Absolute Monarchies in EuropeUnit 14: The rise of absolute monarchies in Eastern and Western Europe (c.1600-1700)

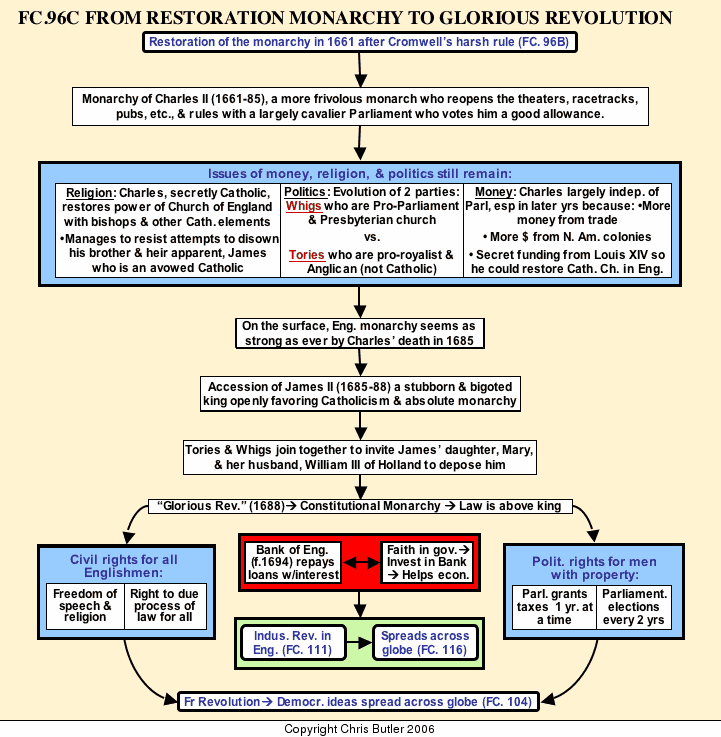

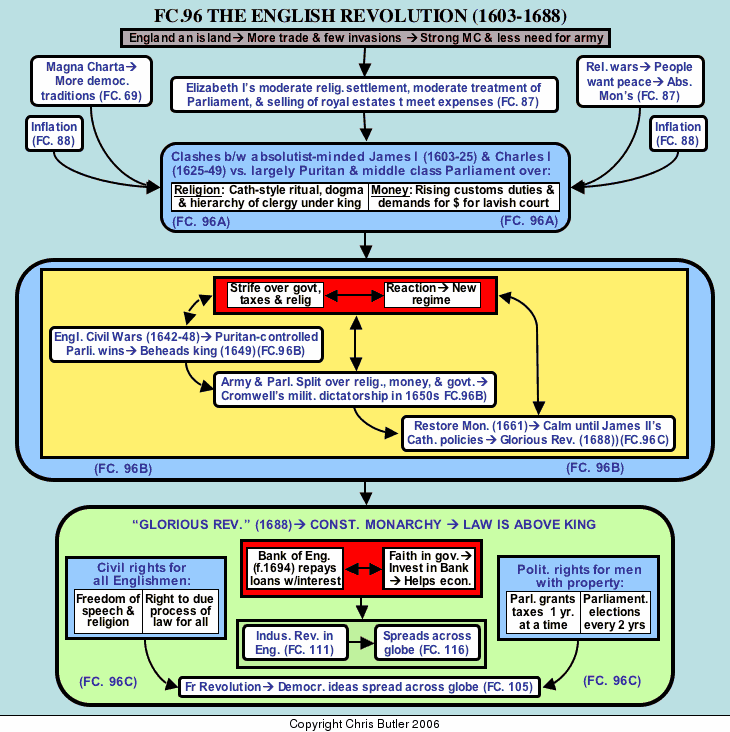

FC96CThe English Revolution From the Restoration Monarchy to the Glorious Revolution (1660-1688)

Charles II and the Restoration Monarchy (1660-85)

The above quoted poem says a great deal about the reign of Charles II. The English people were ready to throw off Cromwell's strict Puritan rule and enjoy life again. Theaters, taverns, and racetracks opened up again. Flamboyant fashions and hairstyles became the rage. And Britain once again became "Merry Old England". Charles, the "Merry Monarch" seemed to be just what the English people needed. However, despite all this, there still remained an undercurrent of tensions in the areas of politics, money, and religion

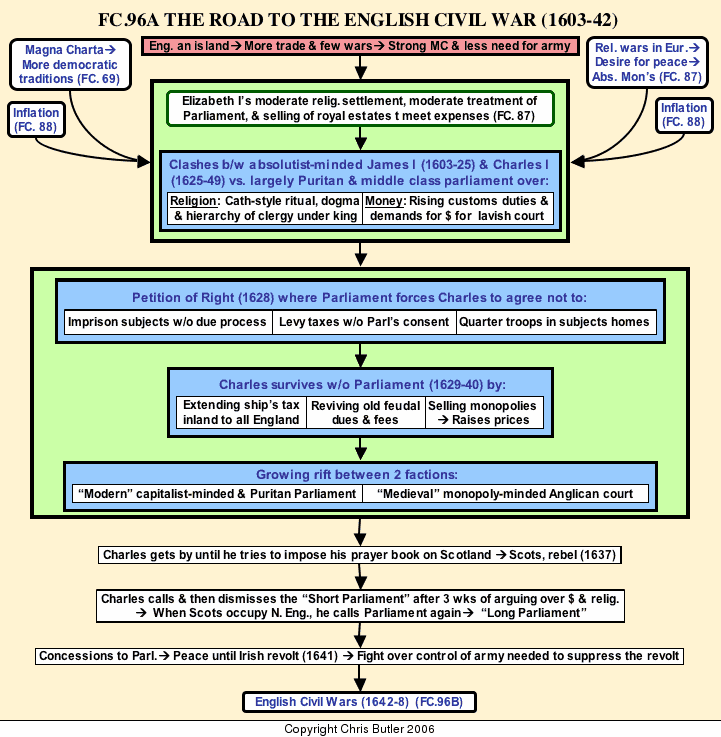

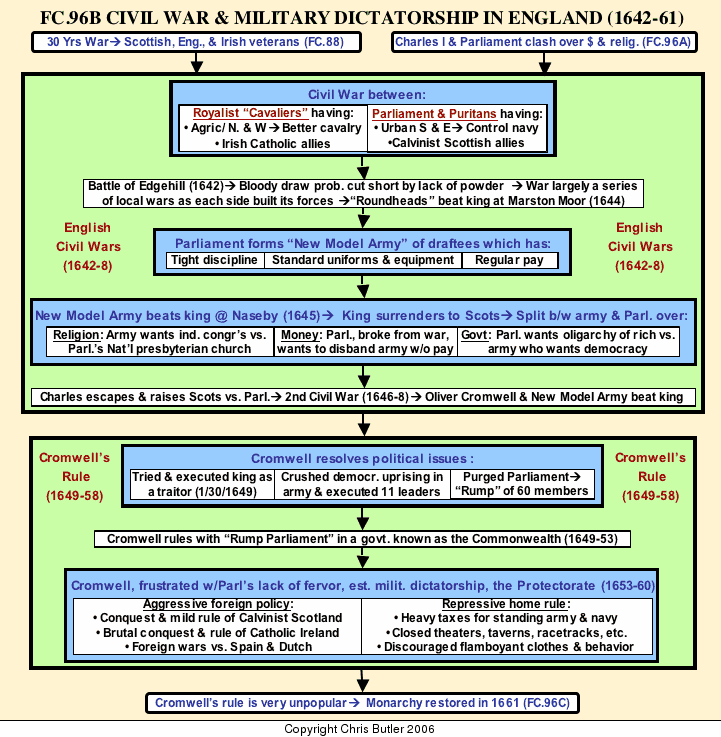

In politics, things seemed much calmer than they had been for decades-- at least at first. King and a largely cavalier Parliament seemed reconciled. Charles was voted a sizable income. The army was paid off, and most of the crown's enemies from the civil war were granted pardons. However, many of the old tensions between king and Parliament still existed. For one thing, the Restoration not only restored the king. It also restored Parliament, which Cromwell had suppressed. In fact, it was the restored Parliament that formally summoned Charles back to England, not the king who summoned Parliament. Parliament itself was divided into two parties: the Tories who favored a strong king and a Church of England largely resembling the Catholic Church, and the Whigs who favored a strong Parliament and more Protestant Church and ritual.

As far as money was concerned, England's wealth was rapidly growing. Cromwell's aggressive foreign policy had intensified England's commercial and naval rivalry with the Dutch, largely due to the Navigation Act, which excluded foreign, and particularly Dutch, ships from carrying English goods. This led to three short but bitterly fought naval wars with the Dutch (one under Cromwell and two under Charles II). Although the Dutch held their own, the expense and stress of their wars against England and France allowed the English to replace them as the premier naval and commercial power in Europe by 1700. Between 1670 and 1700, England's foreign trade grew by 50 per cent, and the king's customs revenues tripled. Despite this new prosperity, Charles' allowance from Parliament still could not satisfy his extravagant personal tastes and style of living. Instead of letting this lead to a clash with Parliament, as had led to Civil War in 1642, Charles neatly sidestepped Parliament by signing the Secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV. This gave Charles a handsome pension in return for the promise to turn England Catholic when the time was ripe.

Concerning religion Charles II was sly enough to keep to himself his beliefs in the Divine Right of Kings and the Catholic faith. Although he did not openly profess his Catholic faith until he was on his deathbed, he did restore lands confiscated since the civil war to the Church, crown, and nobles. He also restored the power of the Church of England, re-establishing the church courts and persecuting anyone, especially Puritans, not conforming to the Church's doctrines.

Much more unsettling was the fact that Charles had many children, but none of them were legitimate. That left James, Charles' brother and an avowed Catholic, next in line for the throne. This alarmed the Puritans, who put pressure on Charles to disinherit his brother. Puritan pressure intensified with Titus Oates' "Popish plot," a preposterous rumor that the Jesuits were plotting to kill Charles and massacre all the Protestants in England. This led to two years of anti-Catholic persecutions and hysteria, which put Charles in an awkward position, since he did not want to be exposed as a "papist" himself. Rumors of his funds from France made his position that much more delicate. In the end, the slippery Charles managed to avoid disinheriting his brother. He even ruled without Parliament the last few years of his reign, getting by on his subsidies from Louis XIV. By Charles' death in 1685, it seemed the king was as strong as ever.

