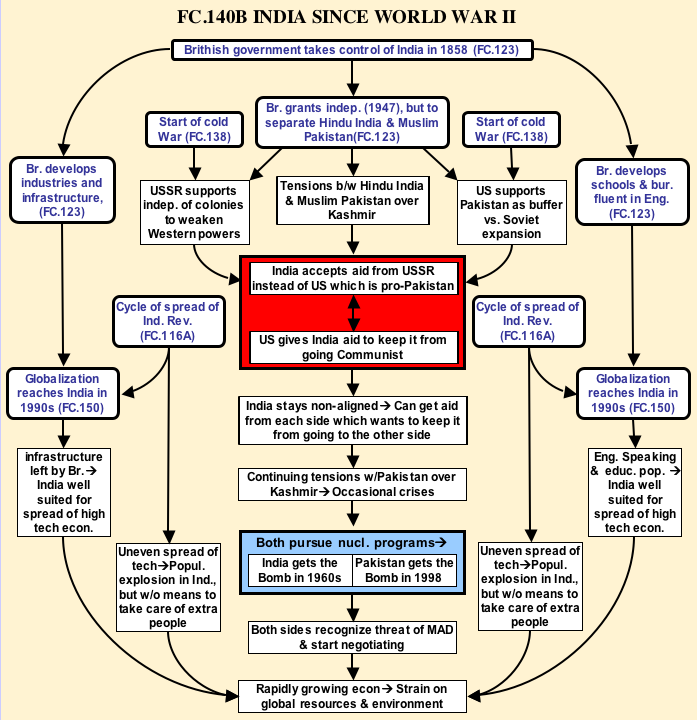

FC140BIndia Since World War II

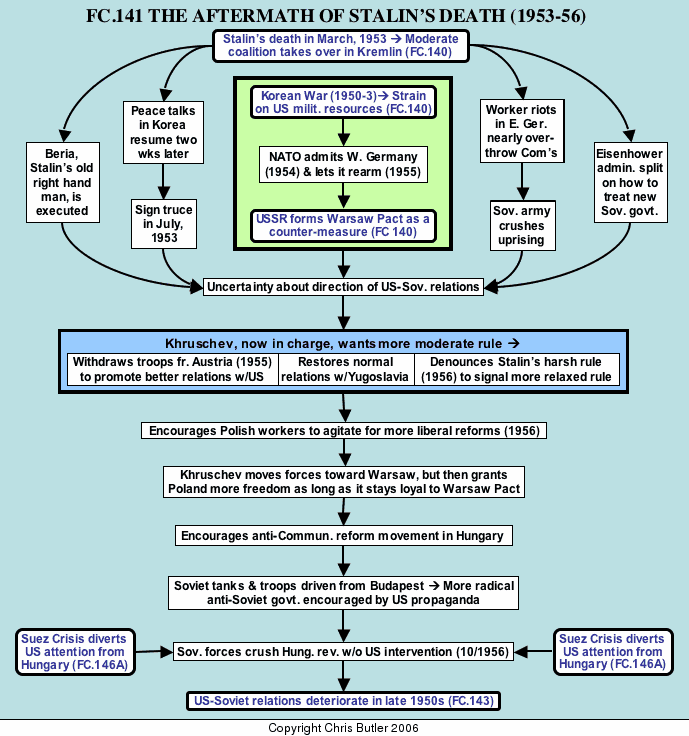

FC141Missed Opportunities: the Aftermath of Stalin's Death (1953-56)

Introduction

The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 marked the end of an era both in the Soviet Union and the world, although no one was sure just what it meant for the future. For many Soviets, the end of Stalin’s brutal dictatorship also meant the end of stability. They wondered who would watch over and defend the Soviet Union now that his strong hand had been removed. To others, it meant an opportunity to dismantle at least some, if not all, the repressive aspects of Stalinist rule. People in Eastern Europe watched anxiously for signs they could gain more liberties, if not outright freedom, from Soviet rule. For the West, it was also an anxious time. Would the new regime in Moscow continue Stalin’s hostility to the West or would it open a new regime of peace and cooperation? Unfortunately, when the dust finally settled by the end of 1956, little would seem to have changed within the Soviet empire or in its relations with the West. Not that people, especially Nikita Khrushchev, wouldn’t try to change things. However, the Stalinist legacy of three decades of repression and paranoia would prove to be too strong to be dismantled within such a short time. To a large extent, it was a period of missed opportunities, but against heavy odds of those opportunities blossoming into a new era of peace and stability.

Mixed signals

Since Stalin had not designated a successor, no single figure emerged in the immediate aftermath of his death. Instead a moderate coalition, led by Georgi Malenkov, took over in the Kremlin that did not even institute a major purge of its enemies. Other hopeful signs followed. Peace talks in Korea resumed only two weeks after Stalin’s death and produced a ceasefire by July. Leaders in the Kremlin were even considering the idea of a reunified, but neutral Germany. Along these lines, they summoned to Moscow the East German leader, Ulbricht, a dictator cut in the Stalinist mode, to encourage him to relax his harsh rule. However, this ultimately triggered a more ominous chain reaction of events.

In June 1953, East German workers, sensing more relaxed control from Moscow, demonstrated against Ulbricht, whose response to the message from the Kremlin had been to impose even harsher work quotas on his people. When the East German government did nothing to respond to these demonstrations, the protests turned political, threatening to overthrow Ulbricht and communist rule in East Germany. Eventually, Beria, the former head of Stalin’s secret police, ordered in Soviet forces and crushed the protests.

However, the Kremlin’s initial indecision during this crisis encouraged similar riots and strikes in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and even Siberia. Many Soviet leaders saw these as attempts by the United States to upset communist rule in Eastern Europe. This generated a backlash against the government’s recent moderate policies as well as a fiercer power struggle within the Kremlin. Beria, saw this as his opportunity to seize power, but was defeated and executed. This was the only notable execution to take place in the aftermath of Stalin’s death. The fact that its victim, Beria, represented more than anyone the old Stalinist legacy was a sign that times had indeed changed.

Unfortunately, two things would prevent the United States from picking up on these cues. One was the recent Red Scare of the McCarthy era that still heavily affected American politics. The administration of the new president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had courted McCarthy’s support during the 1952 election campaign, was split over how to treat these new developments. Even more worrying to the Soviets was West Germany’s admission into NATO in 1954 and the decision to let it rearm the next year. This was done largely due to the strain the Korean War had put on American Military resources. Seeing West Germany as a reliable democracy and ally now, the U.S. decided to use its resources to bolster the Western alliance. However, a rearmed and hostile German state was the last thing Russians wanted to see so soon after World War II. Therefore, they responded by forming their own military alliance, the Warsaw Pact in 1955. Thus the future direction of U.S.-Soviet relations seemed cloudier than ever.

