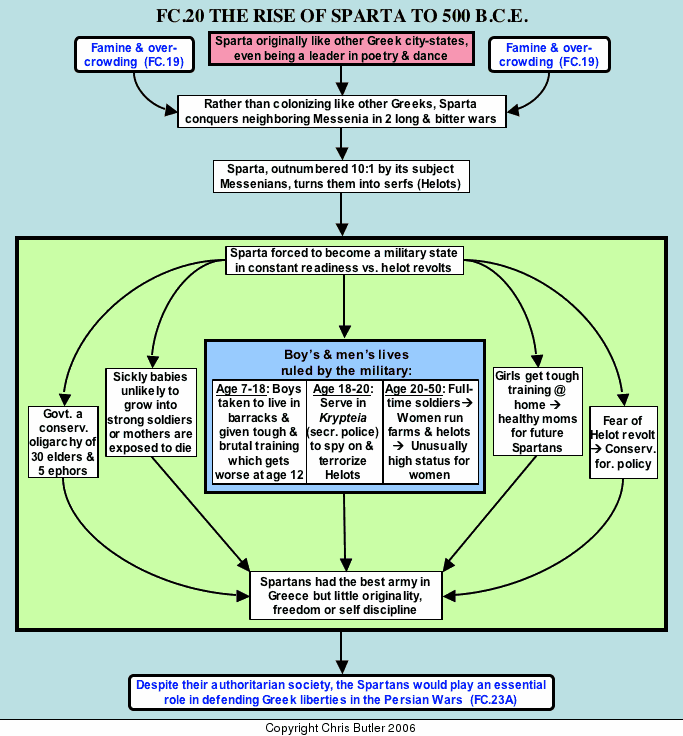

FC20The Rise of Sparta to 500 BCE

Come home with your shield or on it.— Spartan women, to their men leaving for battle

No Greek city-state aroused such great interest and admiration among other Greeks as Sparta. This was largely because the Spartans did about everything contrary to the way other Greeks did. For example, Sparta had no fortifications, claiming its men were its walls. While other Greeks emphasized their individuality with their own personal armor, the Spartans wore red uniforms that masked their individuality and any blood lost from wounds. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that we remember Sparta for being a military state always ready for war, but not against other city-states so much as against its own enserfed subjects.

Originally, Sparta was much like other Greek city-states, being a leader in poetry and dance. However, by 750 B.C.E., population growth led to the need for expansion. Instead of colonizing overseas, like other Greeks did, the Spartans decided to attack their neighbors, the Messenians. In two bitterly fought wars, they subdued the Messenians and turned them into serfs ( Helots) who had to work the soil for their masters. Unfortunately for the Spartans, the Helots vastly outnumbered them.

As a result, Sparta became a military state constantly on guard against the ever-present threat of a Helot revolt. This especially shaped five aspects of Spartan society: its infants, its boys, its girls, its government, and its foreign policy. Infants were the virtual property of the state from birth when state inspectors would examine them for any signs of weakness or defects. Babies judged unlikely to be able to serve as healthy soldiers or mothers were left to die on nearby Mt. Taygetus.

Boys were taken from home at age seven to live in the barracks. There they were formed into platoons under the command of an older man and the ablest of their number. Life in the barracks involved a lot of hard exercise and bullying by the older boys. At age twelve it got much worse. Adolescence brought the Spartan training at its worst. The boys received one flimsy garment, although they usually trained and exercised in the nude. They slept out in the open year round, only being allowed to make a bed of rushes that were picked by hand, not cut. They were fed very little, forcing them to steal food to supplement their diet and teaching them to forage the countryside as soldiers. Their training, games, and punishments were all extremely harsh. One notorious contest involved tying boys to the altar of Artemis Orthia and flogging them until they cried out. Reportedly, some of them kept silent until they died under the lash.

At age eighteen, the Spartan entered the Krypteia, or secret police, for two years. The Krypteia's task was to spy on and terrorize the Helots in order to keep them from plotting revolt. The Spartans even declared ritual warfare on the Helots each year to remind themselves and the Helots of their situation and Spartan resolve to deal with it. At age twenty, the Spartan entered the army where he would spend the next thirty years. As an adult, he could grow his hair shoulder length in the Spartan fashion to look more terrifying to his enemies. Not surprisingly, he had little in the way of a family life. However, it was illegal not to marry in Sparta, since it was part of the Spartan's duty to produce strong healthy children for the next generation. After getting married, the young husband might have to sneak out of the barracks at night in order to see his wife and children. It was said some Spartan fathers went for years without seeing their families by the light of day. At age fifty, the Spartan could finally move home, although he remained on active reserve for ten more years.

Girls did not have it much easier. Although they did live at home rather than in the barracks, they also went through arduous training and exercise. All of this was for one purpose: to produce strong healthy children for the next generation. Surprisingly, Spartan women were the most liberated women in ancient Greece. This was because the men were away with the army, leaving the women to supervise the Helots and run the farms. In fact, Spartan women scandalized other Greeks with how outspoken and free they were.

Spartan government, in sharp contrast with the democracies found in other city-states, kept elements of the old monarchy and aristocracy. They had two kings whose duty was to lead the army. Most power rested with five officials known as ephors and a council of thirty elders, the Gerousia. There was also an assembly of all Spartan men that voted only on issues the Gerousia presented them. The Spartans had a very conservative foreign policy, since they did not want to risk a Helot revolt while they were away at war. They did extend their influence through leadership of the Peloponnesian League, which contained most of the city-states in the Peloponnesus, making Sparta the most powerful Greek city-state, although its army was never very large.

Spartan discipline did produce magnificent soldiers, inured to hardship and blind obedience to authority, but with little talent for original thinking or self-discipline. However, in the Persian wars, the Spartans would do more than their share in the defense of freedom, as ironic as that may have sounded to them.