James II and the Glorious Revolution (1685-88)

As strong as the new king, James II, may have appeared, there was no way he could undo the changes of the last 80 years. Charles II was a capable monarch quite adept at handling the Whigs. Unfortunately, James had nearly all the qualities to ensure getting himself dethroned, being bigoted, stubborn, and quite inept. His worst mistake was his open preference for Catholicism. He suspended laws keeping Catholics out of public office and even recruited Irish Catholics for his army. When his own bishops tried to advise him to reconsider his openly favoring Catholicism, he jailed seven of them in the Tower of London.

Even the Tories came to fear the king's religious views more than they did the Whigs' political views. Finally, they joined with the Whigs in inviting James' Protestant daughter, Mary, and her husband, William the Prince of Orange, to come from Holland and dethrone James. What followed has been known ever since as the Glorious Revolution, partly for being virtually bloodless (except for James' nosebleed), but mainly for what it accomplished. William and Mary's Dutch army landed unopposed and marched to London. James' army deserted him, and he fled to France.

Royalty and Parliament then came to an agreement whereby William could use England's resources to help stop Louis XIV's drive to dominate Europe. In return, William and Mary guaranteed Parliament's rightful place in the government and signed the Bill of Rights, precursor to our own Bill of Rights. This assured Englishmen such liberties as free speech, free elections, no imprisonment without due process of law, and no levying of taxes without Parliament's consent. In addition, the king agreed to call for new elections every three years. The king could still formulate policy and name his officials. However, the balance of power had definitely shifted in favor of Parliament, especially since it controlled the purse strings. Money was only granted one year at a time, which meant that the king would have to call Parliament each year just to have the cash needed for his policies. This new government where even the king where was subject to the law and certain legal procedures in ruling is called constitutional monarchy,

In the years to come, Parliament gradually gained more power at the expense of the kings. This process gained momentum when the German prince, George of Hanover, became king in 1714. His main interests remained on the continent, and he was generally content to let his allies, the Whigs, run the government for him.

Results of the English Revolution

The struggle between kings and Parliament throughout the 1600's ended in a clear-cut victory for Parliament. While a more democratic government emerged as a result of the English Revolution, keep in mind that rather high property qualifications still kept the vast majority of Englishmen from voting.

However, the English Revolution would benefit all England in two areas: civil rights and the economy. For one thing all Englishmen did gain certain civil rights, such as free speech and the right to a fair trial by a jury of peers. Also, all Christians except gained religious freedom, except Catholics and Unitarians, who eventually, would also be tolerated. The English Revolution also opened the way for more democratic reforms over the next two centuries, until England would became a truly democratic society. The power and success of these principles would spread to the American and French Revolutions, and from France to the rest of Europe and the world.

Economically, the English revolution saw the triumph of capitalism in England. One important aspect of this was Parliament's founding of the Bank of England (1694) through which the government did much of its business. The important thing here was that the government guaranteed repayment with interest on any loans it took out. This contrasted sharply with the old medieval method whereby kings took out personal loans, often did not bother to pay them back, and let the liability for the loans go to the grave with them. Now that government was identified more with Parliament, liability for the loans did not die with the king. Therefore, people were more willing to loan the government money, since they knew they would get it back with interest.

Since the government was largely run by hard-nosed middle class businessmen rather than extravagant nobles with no sense of the value of money, it would use these loans wisely by investing them in business and new industries. That, in turn would improve the economy, which not only could pay more taxes, but also invest further in the Bank of England, which could invest even more money in economic development, and so on. Therefore, England, along with the Dutch Republic, was one of the first modern states to operate at a profit rather than in chronic debt. And, as a result, England would be the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in the 1700's, a factor that would make Europe the dominant culture on the globe by 1900.

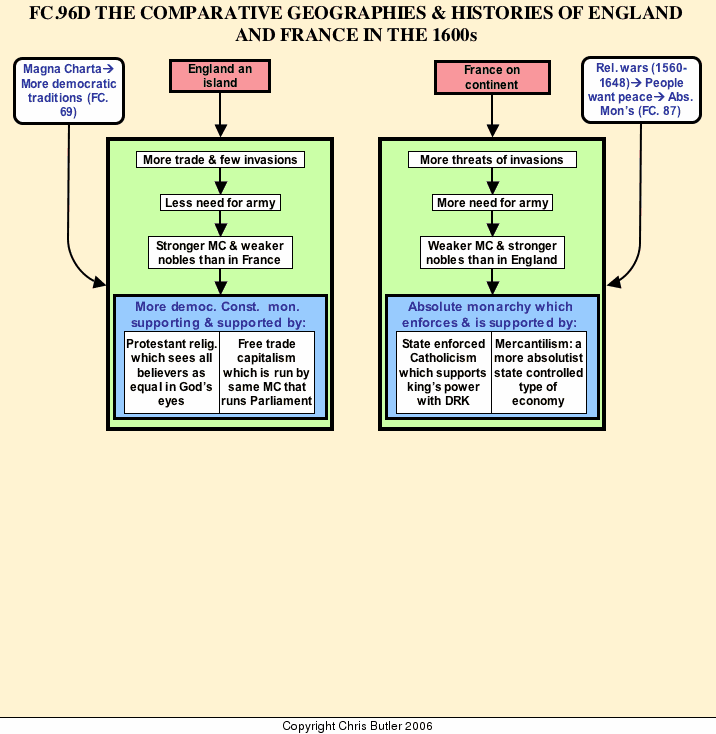

FC96DA Comparison of English & French Histories in the 1600S

Another factor affecting England has been a longer democratic, or more properly quasi-democratic, tradition compared to that of France, going back at least to the Magna Charta in 1215, although that was drawing upon an earlier charter signed by Henry I around 1100, which itself drew upon older traditions of Saxon liberties. Together, England’s protected position, but still very close to the continent, and its quasi-democratic roots blessed it with few invasions and more trade. Therefore it had less need for a strong army, giving it a stronger and richer middle class and a less powerful and distinct nobility than in France. For example, lower nobles and the upper middle class sat together in the House of Commons as a group known collectively as the gentry. While titles of nobility could not be bought in England, neither could they be lost, as in France, for the stigma of working to support oneself like the a commoner.

By 1700, England had worked out a constitutional monarchy that was more democratic, giving all freemen certain civil rights, although withholding the vote from all but about 5% of the men. Two major pillars supported this new order. One was Protestantism, which sees all believers as (at least spiritually) equal in God’s eyes. In the early 1600s when one could not separate religion and politics, spiritual equality led the way to political and social equality. The other pillar was free trade capitalism, versus the quasi-socialistic system of medieval guilds, royal monopolies, and mercantilism. Running this was the same Protestant middle class gentry that ran Parliament and claimed that God values all jobs equally. In the 1700s the combined dynamics of middle class capitalism and democracy would vault England into global leadership in terms of finance, naval and colonial power, and eventually industrialization.

France’s geography and history took it down a somewhat different path, at least until the 1800s. Its position on the continent presented more threats of invasion, as well as opportunities for conquest. Either way, it had a greater need for an army, which is expensive and disruptive to trade when it is actually used in wars. Therefore, the middle class had less clout and status in France than its counterpart in England, as witnessed by the more prominent role played by Parliament in English history than that played by its French counterpart, the Estates General. Also, there was no blending of the upper middle class and lower nobles corresponding to the gentry in England.

As a result, France experienced an absolute monarchy that was supported by its religious and economic systems. One was state enforced Catholicism with the doctrine of Divine Right of Kings, which supported the principle of absolute monarchy. The economic counterpart to absolute monarchy was mercantilism, which did recognize the importance of nourishing a strong national economy, but did it in an overbearing absolutist manner that stifled initiative and may have done as much harm as good.

However, instead of continuing on diverging paths, France would follow with its own democratic revolution and the triumph of free trade capitalism for two major reasons. One was political and economic competition from Britain that France had to adapt to in order to survive. The other was a common cultural and historical heritage going back to ancient Rome, which made France and England much more alike than either of them might want to admit.

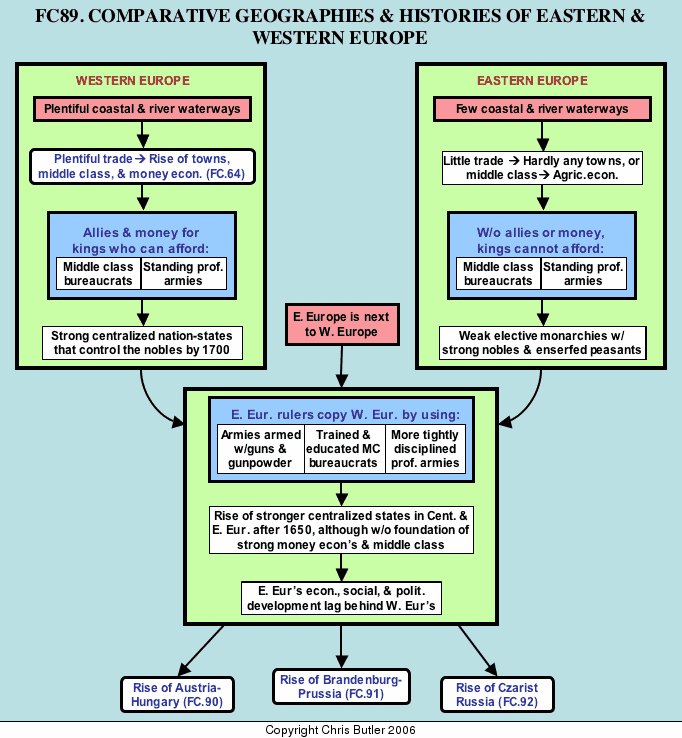

FC89The Comparative Geographies and Histories of Eastern and Western Europe

Between East and West

Throughout the modern era, there have been striking contrasts between the histories, economies, and politics of Eastern and Western Europe. After World War II, those differences became especially obvious with the Soviet led Warsaw Pact forces poised on one side of the Elbe River and the Western NATO alliance on the other. As so often in history, the underlying basis for these differences has been geography.

First of all, Europe's latitude lies quite far north. For example, Rome, Italy is about as far north as Chicago, Illinois. However, it has a much warmer climate, especially in the winter. This is because Western Europe gets the moderating effects of a warm current known as the South Atlantic Drift and warm sea breezes coming across the Mediterranean from North Africa. Eastern Europe is too far inland to benefit much from either of these effects, and thus has more extremes in climate, especially in the winter.