Nikita Khrushchev

By 1955, a new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, had emerged from the power struggle inside the Kremlin. Khrushchev himself seemed to epitomize the mixed signals being sent to the West in the 1950s. He came from a poor working class background and had joined the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. As political commissar at Stalingrad, he had seen firsthand the destruction World War II had wreaked upon the Russian people and understood as well as anyone the even greater destructive power of nuclear weapons. He firmly believed communism was the best way to create better lives for the people. Unlike Stalin and Malenkov, he had a very personable style, going out to meet the people and generating genuine popular support. He prompted more consumer industries, freedom of the arts, better pensions, and freed thousands of political prisoners from Stalin’s gulags. Trying to project “Socialism with a human face,” he even opened the Kremlin to visitors and children’s parties.

However, Khrushchev had also been a loyal follower of Stalin, being instrumental in carrying out many of his harsh policies. Therefore, to many people, especially in the West, he only represented a continuation of Stalin’s harsh rule. In addition, Khrushchev had a somewhat volatile and unpredictable personality, seeming to be waving the olive branch of peace one minute and his saber the next. This made it difficult for the West to know which Khrushchev it was dealing with at any given time. Contributing to Khrushchev’s unpredictability was the conflict between his own genuine desire to improve the lives of the Soviet people and the need to look tough in his dealings with the West in order to satisfy the hard-liners within the Kremlin. In the end, his attempts to follow both of these seemingly irreconcilable policies would lead to his overthrow from power in 1964.

Initially Khrushchev did two things to show a more moderate and reasonable regime was in charge. In 1955, he withdrew Soviet troops from Austria (which had been occupied like Germany since 1945) on the stipulation that it maintain a neutral position between East and West. The next year, in a six-hour speech to a closed session of a Congress of the Communist party, he took an even bolder step by exposing Stalin’s purges as frauds and denouncing Stalin himself as a pathological criminal. When news of this speech leaked out, the common people welcomed it as a sign of more relaxed times to come. However, many communist leaders in the Kremlin and Eastern Europe worried about where this would lead. Those worries soon proved to be justified.

Unrest and crisis in Eastern Europe

Khrushchev’s speech excited new hopes in the West, which continuously broadcast the text of his speech over Radio Free Europe, its main medium of propaganda to Soviet satellite countries. Naturally, this stirred up hopes of freedom from Soviet rule across Eastern Europe. Poland was the first country to react, as its workers’ demands for economic reforms grew into demands for political reforms. At first, Khrushchev moved Soviet forces toward Warsaw, threatening to crush the movement. Then, he seemed to do an about face (especially when compared to how Stalin would have acted) and agreed to give the Poles more freedom as long as they stayed loyal to the Warsaw Pact. This was hardly the end of it, though.

Later that month (October, 1956), student demonstrations erupted across Hungary in support of the Poles. When the Hungarian secret police shot several demonstrators, workers joined the students. Soviet troops sealed off Budapest and fierce fighting ensued. A popular leader, Imre Nagy, was restored to power. His government called for amnesty for the demonstrators along with more liberal political and economic reforms while still assuring the Soviet Union of Hungary’s loyalty. Khrushchev withdrew his troops (many of whom were fraternizing with the Hungarians) from Budapest, but moved more forces close to Hungary’s borders. This only caused demonstrations to spread to the countryside while more and more Hungarian troops joined the demonstrators, taking their weapons with them. Then on November 1st, Nagy repudiated the Warsaw Pact and declared Hungary’s neutrality. Meanwhile, Radio Free Europe kept hopes and tensions at fever pitch by promising support to the rebels.

However, as luck would have it, another crisis, this time over the Suez Canal, had erupted with fighting between Israel and Egypt. With the United States thus distracted, the Kremlin seized the opportunity to move fifteen divisions, including 4000 tanks (which are hard to fraternize with) against Budapest. Even without help from the United States, which probably would not have risked war with Russia over Hungary anyway, the rebels held on for three weeks, even fighting Soviet tanks with homemade bombs called Molotov cocktails, Some 700 Soviet soldiers and 3-4000 Hungarians died in the fighting before Budapest was brought back under control. Nagy was ousted from power and executed along with 300 other rebel leaders. Another 35,000 Hungarians were arrested, while 200,000 more fled to the West.

The Hungarian uprising of 1956 showed how far Khrushchev and the Kremlin would let reforms progress within the Soviet Empire before cracking down. Unfortunately, the West took this as a sign that nothing had changed since Stalin’s death and maintained a hostile posture against Khrushchev, and he responded accordingly. Therefore, an opportunity to ease tensions between the superpowers backfired, causing the Cold War to heat up even more in the years to come.

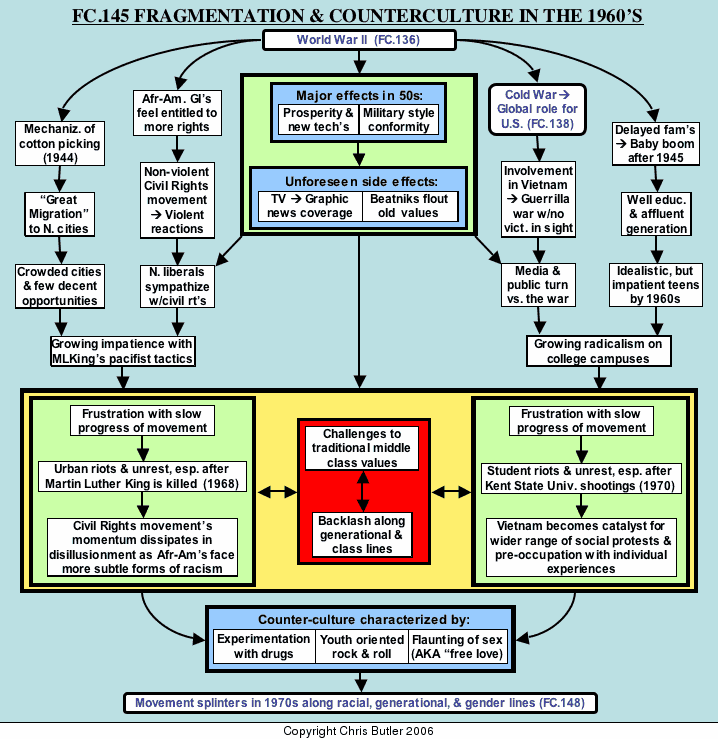

FC142Postwar Conformity and the Seeds of Dissent in the 1950s

Pressures to conform

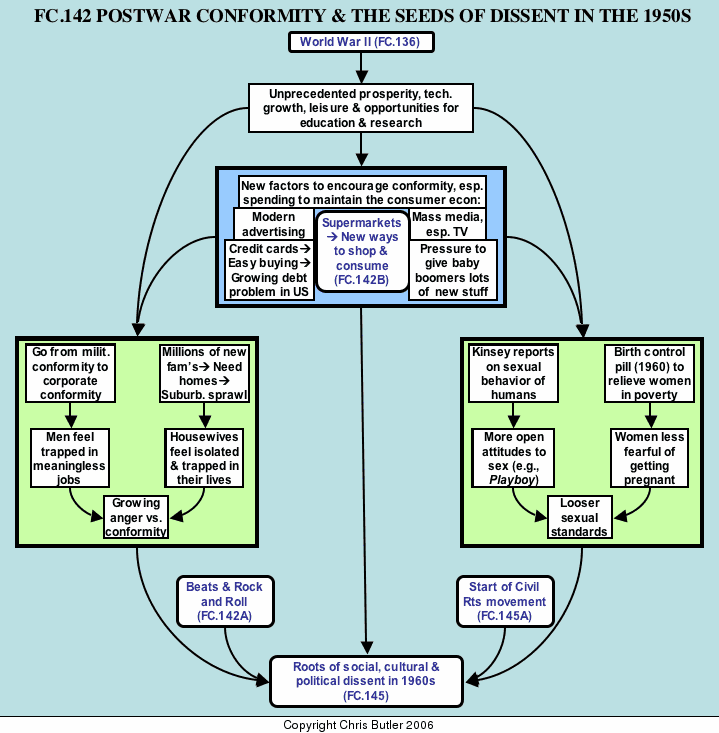

World War II gave Americans an unprecedented era of affluence, technological growth, leisure, and opportunities for education and research. Out of this came four new factors pressuring people to conform, and especially to spend more to keep the consumer economy growing: modern advertising, television, credit cards, and babies.

