The Age of ExplorationUnit 12: The Age of Exploration (c.1400-1900)

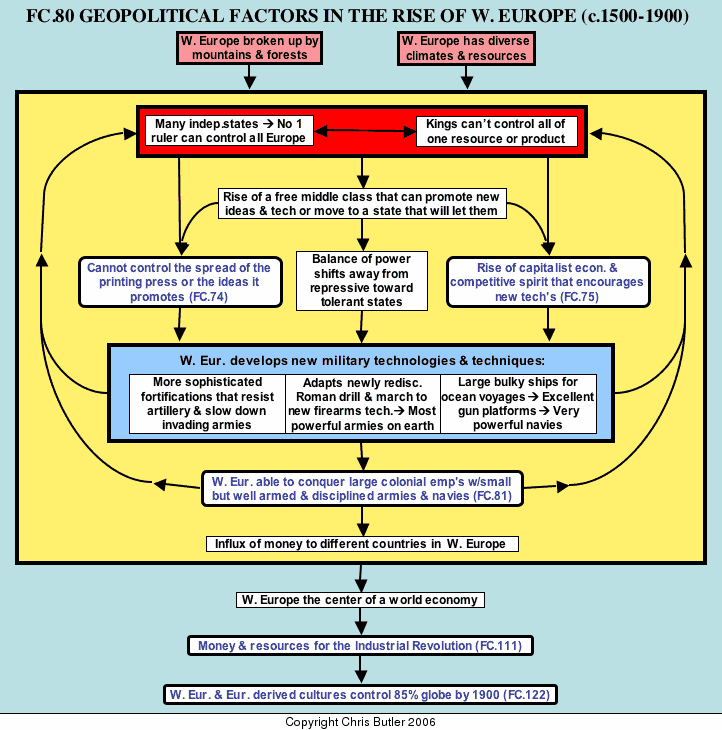

FC80Geopolitical factors in the rise of Europe

Introduction

The four centuries following 1500 would see the meteoric rise of Western Europe from a cultural backwater to the first culture to dominate the planet. Given Western Europe's tiny size, the question arises: what singled it out as the civilization to rise to global dominance? A century ago, Europeans would attribute their dominance to the moral and religious superiority of European and Christian culture. However, life and history are not quite so simple. Rather, there was a unique combination of forces that converged at the right time and place to make European civilization the culture that would largely define the modern world, especially in terms of its technology and political ideologies.

On the surface, other civilizations seemed more likely to predominate, having larger populations, strongly centralized governments, wealth, and technologies comparable to, if not greater than, Western Europe's. For example, Ming China had a population two to three times that of Western Europe. Traditionally, Chinese technology had been among the most innovative in the world, heavily influencing Europe itself with such inventions as gunpowder, the clock, paper, and the compass. China's government was strongly centralized and autocratic, being run by what was probably the best civil service in the world at that time.

The other major civilizations in the world, such as the Ottoman Turks, Mughal India, Tokugawa Japan, Muscovite Russia, and the Incan and Aztec Empires in the Western Hemisphere, told a similar story of being populous, wealthy (except for Russia), and highly centralized under strong autocratic rulers. In fact, it was Western Europe's lack of autocratic rulers, such as these other cultures had, which would be the key to its leaping ahead of the pack. For, while the absolute rulers outside of Europe tended to exploit and suppress their middle class and, in the process, stifle inventiveness and initiative, the spirit of free enterprise and inventiveness had much more free rein in Western Europe. That freedom created a powerful dynamic that allowed Europeans to forge ahead with new ideas, business techniques, and technologies that would shape the modern world. And if freedom was the key to Europe's success, geography was much of its underlying basis.

Europe's geography and its effects

There were two main geographic factors that would help lead to Western Europe's later dominance. First of all, Western Europe was broken up by mountains, forests, and bodies of water: the Alps and Pyrenees cutting Italy, Spain, and Portugal off from northern Europe; the English Channel cutting England off from the continent; and the Baltic Sea separating Scandinavia from the rest of Europe in the south. This broke Western Europe into a large number of independent states that no one ruler had the power and resources to conquer and hold. Second, Western Europe had a wide diversity of climates, resources, and waterways which promoted a large number of separate economies, but which were linked together for trade by the extensive coastlines and river systems covering the region. Therefore, just as no one power could control all of Europe politically, no one power could monopolize one vital aspect of its economy. Thus Europe was characterized by what we call political and economic pluralism, which also reinforced each other.

Political and economic pluralism also combined to promote the rise of a prosperous and innovative middle class that could create and spread new ideas, business techniques, and technology if the local rulers would allow it. If they did not allow it, there was always the option of moving to another state that did give them the freedom to pursue their interests. The results of such moves, such as when the French Protestant Huguenots left France en masse to avoid Louis XIV's religious persecution in 1685, were to deprive the economies of the persecuting nations of some of their wealthiest and most innovative people while boosting the economies of the countries that took these immigrants in. As a result, the balance of power would constantly shift away from powerful and repressive states and in favor of the more progressive and free thinking ones, thus reinforcing political pluralism in Western Europe.