However, the critical difference between Eastern and Western Europe has to do with waterways. Western Europe has an abundance of navigable rivers, coastlines, and harbors along the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean, North, and Baltic Seas. In the High Middle Ages, these fostered the revival of trade and the rise of towns, a money economy, and a middle class opposed to the feudal structure dominated by the nobles and Church.

Kings also opposed the nobles and the Church, so the middle class townsmen provided them with valuable allies and money. With this money, kings could buy two things. First of all, they could raise mercenary armies armed with guns to limit the power of the nobles. Secondly, they could form professional bureaucracies staffed largely by their middle class allies who were both more efficient since they were literate and more loyal since they were the king's natural allies and dependant on him for their positions. As a result, kings in Western Europe were able to build strong centralized nation-states by the 1600's.

Eastern Europe, in stark contrast to Western Europe, provided practically a mirror image of its historical development before 1600. Being further inland compared to Western Europe hurt Eastern Europe's trade, since the sea and river waterways vital to trade did not exist there in such abundance as they did in Western Europe.

Factors limiting trade also limited the growth of a strong middle class in Eastern Europe. This meant that kings had little in the way of money or allies to help them against the nobles. That in turn meant that peasants had few towns where they could escape the oppression of the nobles. Therefore, strong nobilities plus weak, and oftentimes elective, monarchies were the rule in Eastern Europe before 1600. At the same time, the nobles ruled over peasants whose status actually was sliding deeper into serfdom rather than emerging from it.

However, there was one geographic factor that favored Eastern Europe's rulers after 1600. That was the fact that Eastern Europe is next to Western Europe. As a result, some influence from the West was able to filter in to the East. In particular, Eastern European rulers would emulate their Western counterparts by adopting firearms, mercenary armies, and professional bureaucracies. As a result, they were able to build strongly centralized states in the 1600's and 1700's. This was especially true in three states: Austria-Hungary (the Hapsburg Empire), Brandenburg-Prussia in Germany, and Russia.

However, the lower incidence of towns and a strong middle class has continued to hamper the development of Eastern European states in the modern era, since rulers there have had to build their states with less of the strong foundation of a money based economy, basing their states on less developed agricultural economies. While the strong middle class in Western Europe would provide the impetus for further developments in the West, notably the emergence of democracy and the Industrial Revolution, these two things have had a harder time taking root in Eastern Europe, making its overall political and economic development more difficult.

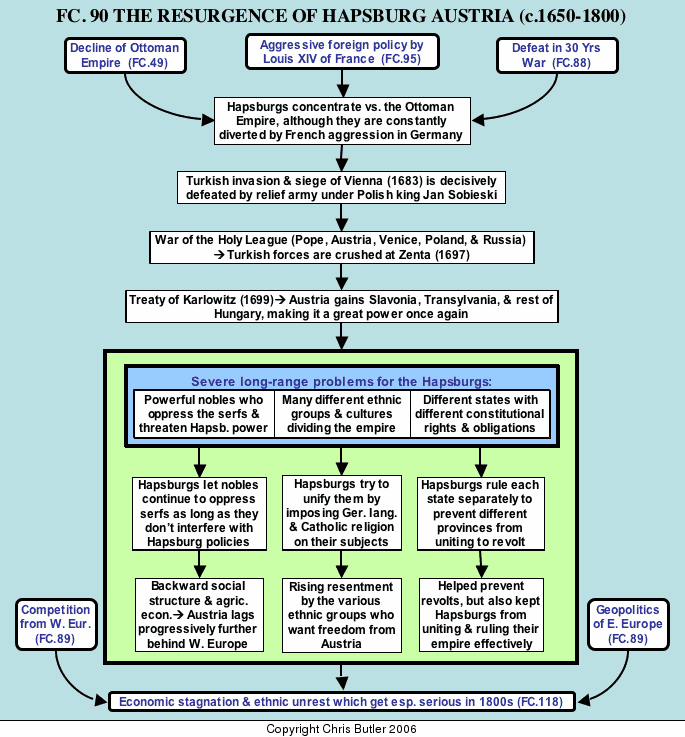

FC90Hapsburg Austria Resurgent (c.1650-1700)

We came, we saw, God conquered.— Jan Sobieski, announcing the relief of the siege of Vienna from the Ottoman Turks in 1683

When the Thirty Years War and Peace of Westphalia stifled Austrian ambitions in Germany, the Hapsburgs expanded eastward against the Ottoman Empire. Ever since the death of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1565, the Ottoman Empire had been in serious decline, with a corrupt government, rebellious army, obsolete military technology, and decaying economy. Such a faltering empire was a tempting target for its neighbors. However, the Hapsburgs were never able to concentrate solely on the Turks. This was because France under Louis XIV posed a constant threat of invasion to the various German states, which forced the Hapsburgs to divide their attention between east and west.

The Hapsburg ruler at this time was Leopold I (1657-1705), a mediocre ruler, but lucky enough to have capable generals to lead his armies. Leopold's main goal was control of Hungary, which had been divided between Turkish and Austrian rule for over a century. When Leopold supported rebels in Transylvania against the Turks, war and an Ottoman invasion resulted. At this time, the Turks were ruled by an able family of viziers, the Koprulus, who started reforming the state in order to make the Ottomans a power to contend with once again. As a result, when the Turkish army started to advance westward, the alarm went up all over Europe, with even Louis XIV sending 4000 troops to help the Hapsburgs (and make himself look like a good Christian). In 1664, a much smaller, but better equipped and trained allied army caught and destroyed a Turkish army while it was crossing the Raba River. This was the first major victory of a Christian army over the Ottomans. However, it encouraged Leopold's allies to feel secure enough to take their troops home, leaving him to face the Turks alone. Instead of continuing the fight, he signed a humiliating peace that damaged his reputation considerably. As a result, the Hungarian nobles under his rule rebelled and called in the Turks to help them.

This triggered the Turks' last major invasion of Europe, climaxing at the siege of Vienna in 1683. A huge Turkish army of possibly 150,000 men, but with no large siege artillery, was faced by only the stout walls of Vienna and a garrison of ll,000 men. The siege lasted two months as the Turks gradually used the old medieval technique of undermining the walls. Just as the hour of their victory approached, a relief army from various European states arrived and crushed the Turkish army. From 1683 to 1700, Hapsburg forces and their allies advanced steadily against the Turks, only being interrupted by having to meet French aggression in the West. In 1697, the allied forces demolished another Turkish army at Zenta and watched as the once proud Janissaries murdered their own officers in the rout. The resulting treaty of Karlowitz (1699) gave Austria all of Hungary, Transylvania, and Slavonia. Karlowitz re-established Austria, now also known as Austria-Hungary, as a major European power. From 1700 until the end of World War I in 19l8, the Hapsburg Empire would dominate southeastern Europe, while the Ottoman Empire staggered on as the "Sick Man of Europe."

Although the Hapsburg Empire had regained its status as a military and diplomatic power, it still had serious internal problems, namely a powerful nobility ruling over enserfed peasants, a hodge-podge of peoples with nothing in common except that they all called Leopold their emperor, and a variety of states that each had their own rights, privileges and governmental institutions. The Hapsburgs dealt with these problems in three ways. First of all, they neutralized the nobles politically by making a deal that let them continue to oppress the peasants as long as they did not interfere in the government. This left the nobles fairly happy while giving the Hapsburgs a free hand to run the state, largely with soldiers and bureaucrats recruited from other parts of Europe. Unfortunately, this also left the empire socially and economically backward. Second, they tried to unite their empire religiously and culturally by imposing the Catholic faith and promoting the German language throughout their empire. Trying to submerge native cultures, such as that of Bohemia, under Catholicism and German culture mostly caused resentment against Hapsburg rule. Finally, they ruled each principality (Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, etc.) separately with its own customs and institutions. This kept nobles of different provinces from being able to combine in revolts against the Hapsburgs, but it also left the empire fragmented into a number of separate provinces. A large standing army and bureaucracy also held the empire together.

For the next two centuries the Hapsburg Empire would be a major power in Europe. However, it had a number of serious problems that it never adequately solved, being socially and economically backward and fragmented into a large number of provinces and increasingly restless ethnic groups. Together, these problems gradually ate away like a cancer at the Hapsburg Empire, rotting it out from within until there was hardly anything left to hold it together by the twentieth century.

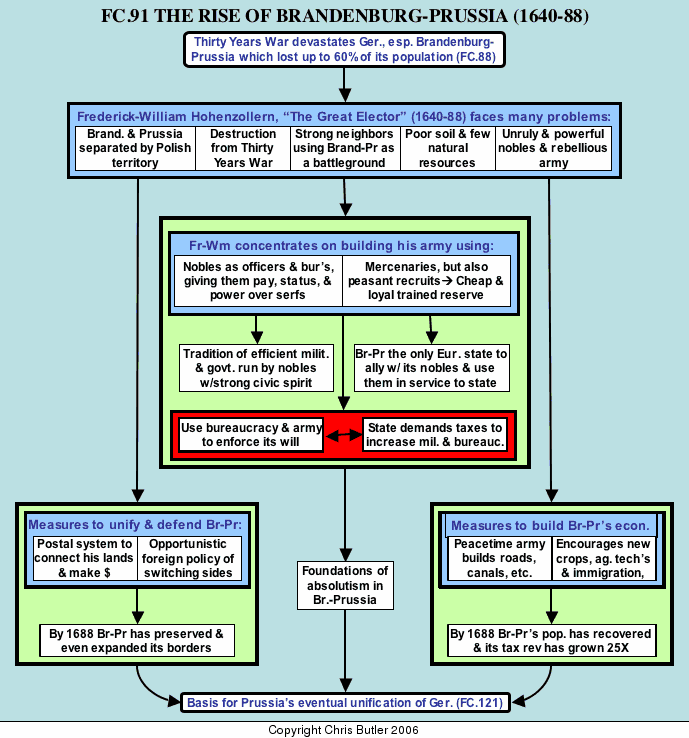

FC91Brandenburg-Prussia & the Roots of Modern Germany (1640-88)

Brandenburg had lived under the rule of the Hohenzollern dynasty since l4ll when Frederick of Hohenzollern had purchased the territory and one of the seven electoral votes of the empire along with it. In l6l8, the elector, as the ruler of Brandenburg was known, also got control of Prussia some l00 miles to the east, holding it as a vassal of the king of Poland. Brandenburg especially suffered during the Thirty Years War, since it was caught between the Catholic imperialists to the south and Swedes to the north, not to mention its own rapacious mercenaries. This was the situation when Frederick William, known as the Great Elector, took power in 1640.