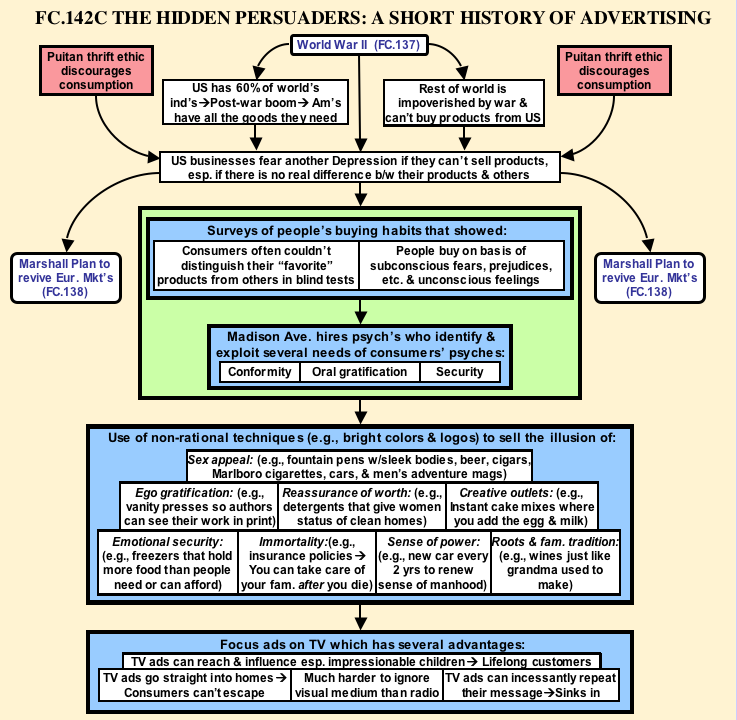

Advertising had grown in tandem with the industrial consumer economies that emerged in the nineteenth century. As production of goods grew, so did the need to find consumers to buy those goods. After World War II, this need grew dramatically in the United States which, having suffered little material damage from the war, had 60% of the world’s industrial capacity and needed to convince people to buy those goods. Complicating this was the traditional thrift oriented mentality of most people, especially reinforced by the hard times of the recent Depression. In addition, there was little to qualitatively distinguish one brand of product from another.

Therefore advertising agencies hired psychologists who used modern psychological techniques to influence people to subconsciously prefer their products over the virtually identical products of their competition. One of the big pioneers in this field was Rosser Reeves, best known for his Anacin commercials that showed annoying animated images of hammers pounding and throbbing brains to get people to buy his product for their headaches. People hated these commercials, but they also bought lots of Anacin. Other commercials attacked people’s subconscious fears and insecurities to make them believe their products, such as a brand new car, would solve their problems. Vance Packard exposed these tricks in his book, The Hidden Persuaders, but people still kept buying.

Adding a whole new dimension to these advertising techniques was television, which mesmerized people with dynamic moving images designed to sell them the sponsors’ products. Television was the perfect advertising tool for reaching a visually oriented species such as humans whose eyes take in 90% of the information they get from the world around them. Reinforcing these messages were shows that typically showed affluent families with the very sorts of products the sponsors wanted viewers to buy.

Unfortunately, buying all this cost more money than people had saved in cash. So along came the credit card, making it easy for people to get that new car or washing machine now and worry later about paying for it (along with added interest charges). Credit cards did indeed encourage consumer spending. Unfortunately, millions of families also found out how easy it was to lose track of their spending and fall heavily into debt.

Finally, there was the post-war baby boom that put pressure on parents to provide their children with a better life than they had during the Depression. In the consumer society of the 1950s, people equated this with buying lots of toys and other things for their children. And that could only be good for business. These new opportunities and pressures affected people’s attitudes toward two things: conformity and sex.

Conformity and deformity

Both men and women experienced growing frustration with pressures to conform. However, they experienced them in different ways. After the war, millions of men seemed to move seamlessly from the regimentation and conformity of the armed forces to that of the corporations that were rapidly growing with the American economy. However, although corporate regimentation seemed familiar enough to these men, the lack of excitement and sense of purpose they had known during the war was gone. Replacing it was a dull routine of paperwork, meetings, and kow-towing to the boss. Reflecting this lack of purpose was a profusion of adventure magazines that tried to recapture the excitement of the war years. Also reflecting itwas Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1955), a book detailing the frustrations of being trapped in the corporate rat race by day, only to return every evening to a house in the suburbs that was increasingly less a home and more a burdensome means of keeping up with the Joneses. Its characters, Tom and Betsy Rath were fictional, but the life they portrayed was all too real to growing numbers of Americans in the 1950s.

For women much of the problem started with an acute post-war housing shortage that developed when millions of veterans came home, got married, and started families. The solution to this problem was a brand new phenomenon: the suburbs. The suburbs were largely the invention of William J. Levitt who applied Henry Ford’s mass production techniques for cars to building homes. He broke home construction into 27 separate steps, each one being handled by a separate team specializing in that step. By 1948, Levitt’s crews were completing 36 houses a day. Each house sat on a lot of 60 by 100 feet and had two bedrooms a bathroom, a 12 by 16 foot living room, and a kitchen. They had no basements, because concrete slabs were much easier and faster to lay down. The first Levittown, as this Long Island community was called, had 17,000 such houses with 82,000 residents.

Mass-produced Levittowns solved the acute post-war housing shortage, but they also created a whole new set of problems for women: isolation. Since the men generally took the family car on their long daily commutes between home and work (another source of stress), their wives were stranded miles away from their families and friends they had grown up with in the city. Instead of apartment buildings shared by a number of families, there were now separate family homes, oftentimes separated from one another by fences. The meaningful relationships and mutual support women had previously relied on were now replaced by a growing sense of desperate isolation from the rest of the world. This malaise was given a name, Housewife Syndrome, and a cure, large doses of anti-depressants to medicate women into passive acceptance of their fates. For both men and women, alcohol consumption also increased dramatically in order to dull the pain.