The rise of a free middle class had two other important effects. First of all, in conjunction with Western Europe's political pluralism, it could spread new technology (e.g., the printing press) and ideas (e.g., the Reformation). Second, in conjunction with Western Europe's economic pluralism, the middle class was able to create a freer capitalist economy and promote a competitive spirit that encouraged new technologies and generated profits for those with the drive and imagination to invent and sell them.

These two factors combined to generate even more rapid technological development, especially in the realm of military inventions. There were three main areas of military technology developed. First of all there was the new gunpowder technology which, when combined with the Roman drill and march recently rediscovered and revived during the Renaissance, created the most powerful and efficient armies in the world by the late 1600's. The defensive response to gunpowder gave Europe the second military factor: stronger and more sophisticated fortresses to resist artillery. These fortresses tied invading armies down to prolonged and tedious sieges that stopped, or at least drastically slowed, the progress of invading armies. One side effect of this was that it fed back into and further reinforced Western Europe's political pluralism. The third military innovation (or more properly, application of peaceful technology to military purposes) was the development of large bulky ships to withstand long voyages over the rough waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Such ships also served as excellent gun platforms, thus making European navies the most deadly on the planet.

These three factors converged to help Western Europe establish large overseas colonial empires which were conquered by Europe's small but well armed and disciplined armies and navies and held under control by powerful European fortresses. As time and Western Europe's technology progressed, European armies would show an amazing ability to defeat non-European armies many times their size with astounding regularity, each time increasing and strengthening their hold on their overseas colonies.

Europe's large colonial empires brought an influx of money and resources into Europe. This fed back into Europe's economic and political pluralism, especially after 1600 when smaller states such as England and the Dutch Republic were taking their share of overseas trade and colonies, thus starting the cycle all over again. These colonial empires also made Western Europe the center of a world economy, providing it with the money and resources needed for the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700's. It is no accident that the Industrial Revolution started in Great Britain, which also happened to be the foremost colonial power of its day.

Thanks to this cycle, Europe and European derived cultures (e.g., the United States, Canada, and Australia) were able to control 85% of the globe by 1900. Since then, Europe has lost its colonial empire, thanks primarily to two highly destructive world wars, but not before it could spread its ideas and technology across the globe where they have taken firm root.

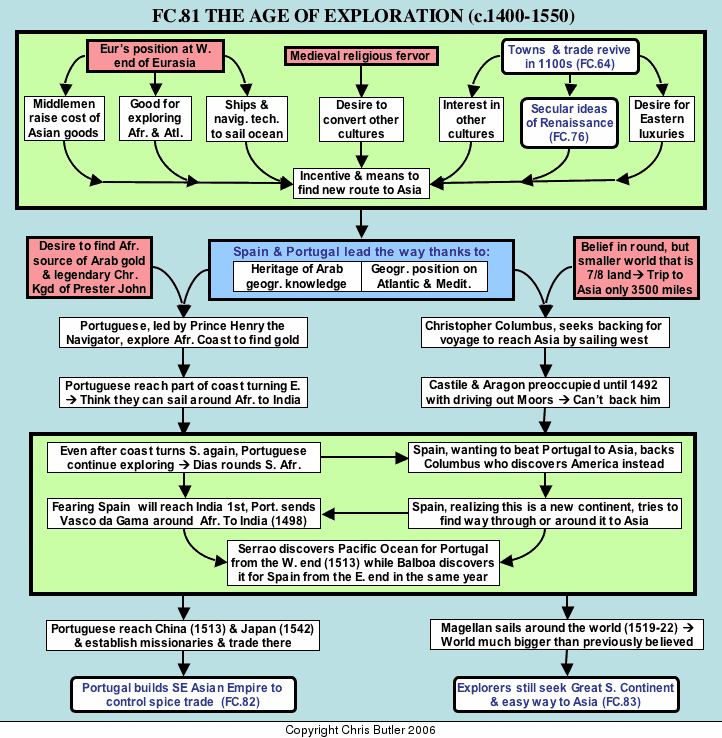

FC81Early voyages of Exploration (c.1400-1550)

Introduction

In 1400 A.D. Europeans probably knew less of the globe than they had during the Pax Romana. Outside of Europe and Mediterranean, little was known, with rumor and imagination filling the gaps. Pictures of bizarre looking people with umbrella feet, faces in their stomachs, and dogs' heads illustrated books about lands to the East. There was the legendary Christian king, Prester John with an army of a million men and a mirror that would show him any place in his realm whom Christians hoped to ally with against the Muslims.

Europeans also had many misconceptions about the planet outside their home waters. They had no real concept of the size or shape of Africa or Asia. Because of a passage in the Bible, they thought the world was seven-eighths land and that there was a great southern continent that connected to Africa, making any voyages around Africa to India impossible since the Indian Ocean was an inland. They had no idea at all of the existence of the Americas, Australia, or Antarctica. They also vastly underestimated the size of the earth by some 5-10,000 miles. However, such a miscalculation gave explorers like Columbus and Magellan the confidence to undertake voyages to the Far East since they should be much shorter and easier than they turned out to be.