Frederick William found an imposing array of problems that fell into three basic categories: geographic, military/diplomatic, and economic. Frederick William's main geographic problem was that the territories of Brandenburg and Prussia were separated by l00 miles of Polish territory, making it very difficult to control and administer. Economically, Brandenburg was a poor country with few resources and a sandy soil that earned it the nickname "the sandbox of Germany". There were several factors aggravating the military and diplomatic situation. Worst of all was the devastation suffered at the hands of the Imperialists, Swedes, and Brandenburg's own troops. An estimated 60% of population was lost from the war, falling from l.5 million to 0.6 million. Not only that, but Swedish troops were still on Brandenburg's soil in l640, with other powerful threatening neighbors, such as Poland to the east and France to the west. To meet these threats, Frederick William's army consisted mainly of unruly mercenaries as likely to plunder his lands as defend them. And he also faced a powerful class of nobles known as junkers who were a constant obstruction to the government.

Frederick William figured that, above all else, he needed to tackle his military and diplomatic problems by building a good army to protect himself and his realm. The first step was to use what few reliable troops he had in order to destroy his old army of worthless mercenaries. One by one, he eliminated his old regiments until he had only an army of 2500 men, but it was a loyal core upon which to build. Through diligence and hard work, Frederick William built an excellent army of some 8000 men by l648. This was enough to give him a voice in the treaty talks at Westphalia. His main goal was to get Pomerania which, although legally Brandenburg's, was occupied by Swedish troops. He had to settle for half of Pomerania, but that was more than he could have expected eight years earlier, and it did give him a coastline on the Baltic Sea.

Inspired by his success, Frederick William kept building up his army and bureaucracy. For an officer corps and civil officials, he turned to the junkers. Like his contemporary, Leopold I of Austria, he let the nobles maintain their dominance over the serfs. But unlike Leopold, who did this to keep the nobles out of the government, Frederick William expected service to the state in return for those privileges. The junkers were expected to serve in the army as officers or as a highly efficient civil service that could provide better support for the army in the way of tax collection and supplies. They received fancy uniforms and excellent training, and soon had developed a high morale and pride in themselves as the officer class of Brandenburg-Prussia. That tradition of a proud Prussian officer class as the backbone of the state would continue all the way down to the twentieth century. As a result of this policy, Brandenburg-Prussia was the only state in Europe where the government successfully allied with the nobles and used them effectively in government service.

For recruits, Frederick William and his successors started to rely increasingly on peasant draftees rather than on undependable and expensive foreign mercenaries. Such soldiers were much cheaper than mercenaries and much less prone to looting, although not as efficient,. During peacetime, they could be kept in training for a few months each year while letting them farm and be productive the rest of the time. By the end of his reign, Frederick William was able to field an army of 45,000 men, with a smaller, but still sizable standing peacetime army.

In addition to defense, the army also helped Frederick William increase his power internally, since he could use it to demand taxes and enforce his policies. With those taxes, he could increase his army, which further increased his authority, and so on. As a result, Frederick William laid the firm foundations for absolutism in Brandenburg-Prussia.

As far as Brandenburg-Prussia's divided geography was concerned, Frederick William developed a postal system, which better tied together his scattered realm and also generated more revenue for the government. Even so, Brandenburg-Prussia was still a small fish in a big pond, and a turbulent pond at that. The later l600's were hardly more peaceful than the early l600's, with an aggressive Sweden to the north and Louis XIV's France to the west keeping Europe's armies constantly on the march. Thus, Brandenburg-Prussia's geography and revived army both forced and allowed Frederick William to pursue a foreign policy that was, in a word, opportunistic.

Throughout his reign he skillfully switched sides whenever convenient and sold his army's services to the highest bidder or most useful allies. For example, in the fighting between Louis XIV and the Dutch Republic, he switched sides three times. And in the Northern War between Poland and Sweden (l655-60), Frederick William at first was neutral, then on Sweden's side, and finally on Poland's side in return for recognition of his title to Prussia being totally independent of his overlord, Poland. This independent title gave Frederick William special status among German princes, who were still in theory under the power of the Holy Roman Emperor. In fairness to Frederick-William, it should be said that switching sides so often was typical of European diplomacy at this time. Although Frederick William's policies gained him some land and the independent title to Prussia, his major accomplishment was holding his original realm together in the midst of such powerful neighbors while rebuilding its prosperity.

At the same time, Frederick William was every bit as talented a ruler in building his realm economically as he was in military and diplomatic affairs. There were several things he did to restore Brandenburg-Prussia's prosperity. For one thing, he took an active interest in the development and use of new agricultural strains and techniques that would allow crops to thrive in Brandenburg's sandy soils. Considering the fact that the vast majority of the populace then was still concerned with agriculture, this was especially significant. Also, Frederick William encouraged immigration to repopulate his realm. Louis XIV's revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 (which took religious freedom from the French Huguenots) certainly helped Frederick William here, since some 20,000 Huguenots found their way to new homes in Brandenburg-Prussia. This was largely with the help of the Great Elector, who supplied the Huguenots with traveling money, guides, land, tax exemption for six years, and various other privileges. Thus, France's loss was Brandenburg-Prussia's gain, since the Huguenots were some of the hardest working and most highly skilled people in Europe. Finally, the government controlled monopolies on the production and sale of such commodities as salt and silk. The efficient management of these monopolies raised important funds for the government.

Frederick William's military reforms and concern for the economy caused him to use the army during peacetime to develop public works projects. For example, the army built a canal connecting Berlin, the capital, to the Oder River, thus increasing trade and tax revenues. Much of that extra revenue surely went back into the army. But at least it was partially able to pay for itself in peacetime. This also kept the army from causing trouble during times of peace and idleness.

By Frederick-William's death in l688, Brandenburg-Prussia was in better shape than before the Thirty Years War. Its population was back up to pre-war levels, while its tax revenues had increased from 59,000 thalers in the l640's to l,533,000 thalers in l689, over twenty-five times its original revenue. Its army provided more security than ever before while also giving Brandenburg-Prussia an unprecedented amount of international prestige and respect. However, this was only the beginning. Frederick William's reforms set the stage for two centuries of steady growth and expansion that would culminate in the unification of Germany and its rise to the status of a world power in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

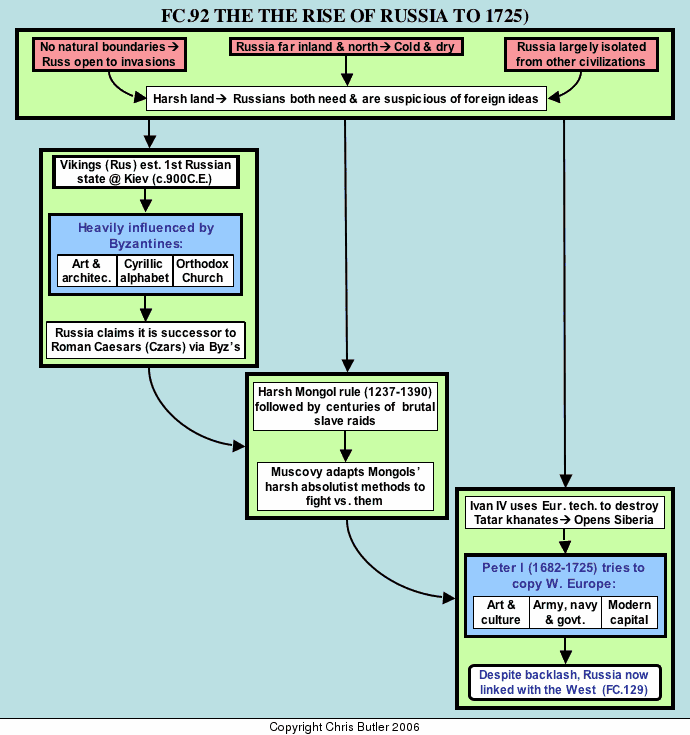

FC92The Geography and Patterns of Russian History

The last and easternmost state to assume a place in European culture and diplomacy was Russia. Three aspects of Russia.s geography have had a major impact on its history. First of all, its location on a high northern latitude and far inland gave it a cold and dry climate. That, combined with large areas of poor or mediocre soils, made it a cold dry steppe in which it is difficult to survive, let alone prosper. Famine has affected Russia on an average of one year out of three throughout its history.

Second, Russia lies on the vast Eurasian Steppe with no formidable natural barriers, which has invited a number of invasions with tragic results. In its early history, the main threat would come from the nomadic tribes to the east, making Russia a battleground between nomads and farmers. Only more recently have Russia’s neighbors to the west been a serious threat, as seen by the loss of an estimated 27,000,000 people in World War II. Ironically, Russia’s harsh climate has saved it from invasion more than once. Napoleon and Hitler both found out the power of “General Winter” when they made the mistake of trying to conquer this vast northern giant.

Finally, Russia’s inland location to the north and east of Europe has left it largely isolated from the mainstream of developments in Europe. Altogether, Russia’s geographic features have made it a harsh land facing constant invasions. As a result, Russians have historically been torn between needing and wanting foreign ideas with which they could better compete and survive on the one hand and a suspicion of foreigners bred by the continual threat of invasions they have faced on the other.

This love-hate relationship with foreign ideas has created recurring stress throughout Russian history all the way to the present. In its early history, one can see four major stages of development where it has taken place. The first of these was when the first Russian state, centered on Kiev, was confronted with Byzantine influence from the south. The Cyrillic alphabet, Russian Orthodox Christianity, and Russian art and architecture all bear the distinctive marks of Byzantium. The next major influence came from the Mongols who conquered Russia in the 1200’s and introduced the harsh absolutist strain that became a hallmark of later Russian government. The last two phases, the reigns of Ivan IV and Peter I, witnessed growing influence from Western Europe. Ivan IV’s reign saw the first attempts to gain access to the West for its technology, the use of Western artillery in the conquest of two Mongol khanates, and the attempts to replace the traditional Russian nobility with a new nobility of service. While his efforts had only limited success, they helped set the stage for the more widespread and concerted efforts of Peter I to westernize Russia. Despite the conservative backlash that followed Peter’s reign, Russia from that time on was an integral part of Europe and European civilization.