One woman who had bought into the suburban dream and seen it go sour was Betty Friedan. Coming to a gradual realization that millions of other women shared her malaise, she wrote a book that took her five years to research and write. That book, The Feminine Mystique (1963), would become the handbook for the feminist movement gradually coming together in the 1960s.

Things we don’t talk about

That was the general attitude of society toward sex before the 1950s. Underwear was referred to as unmentionables and talk about sex reverted to discussing birds and bees. Enter Alfred Kinsey, a mild straight-laced professor at Indiana University with a passion for collecting things, especially knowledge. In the 1940s Kinsey launched a monumental study that culminated in 1947 with the publication of Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, an 804 page, three-pound book that quickly became a bestseller. Kinsey’s book showed that pre-marital sex, extra-marital sex, homosexuality, and other practices typically labeled deviant behavior were more prevalent and normal for men than previously assumed. Naturally, such findings triggered heavy criticism and moral outrage from parts of a society still deeply rooted in its Protestant heritage. Not surprisingly, Kinsey’s next book, Sexuality in the Human Female (1953), sparked an even more violent backlash, since it was about our mothers, sisters, daughters, and wives who were supposed to be pure and basically asexual. More devastating to Kinsey was The Rockefeller Foundation’s decision to cut funding for his research. Kinsey’s reaction was to overwork himself in further pursuit of his research until he died of heart failure in 1956. But the cat was out of the bag.

Kinsey’s work encouraged more open attitudes toward sex. Much of this was healthy, but there were some results of questionable value. Most notable among these was Hugh Hefner’s Playboy magazine, which showcased glossy airbrushed photos of beautiful women who evoked images of the wholesome girl next door except that they happened to be missing their clothes. Hefner, himself from a strict Methodist background, espoused a philosophy of promiscuous sex divorced from any emotional commitments. All this was slickly wrapped in a package laced with product placement type articles/ads for the latest accessories for the successful playboy: cars, stereos, clothes, etc. There were also serious articles and interviews that Hefner’s customers could conveniently claim they bought the magazine for. The cumulative effect of this approach was to give pornography a pseudo respectability that made it and sex part of the mainstream culture.

Meanwhile a very different sort of quest was being realized: the birth control pill. The driving force behind the pill was Margaret Sanger. For decades she had been crusading to get access to birth control for women suffering in poverty from the burden of too many children. Sanger, an incredibly persistent woman, had been jailed several times just for providing information about birth control.. In the 1950s, she joined forces with John Pincus, whose career had suffered for his dedication to research on hormones and fertilization. Their efforts bore fruit and the birth control pill came on the market in 1960. However, the Pill, as it was called, had far-reaching and unforeseen effects. While it did relieve many women of the burden of unwanted children, it also made sex seem safer for women by removing the fear of pregnancy. Just as Playboy led a movement to bring sex out in the open for men, the Pill made sex less scary and more desirable for women. Together, Kinsey’s and Sanger’s work, Hefner’s magazine, and Pincus’ pill would help lead to the sexual revolution of the 1960s.

Conclusion: toward a decade of dissent

The 1950s are typically viewed as a placid and comfortable decade. More properly it was a transitional era seeing revolutionary changes in the home, the workplace and attitudes toward sex. Add to this the start of the Civil Rights Movement and an emerging counter-culture centered on the Beats and Rock and Roll, and one can see the seeds of dissent in the years to come.

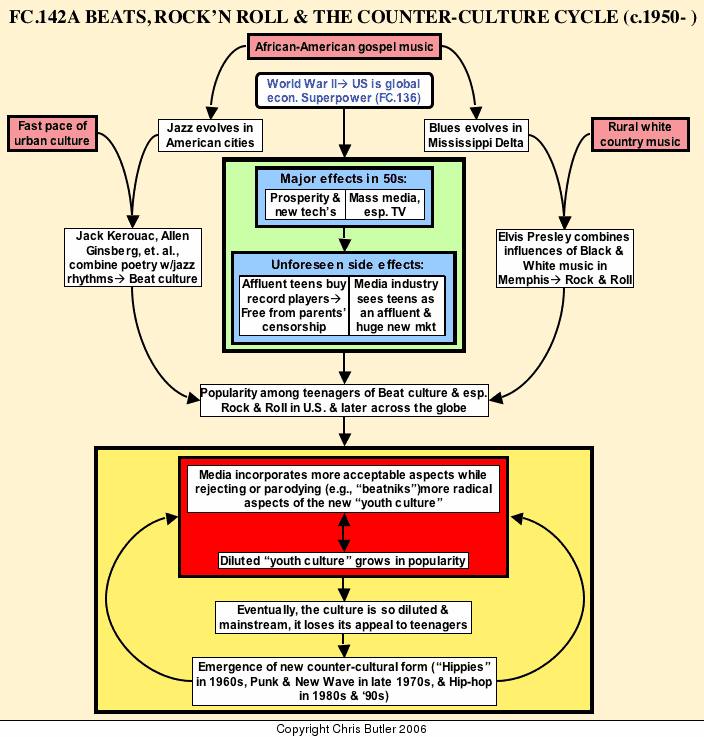

FC142AThe Beats and the Counter-culture cycle (c.1950- )