Factors favoring Europe

However, about this time, European explorers started to lead the way in global exploration, timidly hugging the coasts at first, but gradually getting bolder and striking out across the open seas. There were three main factors that led to Europeans opening up a whole new world at this time.

-

The rise of towns and trade along with the Crusades in the centuries preceding the age of exploration caused important changes in Europeans' mental outlook that would give them the incentive and confidence to launch voyages of exploration in three ways. First, they stimulated a desire for Far Eastern luxuries. Second, they exposed Europeans to new cultures, peoples and lands. Their interest in the outside world was further stimulated by the travels of Marco Polo in the late 1200's.

Finally, towns and the money they generated helped lead to the Renaissance that changed Europeans' view of themselves and the world. There was an increasing emphasis on secular topics, including geography. Skepticism encouraged people to challenge older geographic notions. Humanism and individualism, gave captains the confidence in their own individual abilities to dare to cross the oceans with the tiny ships and primitive navigational instruments at their disposal.

-

Medieval religious fervor also played its part. While captains such as Columbus, da Gama, and Magellan had to rely on their own skills as leaders and navigators, they also had an implicit faith in God's will and guidance in their missions. In addition, they felt it was their duty to convert to Christianity any new peoples they met. Once again we see Renaissance Europe caught in the transition between the older medieval values and the new secular ones. Together they created a dynamic attitude that sent Europeans out on a quest to claim the planet as their own.

-

Europe’s geographic position also drove it to find new routes to Asia in three ways. First of all, Europe's geographic position at the extreme western end of the trade routes with the East allowed numerous middlemen each to take his cut and raise the cost of the precious silks and spices before passing them on to still another middleman. Those trade routes were long, dangerous, and quite fragile. It would take just one strong hostile power to establish itself along these routes in order to disrupt the flow of trade or raise the prices exorbitantly. For Europeans, that power was the Ottoman Empire. The fall of the Byzantine Empire and the earlier fall of the crusader states had given the Muslims a larger share of the trade headed for Europe. Thus Europe's disadvantageous geographic position provided an incentive to find another way to the Far East.

However, Europe was also in a good position for discovering new routes to Asia. It was certainly in as good a position as the Muslim emirates on the coast of North Africa for exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa. And when Spain gained control of both sides of the straits of Gibraltar, it was in a commanding position to restrict any traffic passing in and out of the Western Mediterranean. Europe was also well placed for exploration across the Atlantic Ocean.

Finally, ships and navigation technology had seen some dramatic leaps forward. The most striking of these was the compass, which had originated in China around 200 B.C. This allowed sailors to sail with much greater certainty that they were sailing in the right direction. Instruments such as the quadrant, crosstaff, and astrolabe allowed them to calculate latitude by measuring the elevation of the sun and North Star, although the rocking of ships at sea often made measurements taken with these instruments highly inaccurate. Columbus, one of the best navigators of his day, took readings in the Caribbean that corresponded to those of Wilmington, North Carolina, 1100 miles to the north! As a result of such imperfect measurements, sailing directions might be so vague as to read: "Sail south until your butter melts. Then turn west." Compounding this was the lack of a way to measure longitude (distance from east to west) until the 1700's with the invention of the chronometer.

Maps also left a lot to be desired. A medieval map of the world, showing Jerusalem in the center and Paradise to the Far East, gives an insight into the medieval worldview, but little useful geographic information. By 1400, there were fairly decent coastal maps of Europe and the Mediterranean, known as portolan charts. However, these were of no use beyond Europe, and larger scale global projections would not come along until the 1500's. As a result, explorers relied heavily on sailors' lore: reading the color of the water and skies or the type of vegetation and sea birds typical of an area. However, since each state jealously guarded geographic information so it could keep a monopoly on the luxury trade, even this information had limited circulation.

Advances in ship design involved a choice between northern Atlantic and southern Mediterranean styles. For hulls, shipwrights had a choice between the Mediterranean carvel built design , where the planks were cut with saws and fit end to end, or northern clinker built designs, where the planks were cut with an axe or adze and overlapped. Clinker-built hulls were sturdy and watertight, but limited in size to the length of one plank, about 100 feet. As a result, the southern carvel built hulls were favored, although they were built in the bulkier and sturdier style of the northern ships to withstand the rough Atlantic seas. One other advance was the stern rudder, which sat behind the ship, not to the side. Unlike the older side steering oars which had a tendency to come out of the water as the ship rocked, making it hard to steer the ship, he stern rudder stayed in the water.

There were two basic sail designs: the southern triangular, or lateen, (i.e., Latin) sail and the northern square sail. The lateen sail allowed closer tacking into an adverse wind, but needed a larger crew to handle it. By contrast, the northern square sail was better for tailwinds and used a smaller crew. The limited cargo space and the long voyages involved required as few mouths as possible to feed, and this favored the square design for the main sail, but usually with a smaller lateen sail astern (in the rear) to fine tune a ship's direction.

The resulting ship, the carrack, was fusion of northern and southern styles. It was carvel built for greater size but with a bulkier northern hull design to withstand rough seas. Its main sail was a northern square sail, but it also used smaller lateen sails for tacking into the wind.