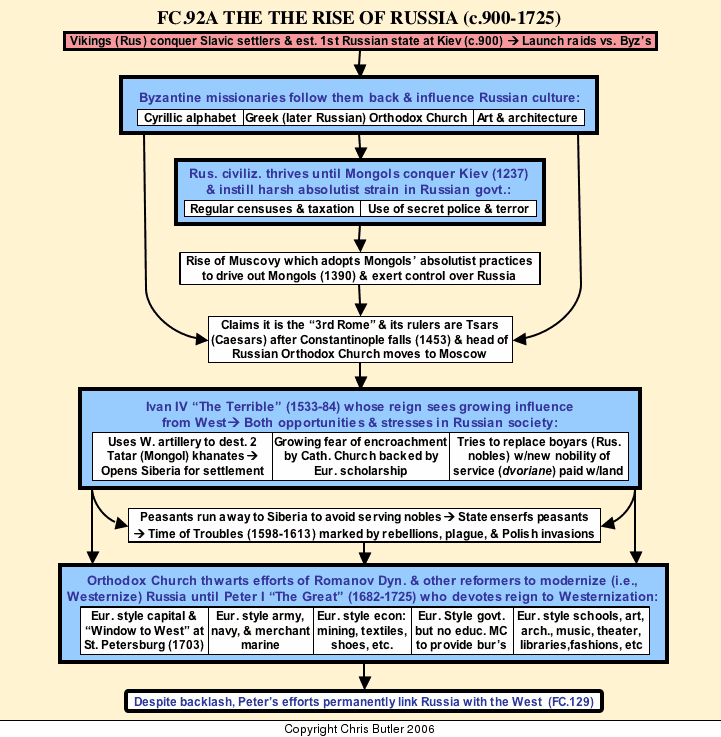

FC92AThe Early History of Russia to 1725

Early history

The earliest written references to inhabitants in Russia were the Scythians, nomadic horsemen who inhabited the southern steppes in the time of the classical Greeks. Russia’s grassy plains provided ideal grazing for these nomads’ sheep and horses. Some time after 500 A.D., various Slavic tribes, ancestors of most of today’s Russians, moved in and settled down in Russia. Then, around 900 A.D., Vikings, known as the Rus, came in and united the Slavs under a state centered around Kiev.

The Rus used Kiev and other Russian cities as bases from which to raid their more civilized neighbors to the south, in particular the Byzantines. The first such raids were successful in forcing tribute from the emperors in Constantinople in order to make the Rus go home. Later raids were met by the dreaded Greek fire, which set the Rus’ navy and the very sea itself ablaze. In the wake of Greek fire came Byzantine missionaries, who converted the Rus and their Slavic subjects to Greek Orthodox Christianity. Byzantine civilization has had a profound impact on Russian culture. Many Russians today still cling to the Orthodox faith in spite of over seventy years of Communist disapproval. The Cyrillic alphabet and the onion domes that grace the tops of the Kremlin also bear solid testimony of Byzantine influence on Russia to this day.

Russian civilization and the Kievan state flourished until l223, when the most devastating wave of nomadic invaders in history arrived: the Mongols. In 1223 C.E. at the Kalka River, the Russian princes were overwhelmed by a small Mongol army whose numbers were exaggerated by panic and confusion to some l50,000 men. Europe itself was only spared Asia’s fate by luck rather than the prowess of its armies. Upon Chinghis Khan’s death his far-flung hordes returned to the Mongol homeland to elect a new khan. However, the Mongols returned to Russia in l237 to finish its conquest. They even struck into Poland and Hungary, giving Europe a taste of things to come. Amazingly, fate intervened again when Chinghis Khan’s successor died. Thus Europe was spared a second time, and the incredible energy that had sent the Mongols to the corners of the known world started to fizzle out. However, Russia remained the western frontier of Mongol power.

Mongol rule was exercised indirectly through whichever Russian princes were most willing and able to carry out the will of their masters. This meant doing things in the rough and brutal Mongol way, so that after two centuries of Mongol rule, much of the Mongol character and way of running a state rubbed off on their Russian vassals. The Mongols’ expectation of blind obedience to authority and the use of such things as a secret police to enforce their will and inspire terror, a postal relay rider system for better communications, and regular censuses and taxation became a major part of the Russian state that would later evolve.

Muscovy

The most successful of the Russian vassals to adapt Mongol ruling methods were the princes of Muscovy (Moscow) who earned the sole right to collect taxes and dispense justice for the Mongols, while increasingly resembling their Mongol masters in their ruling and military techniques. Eventually, the Muscovite princes turned against their Mongol masters and ended their rule in l390. It was around Moscow that the modern state of Russia would form.

Mongol rule was gone, but the Mongol terror was not. Nearly every year, the horsemen of various neighboring khanates would ride in to spread a wide swathe of death and destruction, taking thousands of Russian prisoners to the slave markets back home. These raids would depopulate whole regions of Russia, even Moscow itself being sacked by the Mongols five different times between l390 and l57l. While destabilizing Russian society, these raids also forced the Muscovite princes to tighten their grip on society in order to provide better defense. Muscovite absolutism grew even stronger when the metropolitan, or patriarch, of the Russian Orthodox Church moved to Moscow, giving it claim to the title of “the third Rome” after Constantinople and Rome itself. Likewise, Muscovite rulers laid similar claim to the title of Czars (Caesars).

The first truly memorable Czar was Ivan IV, known as “the Terrible” (l533-84). Ivan’s reign saw four momentous developments, all of which can be seen as growing efforts to bring in influence from Western Europe. The first, the destruction of the neighboring khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan to the south and east, was made possible by the use of European artillery. Although the Mongols of the Crimea still remained to carry out their depredations, destroying these other two khanates did relieve the Russian people of some suffering from nomadic raids. It also opened the way for the rapid expansion of the Russians eastward across Siberia to the Pacific in much the same way the United States would spread rapidly westward to the same ocean in the l800’s.

Second was Ivan’s long but unsuccessful war against Poland and Sweden to conquer Livonia and gain closer access to Western Europe. Compounding this failure was the third development, the Orthodox Church’s growing fear of the Roman Catholic Church. Causing this was increased missionary activity by the Jesuits in the Ukraine and eastern Baltic. Using Western scholarship in debates with the less educated Orthodox clergy, they were able to convert growing numbers of people in these regions. Naturally, the Orthodox clergy saw this as an especially serious threat to their religion and became the most ardent opponents of contact with the West.

Finally there was Ivan’s fight against the boyars, the powerful Russian nobles. Blaming them for the death of his beloved wife, he launched a concerted campaign against them by setting up the Oprichnina, or state within a state, where Muscovy was split between the traditional state and his own Oprichnina. Ivan then launched an eight-year reign of terror (l564-72) against anyone he suspected of disloyalty. He also tried to replace the boyars with a new nobility of service that would be more subservient to the crown. Since Russia’s economy was still quite backward, the czar had to pay this service nobility with land worked by peasants. Consequently, many peasants fled to the freer lands in Siberia, now opened for settlement by Ivan’s wars. The government reacted with a series of laws that tied the free peasants to the soil and made them serfs.

The “Time of Troubles”

Ivan’s reforms and purges made his reign a turbulent and costly one. Also, Ivan’s accidental slaying of his most able son in a fit of passion left the throne to the feebleminded Feodor, who liked to spend most of his time praying and ringing church bells. The reins of government thus fell to the boyar, Boris Gudonov, who succeeded Feodor as Czar in l598. At this point, everything in Russia seemed to go wrong at once. The Boyars resisted his attempts to increase royal power. The Orthodox Church thwarted Boris’ early attempts to bring Western European knowledge and culture to Russia. And, worst of all, in l601 a horrible drought and famine killed millions of peasants who revolted out of desperation and the belief that the famine was the Czar’s fault. The rebels got help from the Poles, who supported a supposed son of Ivan IV as Czar. Boris successfully defended his realm until, right on the verge of victory, he suddenly died, capping off a remarkably unlucky reign. The Poles had little better luck in holding the throne, their candidate being assassinated and replaced by another boyar. More peasant revolts and another Polish invasion, which took Moscow, tore Russia further apart. Finally, the Church managed to rally the people, drive out the Poles, and set up a stable government. A national assembly called the Zemsky Sobor set up a new dynasty, the Romanovs. However, the boyars were as independent and troublesome as ever while increasing their hold on the serfs below. The Church blocked any progressive reforms that it saw as irreligious even making it illegal to play chess or gaze at the new moon. This was the condition of Russia when probably its greatest Czar, Peter the Great, took the throne in l682.

Peter I (1682-1725)

is one of the most interesting characters in Russian history. An enormous man (6’8” tall) with incredible physical strength, he had a strong drive and will to match his physical stature. From an early age, Peter was fascinated with anything from Western Europe, especially technology. He was an amateur clockmaker and dentist (to the dismay of anyone in court with a toothache), and especially loved ships. His early exposure to western ways made him realize how backward Russia was compared to the rest of Europe. Therefore, he was determined that Russia should modernize, which meant it must westernize.The first step was the Great Embassy, a grand tour of Europe where Peter traveled in disguise so he could experience its culture and technology more freely. The huge Czar’s identity was the worst kept secret in Europe, but he did learn about such things as Prussian artillery and Dutch and English shipbuilding first-hand instead of from a distance. In their wake, Peter and his wild entourage left a trail of ransacked houses and enough material to keep Europe gabbing for years about these “wild northern barbarians.” But Peter had also gained a much firmer understanding of European technology, further fueling his determination to bring it to Russia, whether Russia wanted it or not. The subsequent transformation of Russia is known as the “Petrine Revolution”.

Peter first had to secure better communications with the West. At this time, Poland and Sweden effectively blocked such contact in order to keep Russia backwards and at their mercy. Peter’s determination to end Russia’s isolation and gain a “window to the West” as he called it, led to The Great Northern War with Sweden (l700-l72l). This was a desperate life and death struggle for both Sweden in its attempt to stay a great power, and for Russia in its effort to become one. Despite the brilliance of Sweden’s brilliant warrior king, Charles XII, Russia’s superior resources and manpower, along with its winter, wore out the Swedes. The “Swedish meteor” which had burned so brightly in the l600s was quickly fading away. In its place, the Russian giant started to cast its huge shadow westward and make Europe take note that a new power had arrived.

Peter’s new capital and “window to the West” was St. Petersburg. Its location was less than ideal, being on marshy land, twenty-five miles from the sea up the Neva River, and in a high northerly latitude that gave up to nineteen hours of sunlight a day in the summer and as little as five hours a day in the winter. Stone for the city had to be brought in on the backs of laborers, since there were no wheelbarrows. As a result, thousands of laborers died while building this new capital which legend said was built on the bones of the Russian people.