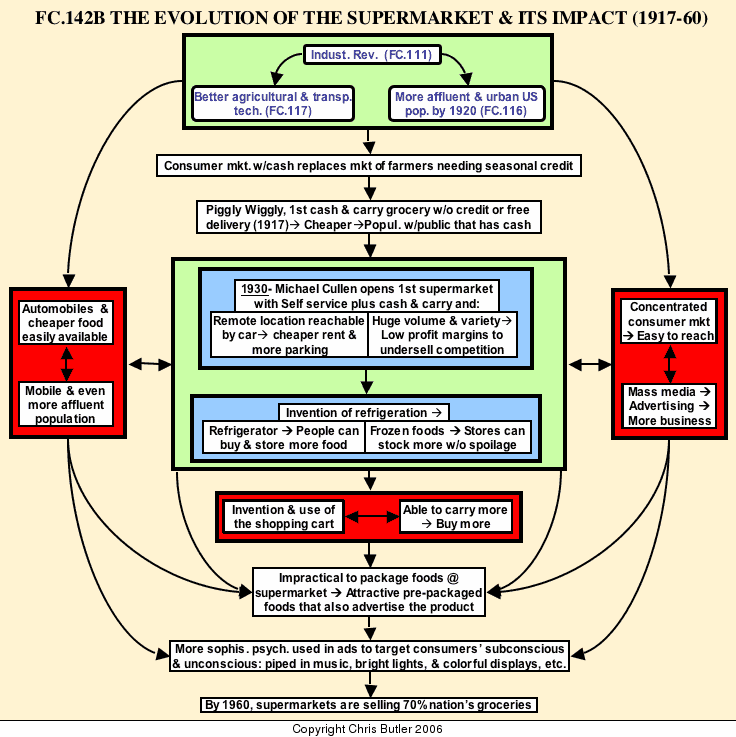

FC142BThe Evolution of the Supermarket and its impact

FC142CA Short History of Advertising

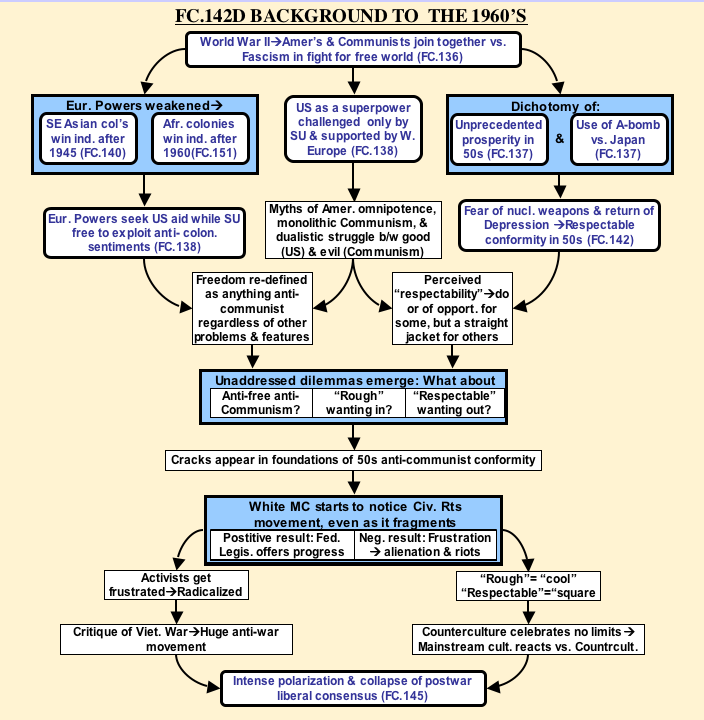

FC142DBackground to the 1960s

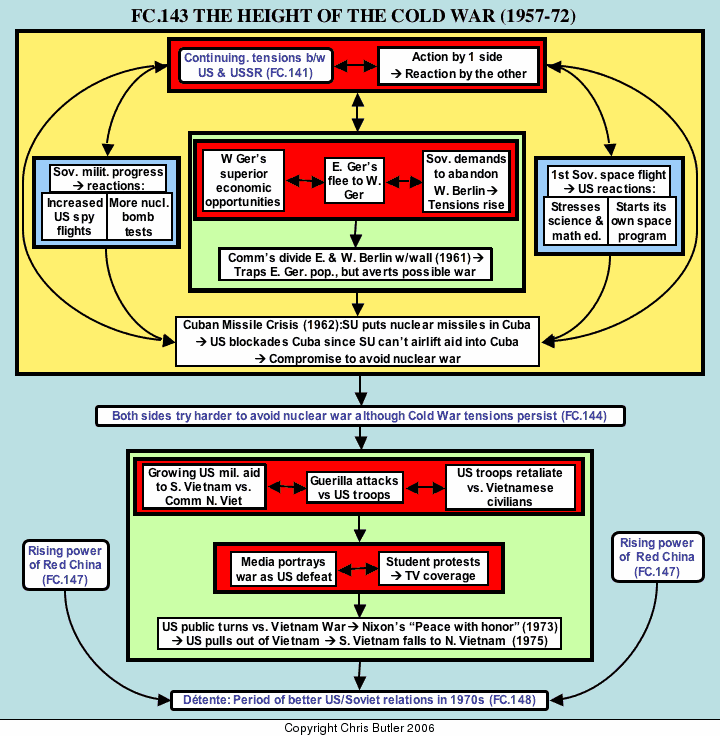

FC143The Height of the Cold War (1957-72)

Rising tensions

As we have seen, Khrushchev’s efforts to ease East-West tensions were unable to overcome the inertia of Stalin’s legacy. Therefore, relations between the two super-powers continued to deteriorate into the 1960s, as one side’s actions would lead to a reaction by the other side, which would only trigger a reaction by the first side and so on. The following years would see the United States and Soviet Union competing in two ways: military build-ups and a new phenomenon, the space race.

In the 1950s the Soviets developed the Bison Bomber and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), both of which could deliver nuclear weapons to the United States. The American public became increasingly concerned about the so-called “bomber gap.” Reaction to this was two-fold. For one thing, the U.S. increased testing of nuclear weapons as a way to flex its muscles. Unfortunately, the Soviets did the same,

Secondly, the U.S. increased its spy flights over the Soviet Union to determine how large the “bomber gap” was. Such a gap did indeed exist, but it was in America’s favor. However, the top-secret nature of his information and how it was obtained kept President Eisenhower from silencing Democrats who criticized him for being soft on defense. His situation was further complicated in 1960 when a U-2 spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. Khrushchev was furious and had the American pilot, Gary Powers, publicly tried and sentenced to ten years imprisonment.

While Eisenhower had to worry about concealing how much he knew about Soviet defenses, Khrushchev also had to worry about how much the U.S. knew, in particular how vulnerable the Soviet Union was. Therefore, he increased Soviet nuclear testing to deflect public attention, detonating a 57-megaton H-bomb (1961), the largest man-made explosion in history. Increased nuclear testing by both sides accomplished nothing except for increasing worldwide concern about the higher levels of radiation being released into the atmosphere. Meanwhile, Khrushchev had one more ace up his sleeve: Sputnik.

On October 4, 1951, the Russians launched Sputnik, the world’s first space satellite, into orbit around earth. Although it was only a small metal ball emitting a weak radio signal, it shocked Americans who saw this as a threat to their security. Once again, the response was two-fold. In 1958 Congress passed the National Defense Education Act. From this point on, American schools would stress math and science in their curriculum in order to compete with Soviet science and technology.

The second American response was to launch its own space program. After an embarrassing initial failure, the Americans launched their own space satellite in 1958. The Space Race was on. Over the next decade, the two powers competed to achieve the first manned space flight, the longest space flights, the first walk in space, the first manned orbiting of the moon, and ultimately the first lunar landing. On July 16, 1969, millions of Americans watched a live broadcast of the first human to walk on the moon. Although the space race itself accomplished little of value, it spawned a technology revolution, especially in communications as television broadcasts and telephone calls could now span the globe.

The Berlin Wall

Ever since 1945, the West’s control of West Berlin had presented major problems, since it was situated in the middle of East Germany with several very vulnerable routes there from West Germany. In 1948, Stalin had tried to gain control of West Berlin by cutting off its land corridors to the West, but the Americans and British had successfully air-lifted supplies into the beleaguered city until Stalin gave in. However, West Berlin continued to present a growing problem for the Soviets, since it was a constant reminder to East Germans all around of the much better standard of living in the West. Complicating this was the fact that there was free access between East and West Berlin. This and the lure of a better lifestyle caused growing numbers of East Germans to defect to the West, which only hurt the East German economy more and made the West that much more enticing. This led to Soviet demands for the West to abandon West Berlin, but this only increased tensions that drove even more East Germans to flee to the West and so on.

