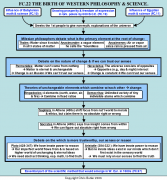

FC22: Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle (c.600-300 BCE)

Flowchart

Introduction

When people think of the ancient Greeks, they usually think of such things as Greek architecture, literature, and democracy. However, there is one other contribution they made that is central to Western Civilization: the birth of Western science.

There were three main factors that converged to help create Greek science. First of all, there was the influence of Egypt, especially in medicine, which the Greeks would draw heavily upon. Second, Mesopotamian civilization also had a significant impact, passing on its math and astronomy, including the ability to predict eclipses (although they did not know why they occurred). Third, there was the growing prosperity and freedom of expression in the polis, allowing the Greeks to break free of older mythological explanations and come up with totally new theories. All these factors combined to make the Greeks the first people to give non-mythological explanations of the universe. Such non-mythological explanations are what we call science.

However, there were also three basic limitations handicapping Greek scientists compared to scientists today. For one thing, they had no concept of science as we understand it. They thought of themselves as philosophers (literally "lovers of wisdom") who were seeking answers to all sorts of problems about their world: moral, ethical, and metaphysical as well as physical. The Greeks did not divide knowledge into separate disciplines the way we do. The philosopher, Plato, lectured on geometry as well as what we call philosophy, seeing them as closely intertwined, while Parmenides of Elea and Empedocles of Acragas wrote on physical science in poetic verse. Second, the Greeks had no guidelines on what they were supposed to be studying, since they were the first to ask these kinds of questions without relying on religious explanations. However, they did define certain issues and came up with the right questions to ask, which is a major part of solving a problem. Finally, they had no instruments to help them gather data, which slowed progress tremendously.

The Milesian philosophers

Greek science was born with the Ionian philosophers, especially in Miletus, around 600 B.C.E. The first of these philosophers, Thales of Miletus, successfully predicted a solar eclipse in 585 B.C.E., calculated the distance of ships at sea, and experimented with the strange magnetic properties of a rock near the city of Magnesia (from which we get the term "magnet"). However, the question that Thales and other Ionian philosophers wrestled with was: What is the primary element that is the root of all matter and change? Thales postulated that there is one primary element in nature, water, since it can exist in all three states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas.

Thales' student, Anaximander, proposed the theory that the stars and planets are concentric rings of fire surrounding the earth and that humans evolved from fish, since babies are too helpless at birth to survive on their own and therefore must arise from simpler more self-sufficient species. He disagreed with Thales over the primary element, saying water was not the primary element since it does not give rise to fire. Therefore, the primary element should be some indeterminate element with built-in opposites (e.g., hot vs. cold; wet vs. dry). For lack of a better name, he called this element the "Boundless." Another Milesian, Anaximenes, said the primary element was air or vapor, since rain is pressed from the air.

The nature of change

All these speculations were based on the assumption there is one eternal and unchanging element that is the basis for all matter. Yet, if there is just one unchanging element, how does one account for all the apparent diversity and change one apparently sees in nature? From this time, Greek science was largely split into two camps: those who said we can trust our senses and those who said we cannot.

Among those who distrusted the senses was Parmenides of Elea, who, through some rather interesting logic, said there is no such thing as motion. He based this on the premise that there is no such thing as nothingness or empty space since it is illogical to assume that something can arise from nothing. Therefore, matter cannot be destroyed, since that would create empty space. Also, we cannot move, since that would involve moving into empty space, which of course, cannot exist. The implication was that any movement we perceive is an illusion, thus showing we cannot trust our senses.

On the other hand, there was Heracleitus of Ephesus, who said the world consists largely of opposites, such as day and night, hot and cold, wet and dry, etc. These opposites act upon one another to create change. Therefore not only does change occur, but is constant. As Heracleitus would say, you cannot put your foot into the same river twice, since it is always different water flowing by. However, since we perceive change, we must trust our senses at least to an extent.

A partial reconciliation of these views was worked out by two different philosophers postulating the general idea of numerous unchanging elements that could combine with each other in various ways. First, there was Empedocles of Acragas who said that the mind can be deceived as well as the senses, so we should use both. This led to his theory of four elements, earth, water, air, and fire, where any substance is defined by a fixed proportion of one or more of these elements (e.g., bone = 4 parts fire, 2 parts water, and 2 parts earth). Although the specifics were wrong, Empedocles' idea of a Law of Fixed Proportions is an important part of chemistry today.

In the fifth century B.C.E., Democritus of Abdera developed the first atomic theory, saying the universe consists both of void and tiny indestructible atoms. He said these atoms are in perpetual motion and collision causing constant change and new compounds. Differences in substance are supposedly due to the shapes of the atoms and their positions and arrangements relative to one another.