Living conditions aboard such ships, especially on long voyages, was appalling. Ships constantly leaked and were crawling with rats, lice, and other creatures. They were also filthy, with little or no sanitation facilities. Without refrigeration, food and water spoiled quickly and horribly. Disease was rampant, especially scurvy, caused by a vitamin C deficiency. A good voyage between Portugal and India would claim the lives of twenty per cent of the crewmen from scurvy alone. It should come as no surprise then that ships' crews were often drawn from the dregs of society and required a strong and often brutal, hand to keep them in line.

Portugal and Spain led the way in early exploration for two main reasons. First, they were the earliest European recipients of Arab math, astronomy, and geographic knowledge based on the works of the second century A.D. geographer, Ptolemy. Second, their position on the southwest corner of Europe was excellent for exploring southward around Africa and westward toward South America.

Portugal and the East (c.1400-1498)

Portugal started serious exploration in the early 1400's, hoping to find both the legendary Prester John as an ally against the Muslims and the source of gold that the Arabs were getting from overland routes through the Sahara. At first, they did not plan to sail around Africa, believing it connected with a great southern continent. The guiding spirit for these voyages was Prince Henry the Navigator whose headquarters at Sagres on the north coast of Africa attracted some of the best geographers, cartographers and pilots of the day. Henry never went on any of his expeditions, but he was their heart and soul.

The exploration of Africa offered several physical and psychological obstacles. For one thing, there were various superstitions, such as boiling seas as one approached the equator, monsters, and Cape Bojador, which many thought was the Gates of Hell. Also, since the North Star, the sailors' main navigational guide, would disappear south of the Equator, sailors were reluctant to cross that line.

Therefore, early expeditions would explore a few miles of coast and then scurry back to Sagres. This slowed progress, especially around Cape Bojador, where some fifteen voyages turned back before one expedition in 1434 finally braved its passage without being swallowed up. In the 1440's, the Portuguese found some, but not enough, gold and started engaging in the slave trade, which would disrupt African cultures for centuries. In 1445, they reached the part of the African coast that turns eastward for a while. This raised hopes they could circumnavigate Africa to reach India, a hope that remained even when they found the coast turning south again.

In 1460, Prince Henry died, and the expeditions slowed down for the next 20 years. However, French and English interest in a route around Africa spurred renewed activity on Portugal's part. By now, Portuguese captains were taking larger and bolder strides down the coast. One captain, Diego Cao, explored some 1500 miles of coastline. With each such stride, Portuguese confidence grew that Africa could be circumnavigated. Portugal even sent a spy, Pero de Covilha, on the overland route through Arab lands to the Indies in order to scout the best places for trade when Portuguese ships finally arrived.

The big breakthrough came in 1487, when Bartholomew Dias was blown by a storm around the southern tip of Africa (which he called the Cape of Storms, but the Portuguese king renamed the Cape of Good Hope). When Dias relocated the coast, it was to his west, meaning he had rounded the tip of Africa. However, his men, frightened by rumors of monsters in the waters ahead, forced him to turn back. Soon after this, the Spanish, afraid the Portuguese would claim the riches of the East for themselves, backed Columbus' voyage that discovered and claimed the Americas for Spain. This in turn spurred Portuguese efforts to find a route to Asia before Spain did. However, Portugal's king died, and the transition to a new king meant it was ten years before the Portuguese could send Vasco da Gama with four ships to sail to India. Swinging west to pick up westerly winds, da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in three months, losing one ship in the process. Heading up the coast, the Portuguese encountered Arab surprise and hostility against European ships in their waters. Da Gama found an Indian pilot who led the Portuguese flotilla across the Indian Ocean to India in 1498.

The hostility of the Arab traders who dominated trade with India and the unwillingness of the Indians to trade for European goods which they saw as inferior made getting spices quite difficult. However, through some shrewd trading, da Gama managed to get one shipload of spices and then headed home in August 1498. It took over a year, until September 1499, to get back to Portugal, but he had proven that Africa could be circumnavigated and India could be reached by sea. Despite its heavy cost (two of four ships and 126 out of 170 men) Da Gama's voyage opened up new vistas of trade and knowledge to Europeans.

Subsequent Portuguese voyages to the East reached the fabled Spice Islands (Moluccas) in 1513. In that same year, the Portuguese explorer, Serrao, reached the Pacific at its western end while the Spanish explorer, Balboa, was discovering it from its eastern end. Also in 1513, the Portuguese reached China, the first Europeans to do so in 150 years. They won exclusive trade with China, which had little interest in European goods. However, China was interested in Spanish American silver, which made the long treacherous voyage across the Pacific to the Spanish Philippines. There, the Portuguese would trade Chinese silks for the silver, and then use it for more trade with China, while the Spanish would take their silks on the even longer voyage back to Europe by way of America. In 1542, the Portuguese even reached Japan and established relations there. As a result of these voyages and new opportunities, Portugal would build an empire in Asia to control the spice trade.

Spain and the exploration of the West (1492-c.1550)

Spain led the other great outward thrust of exploration westward across the Atlantic Ocean. Like, Portugal, the Spanish were also partially driven in their explorations by certain misconceptions. While they did realize the earth is round, they also vastly underestimated its size and thought it was seven-eighths land, making Asia much bigger and extending much further west. Therefore, they vastly underestimated the distance of a westward voyage to Asia.