People worried that Berlin would be the spark to ignite World War III. Then, on August 13, 1961, Berlin awoke to find the East Germans building a wall to cut off all access between the two parts of the city. Despite public indignation, Western leaders breathed a sigh of relief, because the Berlin Wall solved the problem of mass defections to the West without damaging their prestige. However, the Berlin Wall would separate families for nearly thirty years and stand as the most visible symbol of the Cold War until its fall on November 9, 1989.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

For years, Cuba had suffered under the corrupt dictatorship of Juan Batista while serving as a playground for rich Americans. In the 1950s Fidel Castro started a small insurgency that gradually grew into a full-fledged revolution and overthrew Batista in 1959. Although Castro had socialist leanings, he was not a declared communist. However, the United States, in the midst of the Cold War, tended to see red when any leader with the slightest socialist leanings appeared in the Western Hemisphere. When it refused to recognize Castro’s regime, he formed closer ties with Russia. The U.S. responded by refusing to refine imported Soviet oil in its Cuban refineries, spurring Castro to nationalize those refineries. When the U.S. put an embargo on all Cuban goods, Castro retaliated by nationalizing all American owned businesses in Cuba. Then it turned nasty, with the CIA launching air raids on Cuban sugar fields and plotting against Castro by putting chemicals in Castro’s cigars to make his beard fall out and spraying LSD into a studio he was visiting to make him act crazy. Finally, Castro declared his movement a communist revolution.

Under Eisenhower, the CIA had organized an invasion of Cuban émigrés to overthrow Castro. However, in 1961, a new president, John F. Kennedy, took office. When presented with the CIA’s plan for an invasion, he agreed to go ahead with it, but cut critical American air support, fearing to expose American involvement in this plan. Consequently, the ensuing Bay of Pigs invasion was an unmitigated disaster that embarrassed Kennedy and infuriated Castro. Khrushchev convinced Castro to let him put medium and intermediate range missiles armed with nuclear warheads in Cuba. For the first time in the Cold War, most American cities were within range of Russian missiles. Therefore, when American U-2 spy planes spotted these missiles in October 1962, Kennedy treated this as a major threat.

The question was how to get rid of the missiles. Just as appeasement had led to World War II in 1939, a mere diplomatic response seemed too mild and ineffective for this situation. By the same token, while the generals pressured Kennedy to invade Cuba or launch an air strike against the Soviet missiles, he remained acutely aware that such aggressive actions could trigger a third world war and nuclear holocaust. (At the time, Kennedy was reading Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August that told how aggressive diplomatic actions had led to World War I.) Along those lines, he saw that it was unclear as to who was the “home team” defending its turf, because, while Cuba was geographically closer to the U.S., it was firmly allied with the Soviet Union.

He finally decided on the strong but less provocative course of a naval blockade to stop more Soviet missiles from reaching Cuba. While the United States and Britain had been able to airlift supplies into West Berlin over Stalin’s blockade in 1948-9, airlifting heavy missiles into Cuba over such a long distance was not an option for Khrushchev. A few days later, the policy bore fruit when an approaching Soviet convoy turnedback rather than trying to crash the American blockade. However there was still the much stickier issue of how to remove the missiles already in Cuba.

By late October tensions were near breaking point as the American military moved to Def-Con 2, signaling that war seemed imminent. Civilians made plans to evacuate major cities that might be targeted for a nuclear strike. The military was pressuring Kennedy to invade Cuba, unaware that the Soviets had tactical nuclear weapons on Cuba that would have immediately destroyed any invading force. Just to add to the tension, on several occasions false alarms nearly launched our bombers. Then Kennedy received two messages from Moscow, one fairly conciliatory, the other more provocative. Such mixed signals further confused him about the proper response, there even being speculation that a military coup had seized power in the Kremlin in the interim between the two messages. Kennedy decided to respond to the more conciliatory message and ignore the other one, thus establishing a calmer basis for negotiation. On this basis he struck a deal with Khrushchev. Russia would publicly remove the missiles in return for an American promise not to invade Cuba. Privately, Kennedy agreed to remove American missiles from Turkey that posed a similar threat to Russia. Therefore, publicly it seemed that the U.S. had won, while behind the scenes the net result was that fewer missiles threatened Russia than before 1961 and no more missiles threatened the U.S.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a major turning point in the Cold War. It was the closest we ever came to unleashing a nuclear holocaust that would have devastated civilization. Both sides clearly saw this and worked harder to avoid such a scenario. They installed the “Hot Line” to ensure better communications between the two sides and avoid unnecessary speculation, such as whether the other side had had a military coup. In 1963, the two sides agreed to a ban on atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, thus putting an end to such ridiculous saber rattling. The Cold War would continue for almost another thirty years, but the two sides had planted the seeds of at least some level of mutual trust that would form the basis of more substantial progress in the years to come.

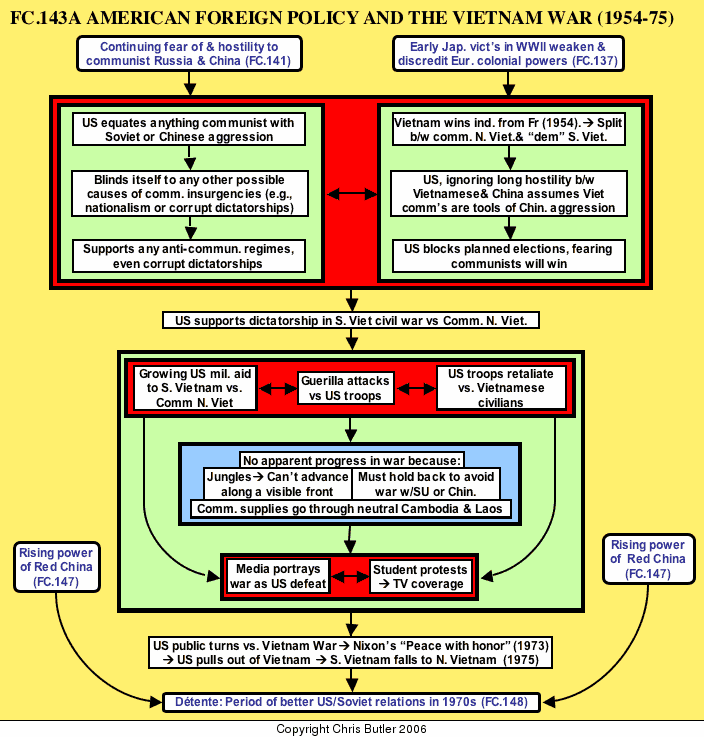

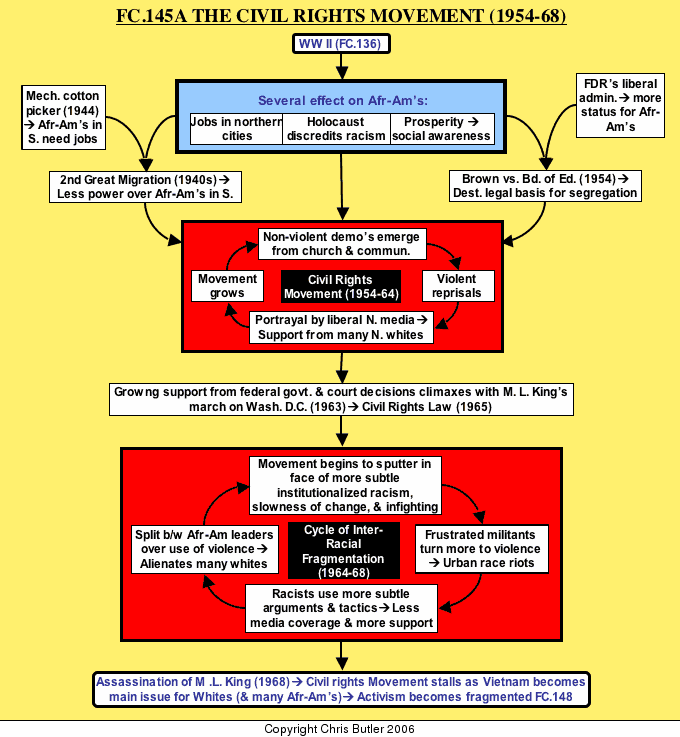

Vietnam (1954-75)