Meanwhile, Peter&dsquo;s other reforms left hardly anything untouched. He more tightly centralized the government and built up a more modern army, navy, and merchant marine along European lines. He dealt with his main obstacle to reform, the Orthodox Church, by not electing a new patriarch when the old one died. Without effective leadership, the Church could do little to fight Peter&dsquo;s reforms. After twenty-one years of this, Peter appointed a council, or Holy Synod, which made the Church little more than a department of state.

Peter tried to westernize the economy by first creating mines to develop the resources needed for industry. By l725, Russia had gone from being an iron importer to an iron exporter. He brought in western cobblers to teach Russians how to make western style shoes. Anyone refusing was threatened with life on the galleys. As a result of Peter&dsquo;s strict measures, Russian industries grew, and with them an “industrial serfdom” tied to their jobs in much the same way the peasants were tied to the soil. Peter also worked to build up commerce and a middle class like that he saw in Western Europe. He raised the status of merchants to encourage more men to take up trade and started an extensive canal building program that connected rivers and made water transport possible between the Baltic and Black Seas. Peter tried to westernize people&dsquo;s lifestyles as well. He updated the alphabet and changed the calendar to get more in line with that of the West. He established newspapers, libraries, and western style schools, imported music, theater, and art from the West, and imposed European fashions upon the Russian people. Even beards were taxed, because they were not in style in Europe.

By Peter’s death, Russia’s economy and culture were starting to look much more western. However, many of these reforms were superficial, touching only the nobles or a limited part of the economy. For one thing, such widespread and comprehensive reforms would naturally cause a good deal of resistance and turmoil in such a traditional society as Russia. Therefore, after Peter died, there was a serious reaction against his reforms in an effort to go back to the old ways. However, Peter, by the force of his character, had so thoroughly exposed Russia to the West that there was no turning back. From this point on, like it or not, Russia was a part of Europe.

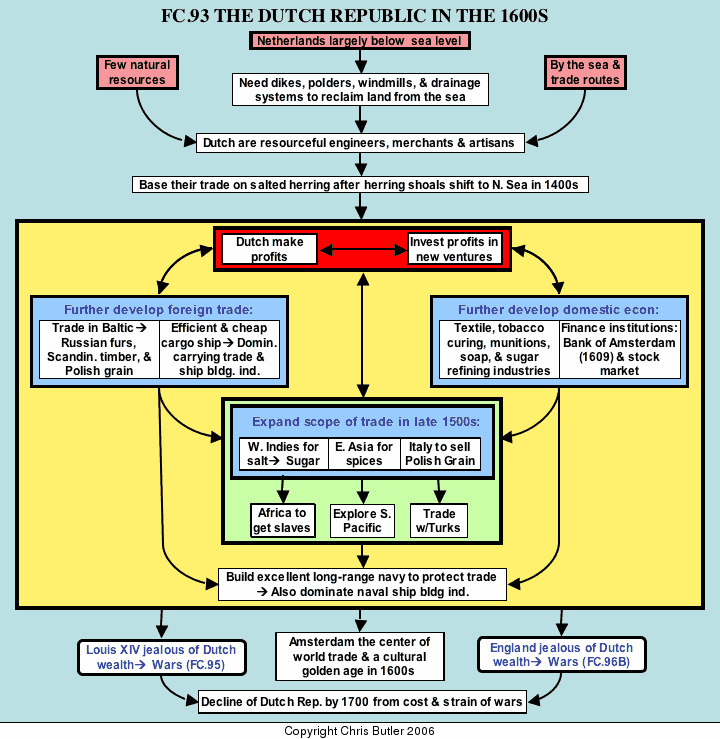

FC93The Rise of the Dutch Republic in the 1600's

Introduction

Although it took the Dutch until 1648 to force formal recognition of their independence from Spain, for all intents and purposes, the Dutch Republic was free by the twelve-year truce signed with Spain in 1609. The question arises: how did the Dutch hold off and defeat the biggest military power in Europe? While geographic distance from Spain, foreign aid from France and England, and the occasional desperate measure of opening their dikes to flood out invading armies all certainly played a role, the single most important factor was money. For example, of the 132 military companies in the Dutch army in 1600, only 17 were actually made up of Dutch soldiers. The rest were English (43), French (32), Scottish (20), Walloon (11), and German (9) companies fighting for the Dutch because they had the money to pay them. The war took a tremendous financial effort to win, costing the Dutch 960,000 florins in 1579, 5.5 million florins in 1599, and 18.8 million florins in 1640. Despite this expense, the Dutch were in stronger financial shape than ever by the end of the war and were well on their way to becoming the dominant commercial and economic power in Europe. This economic dominance was the product of a chain reaction of events and processes that, as so often was the case, was rooted in geography.

Geography of the Netherlands

Three geographic factors influenced the rise of the Dutch Republic. First, as the name Netherlands (literally "lowlands") implies, much of the Dutch Republic is below sea level. The Dutch have waged a constant battle in order to claim, reclaim, and preserve their lands from the sea through the construction of dikes, polders (drained lakes and bogs), drainage systems, and windmills (for pumping out water). Roughly 25% of present day Holland is land reclaimed from the sea and still partially protected by hundreds of windmills. The second factor is the Netherlands' position at the mouths of several major rivers and on the routes between the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean. The third factor is the Netherlands' relative scarcity of natural resources. All three of these factors forced the Dutch to be resourceful engineers, merchants, sailors, and artisans. With these geographic factors as a foundation, the Dutch launched themselves on a career that was a classic case of the old saying: it takes money to make money. The whole process started with fish.

In the 1400's, the herring shoals, a mainstay of the Hanseatic League, migrated from the Baltic to North Sea. The Hanseatic League's loss was the Dutch Republic's gain, since, in the absence of refrigeration, salted herring was then an important source of protein in Europe, especially the Netherlands whose population was 40% urban and had to import about 25% of its food. The other half of this trade was salt for preserving the herring. The best sources of salt were off the coasts of France (the Bay of Biscay) and Portugal. These two activities complemented each other well, since the herring season lasted from June to December, so the Dutch could collect salt from December to June.

The Dutch ran large scale operations compared to those of other countries. Unlike the simple open English fishing boats, the Dutch sailed virtual floating factories, called buses, with barrels of salt for curing the herring on board. Although the claims by other competing countries that the Dutch had 3000 ships working the herring shoals were vastly exaggerated (500 being closer to the mark), the Dutch still produced such a volume of salted herring that they could undersell their competition and drive them out of business.

The Dutch pattern of growth

Dutch control of the herring trade touched off a cycle where the Dutch would get profits, invest those profits in new ventures, which generated more profits and so on. This initially led into two general areas of development, foreign trade and the domestic economy, each of which fed back into the cycle of profits and so on. Both of these also led to expansion of trade across the globe to the Mediterranean, West Indies, Africa, East Indies, and the South Pacific, which also fed back into the cycle of profits.

In terms of foreign trade, the Dutch first expanded their operations into the Baltic Sea where they traded for Norwegian timber, Polish grain, and Russian furs for both home consumption and selling abroad. The Baltic trade became so important that the Dutch referred to it as the "Mother Trade."

All this trade required durable, efficient, and cheaply built ships that could operate in the rough waters of the North and Baltic Seas as well as the shallow coastal waterways that were typical of the Netherlands. What the Dutch came up with was the fluyt , a marvel of Dutch efficiency and engineering. The fluyt was both sturdy enough to withstand rough seas and shallow draught for inland waterways. Unlike other countries' merchant ships, which doubled as warships, the fluyt carried few, if any, guns, leaving extra space for cargo. It was cheaper to build, costing little more than half as much as other ships, thanks to the use of mechanical cranes, wind-driven saws, and overall superior shipbuilding techniques.

The fluyt also had simpler rigging that used winches and tackles, thus requiring a crew of only 10 men compared to 20-30 on other European ships. This resulted in two things. First of all, the Dutch could carry and sell goods for half the price their competition had to charge, giving them control of Europe's carrying trade. Second, they were able to dominate Europe's shipbuilding industry.

Meanwhile, the Dutch were developing their domestic economy in two ways. First they invested in a wide variety of industries, some traditional and some new: textiles, munitions, soap boiling, sugar refining, tobacco curing, glass, and diamond cutting. The need for efficient handling of all the money from this and other enterprises spurred the Dutch to develop another aspect of their economy: financial institutions For one thing, they established the Bank of Amsterdam in 1609, the first public bank in North-West Europe, being modeled after the Bank of Venice (f.1587). The vast sums of cash this bank attracted in deposits allowed it to lower interest rates, which in turn brought in more investments, and so on. Even in wartime, the Bank of Amsterdam was able to lower its interest rates from 12% to 4%. The Dutch also created a stock market. At first this was just a commodities market. Only later did it evolve into a futures commodities market where, by the time a shipload of such goods as wool or tobacco landed, someone had already bought it in the hope of reselling it for a profit.

The success of the Baltic Mother Trade and their domestic economy led the Dutch to expand their foreign trade on a global scale. They did this in three basic directions. First was the Mediterranean, where recurring famines hit in the 1590's, signaling the start of a "Little Ice Age" that would afflict Europe for the next century. This opened new markets for Polish grain, which the Dutch traded in return for, among other things, marble. (It was this Italian marble which Louis XIV would buy from the Dutch for his palace at Versailles.) The Dutch even expanded this Mediterranean trade to include doing business with the Ottoman Turks.

Second, when Portugal (then under Spain's rule) closed access to its supplies of salt, the Dutch crossed the Atlantic to find salt in Venezuela. While there, they found the plantations in the West Indies needed slaves, which got them involved in the African slave trade. They also discovered an even more lucrative condiment in the Caribbean than salt: sugar. Soon, the Dutch were founding their own colonies (e.g., Dutch Guiana) and sugar plantations and gaining control of the sugar trade. Soon, sugar was rivaling even the spices of the Far East in value. However, this is not to say the Dutch ignored the Far Eastern trade.

However, breaking into the lucrative Asian Spice market, the third new direction of Dutch expansion, was not so easy. For one thing, they had to find the East Indies. Amazingly, the Portuguese had kept the South East Passage around Africa a secret for a full century since da Gama's epic voyage. The Dutch looked in vain for a northeast passage around Russia. They also sought a southwest passage, which Oliver van der Noort found (1599-1601), making him the third captain to circumnavigate the globe after Ferdinand Magellan and Sir Francis Drake. But that route was no more practical for the Dutch than it had been for the Spanish and English.