This was especially true of a Genoese captain, Christopher Columbus, an experienced sailor who had seen most of the limits of European exploration up to that point in time, having sailed the waters from Iceland to the African coast. Drawing upon the idea of a smaller planet mostly made up of land, Columbus had the idea that the shortest route to the Spice Islands was by sailing west, being only some 3500 miles. In fact, the real distance is closer to 12,000 miles, although South America is only about 3500 miles west of Spain, explaining why Columbus thought he had hit Asia. The problem was that most people believed such an open sea voyage was still too long for the ships of the day.

Getting support for this scheme was not easy. The Portuguese were already committed to finding a route to India around Africa, and Spain was preoccupied with driving the Moors from their last stronghold of Granada in southern Spain. However, when the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope and stood on the verge of reaching India, Spain had added incentive to find another route to Asia. Therefore, when Granada finally fell in 1492, Spain was able to commit itself to Columbus' plan.

Columbus set sail August 3, 1492 with two caravels, the Nina and Pinta, and a carrack, the Santa Maria . They experienced perfect sailing weather and winds. In fact, the weather was too good for Columbus' sailors who worried that the perfect winds blowing out would be against them going home while the clear weather brought no rain to replenish water supplies. Columbus even lied to his men about how far they were from home (although the figure he gave them was fairly accurate since his own calculations overestimated how far they had gone). By October 10, nerves were on edge, and Columbus promised to turn back if land were not sighted in two or three days. Fortunately, on October 12, scouts spotted the island of San Salvador, which Columbus mistook for Japan.

After failing to find the Japanese court, Columbus concluded he had overshot Japan. Further exploration brought in a little gold and a few captives. But when the Santa Maria ran aground, Columbus decided to return home. A lucky miscalculation of his coordinates caused him to sail north where he picked up the prevailing westerlies. The homeward voyage was a rough one, but Columbus reached Portugal in March 1493, where he taunted the Portuguese with the claim that he had found a new route to the Spice Islands. This created more incentive for the Portuguese to circumnavigate Africa, which they did in 1498. It also caused a dispute over who controlled what outside of Europe, which led to the pope drawing the Line of Demarcation in 1494.

Ferdinand and Isabella, although disappointed by the immediate returns of the voyage, were excited by the prospects of controlling the Asian trade. They gave Columbus the title "Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Viceroy and Governor of the Islands that he hath discovered in the Indies." Over the next decade, they sent him on three more voyages to find the Spice Islands. Each successive voyage put even more of the Caribbean and surrounding coastline on the map, but the Spice Islands were never found. Columbus never admitted that his discovery was a new continent. He died in 1504, still convinced that he had reached Asia.

However, by 1500, many people were convinced that this was a new continent, although its size and position in relation to and distance from Asia were by no means clear. The Portuguese discovery of a route to India around Africa in 1498 provided more incentive for Spanish exploration. In 1513, the Spanish explorer, Balboa discovered the Pacific Ocean, having no idea of its immensity or that the Portuguese explorer, Serrao, was discovering it from the Asian side. Given the prevailing view of a small planet, many people though that the Pacific Sea, as they called it, must be fairly small and that Asia must be close to America. Some even thought South America was a peninsula attached to the southern end of Asia. Either way, finding a southwest passage around the southern tip of South America would put one in the Pacific Sea and a short distance from Asia. If this were so, it would give Spain a crucial edge over Portugal, whose route around Africa to India was especially long and hard.

In 1519, Charles V of Spain gave five ships and the job of finding a southwest passage around South America to Ferdinand Magellan, a former Portuguese explorer who had been to the Spice Islands while serving Portugal. Magellan's circumnavigation of the globe was one of the great epic, and unplanned, events in history. After sailing down the South American coast, he faced a mutiny, which he ruthlessly suppressed, and then entered a bewildering tangle of islands at the southern tip of the continent known even today as the Straits of Magellan. Finding his way through these islands took him 38 days, while the same journey today takes only two.

Once they emerged from the Straits of Magellan into the Pacific "Sea", Magellan and his men figured they were a short distance from Asia, and set out across the open water and into one of the worst ordeals ever endured in nautical history. One of those on the journey, Pigafetta, left an account of the Pacific crossing:

“On Wednesday the twenty-eighth of November, one thousand five hundred and twenty, we issued forth from the said strait and entered the Pacific Sea, where we remained three months and twenty days without taking on board provisions or any other refreshments, and we ate only old biscuit turned to powder, all full of worms and stinking of the urine which the rats had made on it, having eaten the good. And we drank water impure and yellow. We ate also ox hides, which were very hard because of the sun, rain, and wind. And we left them...days in the sea, then laid them for a short time on embers, and so we ate them. And of the rats, which were sold for half an ecu apiece, some of us could not get enough.

“Besides the aforesaid troubles, this malady (scurvy) was the worst, namely that the gums of most part of our men swelled above and below so that they could not eat. And in this way they died, inasmuch as twenty-nine of us died...But besides those who died, twenty-five or thirty fell sick of divers maladies, whether of the arms or of the legs and other parts of the body (also effects of scurvy), so that there remained very few healthy men. Yet by the grace of our Lord I had no illness.