Since the 1880s Vietnam had been part of a larger French colonial holding known as Indo-China. After World War II a popular revolt with strong communist elements broke out which eventually surrounded and defeated French forces at Dien Bien Phu, and won independence in 1954. Vietnam was divided between North and South at the 17th parallel, with planned elections to reunite the country in 1956. However, The United States, fearing a communist victory, prevented the elections from taking place, thus keeping Vietnam divided between the communist North and a “democratic” South that actually functioned under a series of American-backed dictators. Civil War soon erupted with North Vietnam supporting a communist insurgency known as the Viet Cong in the South.

The U.S. viewed this struggle in purely Cold War, communist vs. capitalist, terms, ignoring its more nationalist character,. This blinded it to two important facts. One was that the government it supported in Saigon (the South Vietnamese capital) was a brutal dictatorship and anything but democratic. Secondly, ignoring the centuries-long animosity between the Chinese and Vietnamese, it saw North Vietnam as a pawn in a Chinese plot to to conquer all of Asia.

Acting on these assumptions, the U.S. felt it imperative to support the government in Saigon against the Viet Cong and North Vietnam. At first, Eisenhower sent only a few hundred military advisors and Kennedy slightly increased this commitment. However, it was President Johnson who heavily committed American forces and aid to South Vietnam in the 1960s.

Unfortunately for American forces, this was very different from any war they had ever fought in before. Instead of the traditional head-on clashes between clearly identifiable armies, this was a guerilla war where insurgents would attack American soldiers and then melt back into the civilian population, often making it impossible to identify and catch them. Out of frustration, American troops would retaliate against any civilians in the area of the attack, inevitably killing innocent people in their efforts to find the Viet Cong. This would increase public support for the Viet Cong and feed more guerilla attacks which, in turn, would trigger both increased American involvement in Vietnam and more retaliation against innocent civilians, and so on. Vietnam’s jungles also made it virtually impossible for American forces to sweep through the countryside or even effectively disrupt enemy supply lines, known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This trail ran largely through neighboring Cambodia and Laos to avoid American attacks, unless the U.S. wanted to complicate its situation further by sending forces into those countries.

Another factor in this war was television coverage. This was the first television war, where Americans would watch updated accounts and images of the war every night on the evening news. This can make progress in any war seem unbearably slow, but especially so in Vietnam where the nature of the fighting eliminated the traditional measure of success: geographic advance along a front towards a stated goal, typically the enemy capital. However, there were no geographically defined fronts in this war, only isolated raids where American troops would be airlifted by helicopters into remote villages, try to identify and catch the enemy, and then get airlifted out, abandoning control of the villages to the enemy once again. This daily repetition of seemingly identical raids with no apparent progress or purpose increasingly frustrated the American public.

Added to this frustration was the media’s portrayal of the war as a losing cause, especially after the Tet Offensive in 1968. This was a surprise attack that did catch U.S. and South Vietnamese forces off guard, but turned into a major defeat for the communists. However, the media’s portrayal of this battle as a defeat (because of its initial surprise) turned much of the American public against the war. This generated another vicious cycle where media portrayal of the war as a losing cause would trigger student protests that also got heavy TV coverage. These would reinforce the media’s negative portrayal of the war, causing more protests and so on.

The war’s unpopularity forced President Johnson out of the presidential race in 1968. The winner was Richard Nixon who told the public he had a secret plan for ending the war while he was secretly telling the North Vietnamese to keep fighting while Johnson was still in office, saying they could get a better deal with him if he were elected. When Nixon took office, he pushed for “Vietnamization” of the war, replacing American troops with South Vietnamese conscripts, many of who proved unreliable in the fight to defend a corrupt and failing dictatorship. However, this gave Nixon the chance to negotiate a “peace with honor” (1973), which left communist forces still operating in South Vietnam intact, but gave American forces enough time to exit Vietnam before the Saigon government fell. In 1975, North Vietnamese forces entered Saigon, thus reuniting Vietnam. Three years later, as if to underscore the nationalist nature of this prolonged struggle and debunk the idea that the war was a Chinese plot, Chinese and Vietnamese forces were firing at each other as they had for centuries.

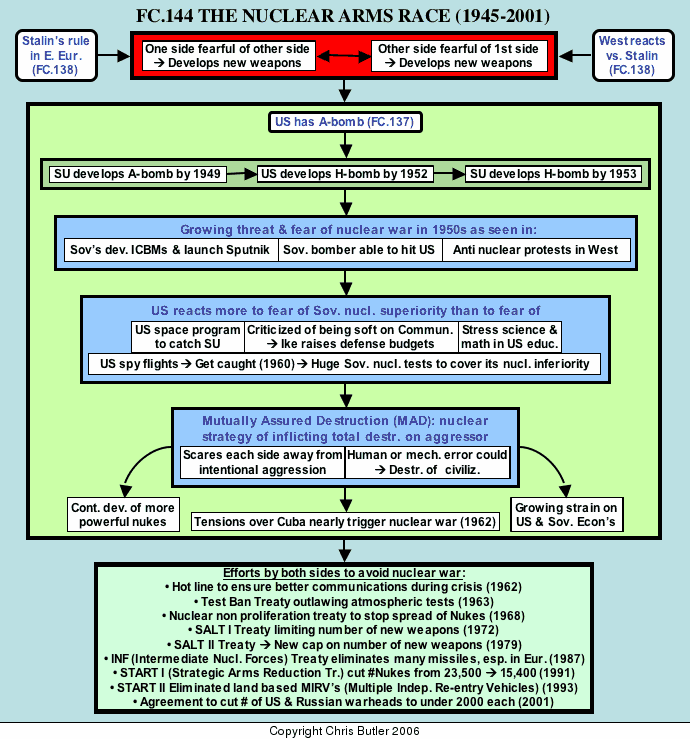

FC144The Nuclear Arms Race (1945-2001)

Introduction

We have already seen how Stalin’s domination of Eastern Europe after World War II and the West’s reaction to his aggression led to a vicious Cold War cycle of one side, fearful of the other, developing new weapons, which caused the other side to do the same and so on. Of course, the single factor making the Cold War so unique and dangerous was nuclear weapons. And just as the Cold War’s roots lay back in World War II, so did the roots of the nuclear arms race.