In the fifth century B.C.E., Athens, with its powerful empire and money, became the new center of philosophy, drawing learned men from all over the Greek world. Many of these men were known as the Sophists. They doubted our ability to discover the answers to the riddles of nature, and therefore turned philosophy's focus more to issues concerning Man and his place in society. As one philosopher, Protagoras, put it, "Man is the measure of all things." Being widely traveled, the Sophists doubted the existence of absolute right and wrong since they had seen different cultures react differently to moral issues, such as public nudity, which did not bother the Greeks. As a result, they claimed that morals were socially induced and changeable from society to society. Some Sophists supposedly boasted they could teach their students to prove the right side of an argument to be wrong. This, plus the fact that they taught for money, discredited them in many people's eyes.

Socrates (470-399 B.C.E.)

was one of Athens' most famous philosophers at this time. Like the Sophists, with whom he was wrongly associated, he focused on Man and society rather than the forces of nature. As the Roman philosopher, Cicero, put it, "Socrates called philosophy down from the sky..." Unlike the Sophists, he did not see morals as relative to different societies and situations. He saw right and wrong as absolute and worked to show that we each have within us the innate ability to arrive at that truth. Therefore, his method of teaching, known even today as the Socratic method, was to question his students' ideas rather than lecture on his own. Through a series of leading questions he would help his students realize the truth for themselves.Unfortunately, such a technique practiced in public tended to embarrass a number of people trapped by Socrates' logic, thus making him several enemies. In 399 B.C.E., he was tried and executed for corrupting the youth and introducing new gods into the state. Although Socrates left us no writings, his pupil Plato preserved his teachings in a number of written dialogues. Socrates influenced two other giants in Greek philosophy, Plato and Aristotle, who both agreed with Socrates on our innate ability to reason. However, they differed greatly on the old question of whether or not we can trust our senses.

Plato (428-347)

was the first of these philosophers. He was also influenced by the early philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras of Croton in South Italy, who is most famous for the Pythagorean theorem for finding the length of the hypotenuse in a right triangle. Pythagoras thought that all the principles of the universe were bound up with the mystical properties of numbers. He felt the whole universe can be perceived as a harmony of numbers, even defining objects as numbers (e.g., justice = 4). He saw music as mathematical and, in the process, discovered the principles of octaves and fifths. He also thought the universe orbited around a central fire, a theory that would ultimately influence Copernicus in his heliocentric theory 2000 years later.Plato drew upon Pythagoras' idea of a central fire and proposed there are two worlds: the perfect World of Being and this world, which is the imperfect World of Becoming where things are constantly changing. This makes it impossible for us to truly know anything, since this world is only a dim reflection of the perfect World of Being. As Plato put it, our perception of reality was no better than that of a man in a cave, trying to perceive the outside world through viewing the shadows cast against the wall of the cave by a fire. Since our senses alone cannot be trusted, Plato said we should rely on abstract reason, especially math, much as Pythagoras had. The sign over the entrance to Plato's school, the Academy, reflected this quite well: "Let no one unskilled in geometry enter."

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.)

was a pupil at Plato's Academy, but held a very different view of the world from his old teacher, believing in the value of the senses as well as the mind. Although he agreed with Plato on our innate power of reasoning, he asserted that nothing exists in our minds that does not first exist in the sensory world. Therefore, we must rely on our senses and experiment to discover the truth.Aristotle accepted the theory of four elements and the idea that the elements were defined on the basis of two sets of contrasting qualities: hot vs. cold, and wet vs. dry, with earth being cold and dry, water being cold and wet, air being hot and wet, and fire being hot and dry. Thus, according to Aristotle, we should be able to change substances by changing their qualities. The best example was heating cold and wet water to make it into hot and wet air (vapor). This idea would inspire generations of alchemists in the fruitless pursuit of a means of turning lead into gold.

Aristotle said the four elements have a natural tendency to move toward the center of the universe, with the heavier substances (earth and water) displacing the lighter ones (air and fire), so that water rests on land, air on top of water, and fire on top of air. He also said there was a celestial element, ether, which was perfect and unchanging and moved in perfect circles around the center of the universe, which is earth where all terrestrial elements are clustered.

Aristotle's theories of the elements and universe were highly logical and interlocking, making it hard to disprove one part without attacking the whole system. Although Aristotle often failed to test his own theories (so that he reported the wrong number of horse's teeth and men's ribs), his theories were easier to understand than Plato's and reinstated the value of the senses, compiling data, and experimenting in order to find the truth. Although Plato's theories would not be the most widely accepted over the next 2000 years, they would survive and be revived during the Italian Renaissance. Since then, the idea of using math to verify scientific theories has also been an essential part of Western Science. While both Plato and Aristotle had flaws in their theories, they each contributed powerful ideas that would have profound effects on Western civilization for 2000 years until the Scientific Revolution of the 1700's.