“During these three months and twenty days, we sailed in a gulf where we made a good 4000 leagues across the Pacific Sea, which was rightly so named. For during this time we had no storm, and we saw no land except two small uninhabited islands, where we found only birds and trees. Wherefore we called them the Isles of Misfortune. And if our Lord and the Virgin Mother had not aided us by giving good weather to refresh ourselves with provisions and other things we would have died in this very great sea. And I believe that nevermore will any man undertake to make such a voyage.”

By this point, the survivors were so weakened that it took up to eight men to do the job normally done by one. Finally, they reached the Philippines, which they claimed for Spain, calculating it was on the Spanish side of the Line of Demarcation. Unfortunately, Magellan became involved in a tribal dispute and was killed in battle. Taking into account his previous service to Portugal in the East, Magellan and the Malay slave who accompanied him were the first two people to circumnavigate the earth.

By now, the fleet had lost three of its five ships: one having mutinied and returned to Spain, one being lost in a storm off the coast of South America, and the other being so damaged and the crews so decimated that it was abandoned. The other two ships, the Trinidad and Victoria, finally reached the Spice Islands in November 1521 and loaded up with cloves. Now they faced the unpleasant choice of returning across the Pacific or continuing westward and risking capture in Portuguese waters. The crew of the Trinidad tried going back across the Pacific, but gave up and were captured by the Portuguese. Del Cano, the captain of the Victoria, took his ship far south to avoid Portuguese patrols in the Indian Ocean and around Africa, but also away from any chances to replenish its food and water. Therefore, the Spanish suffered horribly from the cold and hunger in the voyage around Africa.

When the Victoria finally made it home in 1522 after a three year journey, only 18 of the original 280 crewmen were with it, and they were so worn and aged from the voyage that their own families could hardly recognize them. Although the original theory about a short South-west Passage to Asia was wrong, they had proven that the earth could be circumnavigated and that it was much bigger than previously supposed. It would be half a century before anyone else would repeat this feat. And even then, it was an act of desperation by the English captain Sir Francis Drake fleeing the Spanish fleet.

Interior and coastal explorations (1519-c.1550)

Meanwhile, the Spanish were busy exploring the Americas in search of new conquests, riches, and even the Fountain of Youth. There were two particularly spectacular conquests. The first was by Hernando Cortez, who led a small army of several hundred men against the Aztec Empire in Mexico. Despite their small number, the Spanish could exploit several advantages: their superior weapons and discipline, the myth of Quetzecoatl which foretold the return of a fair haired and bearded god in 1519 (the year Cortez did appear), and an outbreak of smallpox which native Americans had no prior contact with or resistance to. Because of this and other Eurasian diseases, native American populations would be devastated over the following centuries to possibly less than ten per cent their numbers in 1500.

The Spanish conquistador, Pizarro, leading an army of less then 150 men, carried out an even more amazing conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru in the 1530's. Taking advantage of a dispute over the throne, Pizarro captured the Inca Emperor, whose authority was so great that his capture virtually paralyzed the Incas into inaction. As a result, a highly developed empire ruling millions of people fell to a handful of Spaniards.

The conquests of Mexico and Peru more than compensated Spain for its failure to establish a trade route to the Spice Islands. The wealth of South America's gold and silver mines would provide Spain with the means to make it the great power of Europe in the 1500's. Unfortunately, Spain would squander these riches in a series of fruitless religious wars that would wreck its power by 1650.

Other Spanish expeditions were exploring South America's coasts and rivers, in particular the Amazon, Orinoco, and Rio de la Plata, along with ventures into what is now the south-west United States (to find the Seven Cities of Gold), the Mississippi River, and Florida (to find the Fountain of Youth). While these found little gold, they did provide a reasonable outline of South America and parts of North America by 1550. However, no one had yet found an easy route to Asia. Therefore, the following centuries would see further explorations which, while failing to find an easier passageway, would in the process piece together most of the global map.

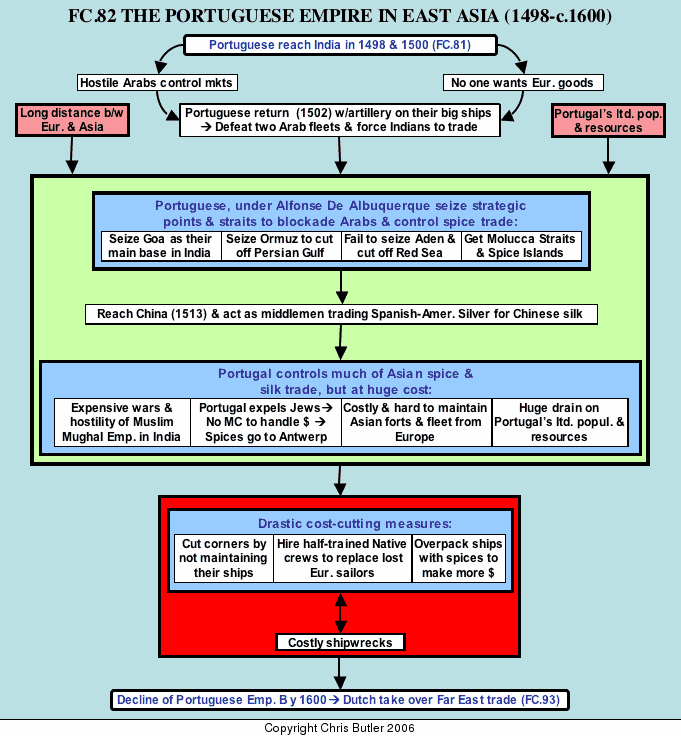

FC82The Portuguese Empire in the East (c.1500-1600)