Finally, Jan van Linschuten, a Dutch captain who had served Portugal, showed the way around Africa in 1597. Although the first voyage was not a financial success, the second was, bringing back 600,000 pounds of pepper and 250,000 pounds of cloves worth 1.6 million florins, double the initial investment. Investors rushed to get in on the action, forming the Dutch East Indies Company in 1602. This privately owned company operated virtually as an independent state, seizing control of the spice trade from Portugal's weakening grip. From there, always in search of new markets, the Dutch explored the South Pacific, discovering Australia, New Zealand, and Tasmania, the last two names bearing evidence of their presence.

Such a far-flung trading empire, combined with the struggle with Spain, required a navy to protect its merchant ships. Therefore, the Dutch developed such a navy, excelling in this as well as their other endeavors. At this point, warships generally followed the principle of the bigger the better. As a result, the man-of-war, as it was called, was a huge and bulky gun platform that did not suit the Dutch needs. For one thing, they needed more of a shallow draught vessel that could sail in their home waters. They also needed a long-range ship that could protect their far-flung commercial interests. The result was the frigate, a sleeker shallow draught vessel with only about 40 guns, but capable of long-range voyages. Dutch frigates, along with their excellent sailors and captains, made the Dutch the supreme naval power of the early 1600's and also helped them dominate the warship-building industry, building navies for both sides in a Danish-Swedish war and even for their French rivals. And, of course, this brought in more money and pushed the Dutch to expand their domestic industries and finance operations in three ways.

A cultural golden age

By the early 1600's, Amsterdam was the center of world trade, which allowed the Dutch to engage in one more type of activity: patronage of the arts. The seventeenth century saw the Dutch Republic become the center of a cultural flowering much as Italy had been during its Renaissance. Along with money to patronize the arts and sciences, the Dutch Republic had both a free and tolerant atmosphere and enterprising spirit willing to challenge old notions and creatively expand the frontiers of the arts and sciences. The Dutch Republic acted as a virtual magnet for Jewish émigrés from Spain and Portugal and Calvinist dissidents from England, some of who would eventually move on to Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts. The Jewish philosopher from Spain, Spinoza, and the French mathematician, Descartes, were two of the shining lights that the Dutch attracted. Notable among Dutch artists were Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hals, Van Dyck, Steen, Ruysdael, and Hobbema, whose portraits, domestic scenes, landscapes, and mastery of light and shadow brought their age to life on the canvass as no artists before them had done.

Conclusion

The Golden Age of the Dutch Republic was to be short lived, once again largely because of geography. It was the Dutch Republic's great misfortune to border the great land power of the day, France. In the 1670's, the French king, Louis XIV, due to a combination of jealousy of Dutch prosperity and hatred of Protestants, launched a series of wars that would embroil most of Europe and put the Dutch constantly on the front line of battle. At the same time, just across the channel, the growing economic and naval power, England, was challenging the Dutch on the high seas and in the market place. Three brief but sharply fought naval wars plus the strain of fighting off Louis exhausted the Dutch and allowed England to become the premier economic, naval, and colonial power in the world by the 1700's. However, England owed the techniques and innovations for much of what it would accomplish in business and naval development to the Dutch from the previous century.

FC93AThe "Tulipmania" of the 1630s

The tulip seems to have originated in the harsh wind-blown environment of the Himalayas. It was originally a short, stubby flower, but was admired for its beauty and as a symbol of the tenacity of life. Tulips spread westward and became especially popular among the Arabs who cultivated gardens of them. Their popularity spread to the Turks, and the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent even had a tattoo of a tulip to serve as a protective talisman.

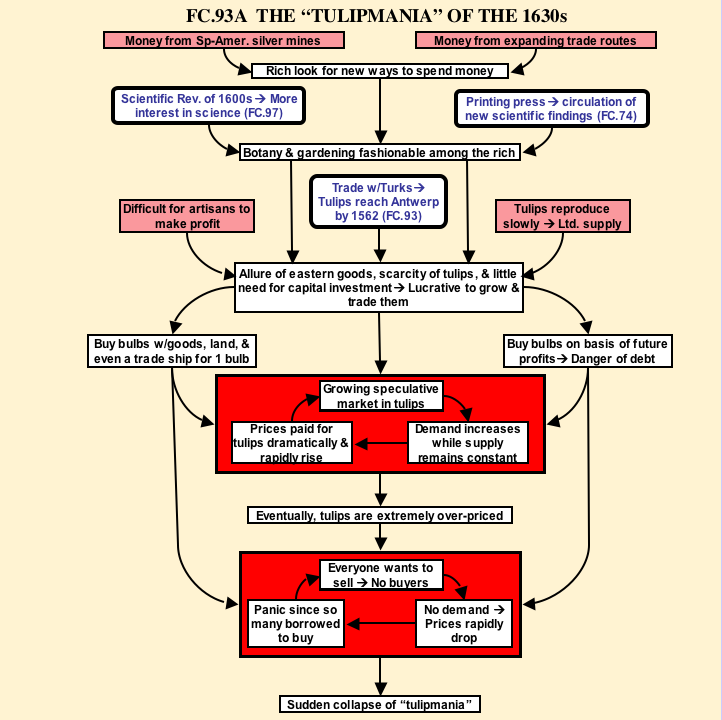

The tulip first arrived in Antwerp in 1562 by way of trade with the Turks. By this time, the influx of money from the Americas and expanding trade routes were pushing rich Europeans to look for new ways to spend and invest their money. One area was botany and gardening, thanks to the scientific revolution and the circulation of scientific knowledge by the printing press. This and two other factors made the tulip seem like the perfect thing in which to invest. One was that it was difficult for many Dutch artisans to make a profit, so they were also looking for another source of income requiring little capital investment. The other factor was that tulips reproduce slowly, thus creating a limited supply that could be sold for a high profit. All these things made tulips lucrative to grow and sell.

At first, the tulip trade grew reasonably, as demand for this new sensation grew and the supply remained constant, thus driving prices up. This would draw more people into the speculative market, further increasing demand, driving prices up more, and so on. However, what started as a reasonable trade in tulips soon turned into a frenzy of buying and selling, with each new buyer expecting to be able to sell at a higher price. People were paying outrageous prices, such as plots of land and, a whole trade ship, and, in one case, an entire mansion, for a single bulb. They were also borrowing heavily and going into debt to buy tulip bulbs, counting on future profits from other people caught up in the same frenzy.

Unfortunately, there was a major problem with tulip bulbs, because the most beautiful designs in tulips tend to be recessive traits, and there was no guarantee that a tulip bulb’s offspring would have the same traits as its parent. Eventually, people, realizing this and seeing that tulips were extremely over-priced, wanted to sell their bulbs. Unfortunately, there were no buyers, so prices dropped rapidly. This led to panic selling, since so many people were in debt for tulip bulbs they hoped to sell, causing prices to drop more, leading to more panic selling, and so on. By the end of 1637, the tulip bubble had burst and “tulipmania had collapsed as suddenly as it had bloomed.

Even though the speculative bubble popped, tulips still retained much of their value. Louis XIV would buy 2,000,000 tulips a year from the Dutch for his palace at Versailles. They continue to be a major export for Holland (the Dutch Republic).

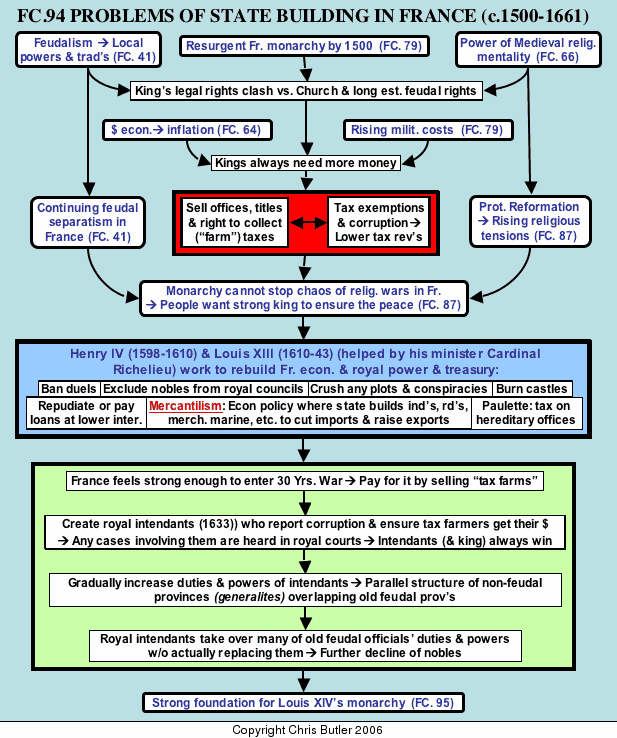

FC94Laying the Foundations for Absolutism in France and Europe

The roots of the problems of state building in the 1600's, go back to the turmoil of the Dark Ages which helped give rise to two medieval institutions: feudalism and the medieval Church. Feudalism formalized the fragmentation of France into some 300 different legal systems. Over the centuries, custom and tradition firmly established a multitude of local rights and privileges across France. Various nobles and local officials claimed these rights, privileges, and the offices that went with them as their patrimonial birthrights. Meanwhile, the chaos of the age helped make the medieval Church a major factor in state and society. However, the revival of towns and trade in the High Middle Ages helped lead to the rise of kings. They had always been recognized in theory as the rulers of France, but it had been centuries since anyone had taken them seriously.

By the 1200's kings were making serious claims to rule in fact as well as name, strengthening those claims with the doctrine of Divine Right of Kings. However, they were continually clashing with the Church and the locally entrenched rights and privileges that had evolved during the Dark Ages. French courts, known as Parlements, were particularly troublesome in modifying, slowing down, or even stopping the king's decrees from being carried out. The king could appear before the Parlements and plead his case, but that was seen as being beneath his royal dignity and was rarely done.

This made it especially difficult for kings to get new taxes, which the inflation and high military costs of the 1500's made even more necessary. Kings had to resort to such fund raising techniques as taking out loans and selling offices and noble titles to ambitious members of the middle class. Unfortunately, these created even bigger problems. Kings repaid loans through tax farming where creditors would collect the taxes of certain provinces. Naturally, these creditors would take everything they could get from the provinces, which bred widespread corruption and discontent in the absence of a professional bureaucracy to check these abuses. Selling offices and noble titles also bred corruption and made their owners tax exempt. All this merely reduced the king's tax base even more, forcing him to sell more offices and tax farms, and so on until he was so far in debt he would declare bankruptcy or imprison his creditors on charges of corruption in order to erase his debts.