Starting in 1942, almost immediately after its entry into World War II, the United States had worked intensively to develop an atomic bomb before Nazi Germany could do the same. On July 15, 1945 the American program, known as the Manhattan Project, successfully tested the first nuclear bomb at Almogordo, New Mexico. The United States expected to keep its monopoly on the atomic bomb well into the 1950s, by which time its nuclear arsenal would be virtually impossible for anyone else to match or threaten. However, the Stalin’s scientists, thanks partly to espionage reaching into the ranks of the Manhattan Project, successfully developed and tested their own atomic bomb in 1949. The Americans, desperate to regain their technological edge to counterbalance Stalin’s huge conventional forces, decided to work on what was referred to as the Super bomb. This device, also known as a hydrogen bomb, would create a fusion reaction to trigger a thermonuclear explosion as much more powerful than the atomic bomb as that bomb was compared to the conventional bombs used in World War II. In 1952, the United States successfully developed and tested such a fearsome weapon. However, the Russians, following the same line of research, produced their own super bomb in 1953, only a year after the Americans had done the same.

As a result, both the threat and fear of nuclear war grew throughout the 1950s as evidenced by several things. For one thing, despite the death of Stalin in 1953 and the opportunity for better American-Soviet relations, tensions continued and even grew. Also Soviet military technology seemed to surpass that of the Americans, especially in the realm of delivery systems. In 1957, they developed the first Intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of delivering nuclear warheads to targets in the United States when fired from Soviet territory. The same year, the Soviets launched the first space satellite, Sputnik, raising American fears of the Russians launching nuclear attacks from outer space. Also, the Russians started developing their first long-range bomber force, another area where the United States previously had a monopoly. Finally, as nuclear arsenals grew and with them the threat of nuclear Armageddon, an anti-nuclear movement emerged in the West.

However, in the late 1950s the arms race combined with continuing Cold War rhetoric made the American public even more afraid of growing Soviet military power than nuclear holocaust. As a result, President Eisenhower, under increasing criticism for being soft on communism, increased military spending, which only brought a similar reaction from the Soviet Union. Ironically, he did this knowing (through top secret information that he could not make public) that the feared “bomber gap” actually heavily favored the United States. Along these lines the United States embarked on an expensive space program to close the “space gap” and reoriented its school curricula to emphasize math and science in order to close the perceived “education gap”.

Finally, the U.S. tried to close the “espionage gap” by increasing spy flights over Russia to compensate for the fact that it was easier for the Soviets to infiltrate America’s open society with spies than it was for the U.S. to do the same into the much more tightly closed Soviet society. Unfortunately, in 1960 an American U-2 spy plane was shot down over Russia and its pilot, Gary Powers, was captured. In addition to the diplomatic furor this raised, it also alarmed Khruschev about how much the Americans knew concerning Russia’s relative nuclear weakness. In order to cover this up, he ordered a series of massive atmospheric tests of Hydrogen bombs as a warning to the West. The U.S. responded in kind and nuclear tensions (and fallout) continued to increase into the 1960s.

MAD

Out of this situation evolved the dominant nuclear strategy of the Cold War: mutually assured destruction (MAD). The basic idea was that each side built up such an overwhelming amount of nuclear firepower (known as overkill) that no one would dare launch a war out of fear of massive retaliation. The basic psychological assumption MAD was sound, because it did scare each side away from intentional aggression that might lead to an all-out thermonuclear exchange. However, there was the danger that human or mechanical (especially computer) error could accidentally trigger World War III. Growing fears of such a scenario were reflected in several books and movies of the era, notably Fail Safe and Doctor Strangelove. In fact, there were several incidents where some sort of mechanical error did nearly launch a nuclear war. Fortunately, in each case disaster was averted, typically by an individual who refused to believe the launch orders were real.

MAD produced several results that together seemed to be both hurtling the human race toward certain destruction and bringing it to its senses. For one thing, MAD demanded that each side keep a large retaliatory (second strike) force that could survive a surprise attack by the enemy and act as a deterrent to such an attack. Therefore, both sides continued to build huge nuclear stockpiles and progressively more accurate delivery systems that gave them the combined capability of destroying the human race many times over.

However, despite the perception that nuclear weapons were more cost effective than conventional weapons, providing more “bang for the buck”, so to speak, they were also prohibitively expensive. This was especially true for the research and development of new weapons systems, since the arms race catalyzed increasingly high-tech research that became more costly as the technology involved became more sophisticated. Eventually, the huge price tag of the arms race would drive the Soviet Union into financial oblivion and help end the Cold War. However, that would not happen until the 1980s. In the 1960s, it was a more immediate crisis that would help cool down the arms race: the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Gradually defusing the nuclear time-bomb (1962-2001)

The realization of how close we had come to World War III over Cuba woke many people to the dangers of thermonuclear war. As a result, both sides were much more careful to take precautions to avoid such a disaster. The major obstacle to overcome was the deep distrust between the Soviets and Americans. Therefore, bringing the nuclear genie under control involved starting with relatively small measures to gradually build mutual trust as a foundation for more substantial measures. The first such step was installing the Hot Line, a direct phone line between Washington and Moscow that would speed up communications and reduce the chances of a garbled misunderstood message triggering an unintended war. Along these lines, both sides were constantly upgrading their control systems to minimize the chances of some officer or mechanical error launching World War III without authorization from above. In 1963 came an atmospheric test ban treaty to protect the atmosphere from fallout. In 1968 the nuclear non-proliferation treaty committed a large number of nations to not developing nuclear weapons.

In the 1970s, the United States and Soviet Union took a giant step forward with the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaties, SALT I (1972) and SALT II (1979), which put caps on the number of new weapons being produced. Although this did not stop the spiraling arms race, at least it put some limits on it and kept both sides talking. Unfortunately, during the 1980s, the Cold War heated up again, and with it the arms race. However, by this time, high tech, especially computer technology, was making possible a whole new generation of sophisticated weapons systems, including the possibility of mounting a guided missile defense system against an incoming nuclear attack. President Reagan’s proposed Strategic Defense Initiative (AKA “Star Wars” or SDI), although. Technologically unfeasible at the time, still upped the stakes (and price tag) of the arms race. By this time, the Soviet Union’s economy was already sinking under the burden of trying to keep up with the United States’ buildup. Therefore, its new leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, announced a unilateral withdrawal of some Soviet forces from Eastern Europe as a gesture to the West for more substantial talks. These renewed disarmament negotiations produced a series of new treaties that significantly reduced nuclear stockpiles and ended the Cold War on a much happier note than it might have:

• Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty eliminates many missiles, especially in Europe (1987)

• Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) cut number of Nuclear warheads from 23,500 à 15,400 (1991)

• START II Eliminated land based MIRV’s (Multiple Independent Re-entry Vehicles) (1993)

• Agreement to cut American & Russian nuclear forces below 2000 warheads each (2001)

The arms race between the Cold War superpowers ended much better than it might have. That’s the good news, that human beings are capable of resolving their differences peacefully. However, we’re not out of the woods yet as other people try to get and intend to use “weapons of mass destruction”. Still, the final lesson of the Cold War is that there is still hope, and that, as always, is a priceless commodity.