Even before da Gama had set out for India, a Genoese explorer sailing under the Spanish flag, Christopher Columbus, had returned from what he believed was a direct route to Asia. This provoked a dispute between Spain and Portugal over who could claim what territories outside of Europe. In 1494, the pope arbitrated the dispute and drew a Line of Demarcation down the middle of the Atlantic. Everything outside of Christian Europe and west of the line belonged to Spain; everything east of it was Portugal's to claim. The line extended all around the globe, but since the size of the earth was not known, just where that line came out was anybody's guess. Despite these uncertainties, the Pope's Line of Demarcation determined the direction of both Spanish and Portuguese explorations. For the Portuguese, this meant they must control the trade routes to the East.

In 1500, only a year after da Gama's return, Pero Alvares Cabral followed da Gama's route to India with a fleet of ten Portuguese ships. Using da Gama' tactic of swinging westward to pick up westerly winds to take him around the Cape of Good Hope, he accidentally hit Brazil which juts eastward into the Atlantic. Since that part of Brazil lay east of the Line of Demarcation, Cabral claimed it for Portugal. He continued to India, but found the same problems da Gama had encountered: Arab hostility and an unwillingness to trade for European goods.

Therefore, the Portuguese decided to change their approach. The third expedition to India, led by da Gama in 1502, took 14 well-armed ships that would take the spice trade by force. The bulky European ships, built to stand the rough Atlantic seas, also provided excellent gun platforms for artillery, and that was the decisive factor in the battle that followed as the Portuguese beat the Arab fleet opposing them. A second decisive victory by the Portuguese fleet in 1509 established the Portuguese reputation for naval invincibility in Eastern waters and started Portugal on the road to establishing a maritime empire in the East.

The architect of the Portuguese Empire in the East was a capable and daring leader, Alphonse de Albuquerque. He realized that such a tiny state as Portugal could not conquer a land empire in Asia and run it all the way from Europe. Therefore, he concentrated on seizing key strategically placed ports that could control the flow of the spice trade. First he captured the strongly fortified island of Goa off the coast of India. From there he could strike out in several directions. Although he failed to cut off Muslim trade coming out of the Red Sea, he did cut off much of the Arab trade by seizing Ormuz at the tip of the Persian Gulf through some masterful bluffing and sailing with only six ships.

The Portuguese maintained their dominance of the East through a combination of astute and ruthless policies. Albuquerque was especially talented in establishing the proper ratio of escort ships to cargo ships. The Portuguese also blackmailed other merchants into paying for certificates of free passage in the Far East. For a few years they managed to have nearly all spices headed for Europe traveling on Portuguese ships.

However, there were serious limits to Portugal's power in the East, which led to the eventual decline of its Empire in Asia. For one thing, the Portuguese, in a fit of religious fervor, had expelled their Jewish bankers and merchants from Portugal, thus eliminating most of Portugal's business community. As a result, the Flemish port of Antwerp handled most of Portugal's spice trade and took much of its profit. Second, Portugal's empire put a tremendous strain on its very limited manpower. Along these same lines, it was very expensive to maintain forts, garrisons, and fleets, especially over such long distances. Finally, the hostility of local rulers, in particular the Mughal Dynasty ruling India, put extra strains on Portugal's ability to hold its empire.

All these factors cut deeply into Portugal's profits and prompted several cost cutting moves. The Portuguese cut corners by not maintaining their ships in the best condition. They would replace lost European crewmen with half-trained natives unfamiliar with European ships and rigging. Finally, because of the limited number of ships and the desire for as large a profit as possible, they would over pack their ships with spices. All these measures led to costly shipwrecks, which cut further into Portuguese profits and caused even more of these cost cutting measures. By 1600, the Portuguese Empire in Asia was in serious decline and increasingly losing ground, first to the Dutch and later to the English.