By the mid 1500's, these financial problems, combined with growing religious turmoil and continuing feudal separatism, helped trigger the French Wars of Religion which devastated France on and off for nearly forty years (1562-98). One outcome of these wars was the willingness of people to recognize the king's power in order to ensure the peace. The new king, Henry IV (1598-1610), and his minister, Sully, used this new attitude favoring absolutism and various economic measures to restore the power of the monarchy. First of all, they repudiated all foreign debts, while repaying French creditors at a much lower rate of interest. Second, they established the Paulette, a tax on hereditary offices that would partially make up for lost revenues when commoners bought into the tax-exempt ranks of the nobility. Third, they built and repaired roads and bridges to encourage internal trade. Finally, in the spirit of the economic theory of the day, mercantilism, which encouraged domestic industries to increase the flow of gold and silver into a country, they promoted such luxury industries as silk and tapestries to compete with foreign industries. By the end of Henry's reign, the royal government was probably as financially solid as it had ever been.

Henry's successor, Louis XIII (1610-43), and his minister, Cardinal Richelieu, continued building royal power. They particularly focused on breaking the power of the nobles by destroying their castles, quickly crushing any of their conspiracies, and infringing on their privileges (such as dueling). They also excluded them from royal councils, relying more on middle class officials who had just recently bought noble titles and were thus more reliable. By 1635, they felt France was strong enough to throw its weight into the Thirty Years War to stop Spain. Unfortunately, the war's expense largely wrecked the progress of the last 35 years and forced Richelieu to resort increasingly on tax farming, but this time with one important innovation.

In order to protect the financiers who bought the tax farms, Richelieu created new officials known as Intendants, whose job was to report corruption and make sure the financiers got their money. Naturally, both the financiers and intendants were quite unpopular, and got involved in numerous disputes. However, since the intendants were new officials with no tradition of being tried in local or Church courts, all their cases went to the royal courts, which favored them and the king's interests. Eventually, Richelieu expanded the intendants' authority, making them supreme in all provincial affairs and rearranging the provinces into 32 non-feudal districts known as generalites. This neatly sidestepped the firmly entrenched interests of local authorities and laid the foundations for more thorough royal control of the provinces and France under Louis XIV.

FC95The Age of Louis XIV, the "Sun King" (1643-1715)

I am the state.— Voltaire, incorrectly quoting Louis XIV

Introduction

From 1643 to 1815 France dominated much of Europe's political history and culture. Foreigners came to France, preferring it to the charms of their own homeland. Even today, many still consider it the place to visit in Europe and the world. In the 1600's and 1700's there was a good reason for this dominance: population. France had 23,000,000 people in a strongly unified state compared to 5,000,000 in Spain and England, and 2,000,000 in the Dutch Republic and the largest of the German states. This reservoir of humanity first reached for and nearly attained the dominance of Europe under Louis XIV, the "Sun King".

Louis' early life and reign (1643-61)

Louis was born in 1638 and succeeded his father, Louis XIII, as king in 1643 at the age of five. Luckily, another able minister and Richelieu's successor, Cardinal Mazarin, continued to run the government. In 1648, encroachment by the government on the nobles' power, poor harvests, high taxes, and unemployed mercenaries plundering the countryside after the Thirty Years War led to a serious revolt known as the Fronde, named after the slingshot used by French boys. Louis and the court barely escaped from Paris with their lives. Although Mazarin and his allies crushed the rebels after five hard years of fighting (1648-53), Louis never forgot the fear and humiliation of having to run from the Parisian mob and fight for his life and throne against the nobles. This bitter experience would heavily influence Louis' policies when he ruled on his own.

From 1643 to 1661, Cardinal Mazarin ruled ably in the young king's interests, although he provided Louis with a rather odd upbringing for a king. Despite an immense fortune, Mazarin was something of a miser who gave the young king inadequate food, clothing, and attention. (Once the young Louis was left unattended and fell into a fountain where he almost drowned.) Louis also got little in the way of a formal education and, even as an adult, was barely literate. But Mazarin did give Louis a sense of what it meant to be a king. As a result, he turned out to be a hard working ruler, but often lacked much common sense and the willingness to entrust enough freedom of action to his subordinates. From his mother, a full-blooded Spanish princess, Louis learned great religious piety and love of ritual, another trait that would influence his reign. In 1661, Mazarin died. Louis' officials, assuming he would be a "do nothing" king like his father, asked to whom they should now answer. Louis' reply was "To me." The age of Louis XIV was about to begin in earnest.

Louis' internal policies

Louis XIV may not have said, "I am the state", but he ruled as if he had said it. Louis was the supreme example of the absolute monarch, and other rulers in Europe could do no better than follow his example. Although Louis wished to be remembered as a great conqueror, his first decade of active rule was largely taken up with building France's internal strength. There are two main areas of Louis' rule we will look at here: finances and the army.

Louis' finance minister, Jean Baptiste Colbert, was an astute businessman of modest lineage, being the son of a draper. Colbert's goal was to build France's industries and reduce foreign imports. This seventeenth century policy where a country tried to export more goods and import more gold and silver was known as mercantilism. While its purpose was to generate revenue for the king, it also showed the growing power of the emerging nation state. Colbert declared his intention to reform the whole financial structure of the French state, and he did succeed in reducing the royal debt by cutting down on the number of tax farms he sold and freeing royal lands from mortgage. Colbert especially concentrated on developing France's economy in three ways.

First of all, Colbert concentrated on developing French internal trade in order to reduce foreign imports. He developed better inland trade routes by building canals and improving ports and river ways, which would connect different parts of the country to each other and open up new markets. Secondly, Colbert worked to develop French industries. Most industries he developed can be seen as being aimed against imports from other countries: mirrors from Venice, lace from England, and iron and firearms from Sweden. He also built a merchant marine to stop foreign powers, especially the Dutch, from carrying French goods and making profits at France's expense. In 1661, France had a merchant marine of 18 ships. By 1681, it was up to 276 ships. Finally, Colbert encouraged the development of overseas colonies much like those of other European powers. During this time, France established and tightened control over colonies in Canada, French Guiana, and Madagascar.

For all his efforts and financial wizardry, Colbert's successes were limited, largely because he was trying to drag a basically medieval economy into the modern world. Guilds were still powerful and held back progress in new production and financing techniques. Local authorities still jealously guarded their rights to charge tolls on trade. Getting across France involved paying up to 100 such local tolls, which of course stifled trade. The tax burden was extremely unfair, with nobles and the Church virtually exempt from taxation even though they controlled much of the land. Colbert's own techniques of having the government control so many aspects of the economy were heavy handed and tended to stifle initiative. His efforts at trying to centrally control France's overseas colonies were especially disastrous.

However, Colbert did make real progress in developing the French economy. A merchant marine and navy were built. Industries were developed. And for a few years Colbert even managed to run the government at a profit. Unfortunately, Louis' desire for glory and conquests led to a long series of wars that embroiled Europe in a new round of bloodshed and wrecked France's economy. Not even Colbert could do anything to stop that.

The army was another primary object of reform. By the mid 1600's, the old system of recruiting armies and fighting wars was clearly outmoded. Mercenaries were disloyal, untrustworthy, and terribly destructive to friend and foe alike. By contrast, the Swedish army of Gustavus Adolphus and the English army of Oliver Cromwell each had loyal native recruits that proved reliable and effective, while Brandenburg-Prussia was transforming its troublesome nobles into a loyal professional officer corps. These lessons were not lost on Louis and his minister of war, Louvois, who built what amounted to one of the first modern national armies. Three aspects of the army they concentrated on were its training and discipline, its equipment, and its supplies.

First of all, soldiers in Louis' new army, whether mercenaries or peasant draftees, found military life was much stricter and more regularized in several ways. For one thing, instead of mercenary captains who recruited, paid, and commanded them, soldiers now answered to the state and its officers. Along these lines, there was also a regular chain of command from the Intendant de l'armee (roughly equivalent to our modern secretary of defense) down through field marshals, generals, colonels, and captains. Officers also got regular training and were much more strictly under the rule of the central government than ever before.

Naturally, the nobles claimed the officers' positions as their birthright. However, the government kept tighter control of its army, largely through new positions filled by men of more humble birth. These lieutenant colonels performed many vital duties in lieu of the noble officers without actually replacing them. In this way, a more modern army helped Louis bring the old troublesome medieval nobility more tightly under his control.

A second reform was that uniforms and equipment were more standardized, which made the army easier to supply, more efficient, and promoted more of a group identity and higher morale. Finally, the army maintained regular supply lines. This reduced the need for foraging, which increased discipline and control over the army and protected the civilian populace from being plundered.

There were two major factors that limited the effectiveness of Louis' military reforms. For one thing, Louis's standing army was large and expensive, having some 400,000 men at its height. It is estimated that a pre-industrial society such as seventeenth century France could only afford to support 1% of its population in the military. Louis' army at its height was nearly twice that, which was a terrible strain on French society. This became especially apparent in Louis' later wars when supply lines broke down, which led to foraging and a breakdown in discipline. Second, the expense of Louis' wars forced him to sell military offices, which brought in less capable and dedicated officers. Overall, Louis' military reforms were much like Colbert's economic reforms. They made progress, but met severe obstacles that prevented them from being completely successful.

Despite these limits to Louis' economic and military reforms, France was the most powerful state in Europe by the late 1660's. Louis realized this quite well, in fact probably too well, because he embarked on an ambitious series of policies that nearly ruined France by the end of his reign. There were three areas where Louis chose to show his power: religion, his palace at Versailles, and foreign expansion.

Religion

was one aspect of Louis' reign that illustrated the absolute nature of his monarchy quite well. Louis himself was quite a pious Catholic, learning that trait from his mother. However, in the spirit of the day, he saw religion as a department of state subordinate to the will of the king. By the same token, not adhering to the Catholic faith was seen as treason.As a result, Louis gradually restricted the rights of the French Huguenots and finally, in 1685, revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had given them religious freedom since the end of the French Wars of Religion in 1598. This drove 200,000 Huguenots out of France, depriving it of some of its most skilled labor. Thus Louis let his political and religious biases ruin a large sector of France's economy.

Versailles