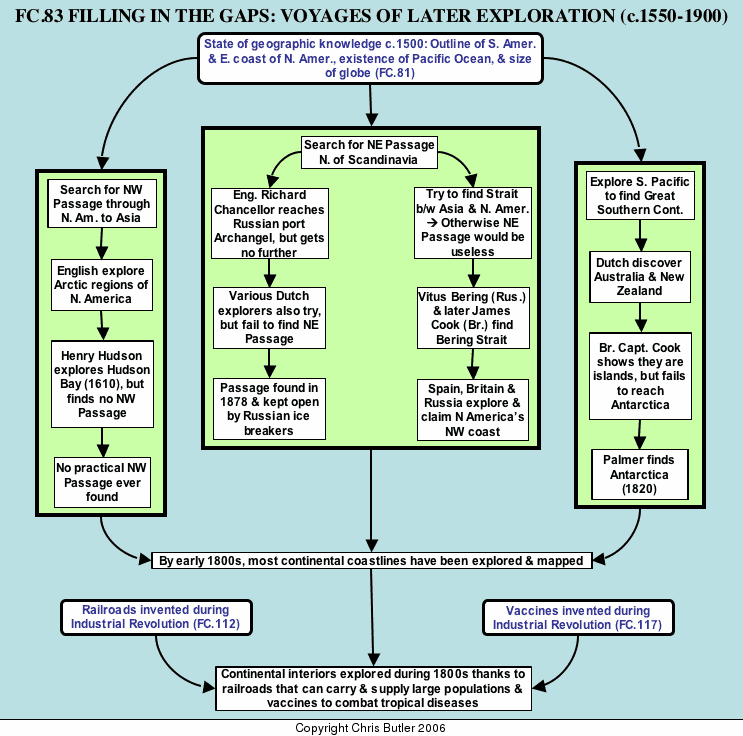

FC83The later voyages of exploration (c.1550-1900)

The progress of the past 150 years still left many questions to answer and myths to dispel concerning the world map. Subsequent explorations concerned four main issues and followed four lines of development:

-

Finding a practical northwest passage around North America to Asia;

-

Finding a practical northeast passage around Scandinavia to Asia;

-

Determining if North America and Asia were connected or separate, which would determine if any north-west or north-east passages, if they existed, could get through to Asia; and

-

Looking for a great southern continent to counterbalance the weight of the Northern Hemisphere.

The English largely led the search for a northwest passage. In 1576, Martin Frobisher, while exploring arctic regions, found an inlet, making him believe he had found the way to Asia and that the Eskimos were Mongols. Further explorations followed. Hopes especially soared in the early 1600's when Henry Hudson found a deep inlet, known ever since as Hudson's Bay. Because of this bay's size and the fact that no one had any idea of North America's size, people believed they had found the way to Asia. However, the North-west Passage was never found, unless one counts voyages by modern nuclear submarines under the Arctic Ocean's icecap.

At the same time, Europeans were trying to find a northeast passage north of Scandinavia to Asia. The English explorer, Richard Chancellor, reached the Russian port of Archangel, but got no further. He did claim to have "discovered" Russia and established relations between it and England. However, it would not be until the early 1700's that the czar Peter I would make Russia an integral part of European affairs. Subsequent attempts by Dutch explorers met with similar failures in finding the North-east Passage. Finally, in 1878, the Swedish explorer, A.E. Nordenskjold, found the Northeast Passage along the rim of the Arctic Ocean and then down the Bering Straits to Asia. Even today, Russian icebreakers ply the route to keep it open for trade and shipping.

The usefulness of the North-east Passage depended on whether North America and Asia are connected. If they were, any northwest or northeast passages would be cut off from entering the Pacific. The answer to this hinged on determining the size of North America, which most people then vastly underestimated. Therefore, a number of expeditions explored the northwest coast of North America to find a passage between it and Asia. The key expedition was led by a Russian, Vitus Bering, who found the passage (the Bering Strait) in 1725. He also claimed Alaska, which Russia held until its sale to the United States in 1867.

For whatever reasons, many people did not believe Bering had found this passage; so more expeditions were launched to this region. Spain and England both explored North America's northwest coast in order to claim lands for the growing fur trade as well as search for the strait of water separating Asia from the New World. Conflicting claims between the two countries were resolved in 1790, with Britain getting everything from Oregon to Alaska. In the meantime, England's most famous explorer, Captain James Cook, confirmed Bering's discovery. By 1800, the coastal map of North America was pretty much in place.

Expeditions in the South Pacific centered on finding the great southern continent. At first, the Dutch led the way in the 1600's in discovering Australia (literally "Southland"), New Zealand (named after a province of the Netherlands), and Tasmania (named after the Dutch captain, Abel Tasman). Since the Dutch had not circumnavigated Australia, many believed it was the great southern continent. In 1768, the English Captain Cook disproved this by circumnavigating it and New Zealand. On his next voyage, he sailed further south to find out if there was a great southern continent, but rough icy waters forced him to turn back. (On his third voyage, which confirmed the existence of the Bering Strait, Cook met his death in Hawaii when trying to recover hostages taken by the natives.) It was not until 1820 that the explorer, Nathaniel Palmer, finally discovered the long sought great southern continent, which we call Antarctica.

Conclusion

By 1800, most continental coastlines had been mapped. The following century was mainly one of exploring and settling continental interiors. Two things helped this process, both of them products of the ongoing Industrial Revolution. First of all, the railroad made possible the movement and supplying of large numbers of settlers in continental interiors. This was especially decisive in the development of the interior of North America. Second, germ theory and the development of vaccines for various tropical diseases meant that Europeans could now explore and conquer tropical regions. This particularly affected Africa, known until then to Europeans as the "Dark Continent" since its interior had been so impenetrable.