FC23: The Delian League and the Athenian Empire (478-431 BCE)

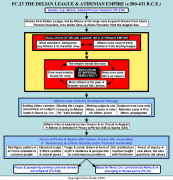

Flowchart

Formation of the Delian League

We can well imagine the Greeks' incredible feelings of pride and accomplishment in 478 B.C.E. after defeating the Persian Empire. The Athenians felt that they in particular had done more than their part with their army at Marathon and their navy at Salamis and Mycale. It was this incredible victory which gave them the self-confidence and drive to lead Greece in its political and cultural golden age for the next half century.

However, victory had been won at a heavy price. Fields, orchards, and vineyards lay devastated throughout much of Greece, and it would take decades for the vineyards and olive groves in particular to be restored. Athens itself was in ruins, being burned by the Persians in vengeance for the destruction of Sardis during the Ionian Revolt. Therefore, the Athenians immediately set to work to rebuild their city, and in particular its fortifications. The Spartans, probably through fear or jealousy of Athens' growing power, tried to convince the Athenians not to rebuild their walls. They said that if the Persians came back and recaptured Athens, they could use it as a fortified base against other Greeks. The Athenian leader, Themistocles, stalled the Spartans on the issue until his fellow Athenians had enough time to erect defensible fortifications. (This was later extended by what was known as the Long Walls to connect Athens to it port, Piraeus, so it could not be cut off from its fleet.) By the time Sparta realized what was happening, it was too late to do anything. One could already see bad relations starting to emerge between Athens and Sparta. In time, they would get much worse.

Since the Athenians and other Greeks could not assume that the Persians would not come back, they decided the best defense was a good offense, and formed an alliance known as the Delian League. The League's main goals were to liberate the Ionian Greeks from Persian rule and to safeguard the islands in the Aegean from further Persian aggression. The key to doing this was sea power, and that made Athens the natural leader, since it had by far the largest navy and also the incentive to strike back at Persia. At first, Sparta had been offered leadership in the league because of its military reputation. However, constant fear of Helot revolts made the Spartans reluctant to commit themselves overseas. Also, their king, Pausanias, had angered the other Greeks by showing that typical Spartan lust for gold. As a result, he was recalled, leaving Athens to lead the way.

The Persian navy, or what was left of it, was in no shape to halt the Greek advance after taking two serious beatings from the Greeks in the recent war. Ionia was stripped from the Great King's grasp, and the Persians were swept from the Aegean sea island by island. Within a few years, the Delian League controlled virtually all the Greeks in the islands and coastal regions of the Aegean.

From Delian League to Athenian Empire

At first each polis liberated from Persia was expected to join the league and contribute ships for the common navy. However, most of these states were so small that the construction and maintenance of even one ship was a heavy burden. Therefore, most of these states started paying money to Athens which used their combined contributions to build and man the League's navy. This triggered a feedback cycle where Athens came to have the only powerful navy in the Aegean, putting the other Greeks at its mercy. Athens could then use its navy to keep league members under control, forcing them to pay more money to maintain the fleet which kept them under control, and so on.

The changing nature of the league became apparent a decade after the defeat of the Persians when the island states of Naxos (469 B.C.) and Thasos (465 B.C) felt secure enough to try to pull out of the League. However, Athens and its navy immediately pushed them back in, claiming the Persian threat was still there. The Naxians and Thasians could do little about it since the only navy they had was the one they were paying Athens to build and man. And that was being used to keep them inthe League so they could keep paying Athens more money. The Delian League was turning into an Athenian Empire.

The cycle supporting Athens' grip on its empire also supported (and was itself reinforced by) another feedback loop that expanded and supported the Athenian democracy. It started with the empire needing the fleet as its main source of power and control. Likewise, the fleet needed the poor people of Athens to serve as its rowers. Since these people, even more than the middle class hoplites, were the mainstay of Athens' power, they gained political influence to go with their military importance, thus making Athens a much more broadly based democracy. The poor at Athens in turn needed the empire and its taxes to support their jobs in the fleet and their status in Athens. This fed back into the empire needing the navy, and so on.

The Athenian democracy likewise strongly enforced collection of league dues to maintain what in essence was now an "imperial democracy. Thus the navy was the critical connecting link between empire and democracy, holding the empire together on the one hand, while providing the basis for democratic power on the other. The Athenian democratic leader, Pericles, especially broadened Athenian democracy by providing pay for public offices so the poor could afford to participate in their polis' government.

Athens further tightened its hold on its empire by settling Athenian citizens in colonies ( cleruchies) on the lands of cities it suspected of disloyalty, making their subjects come to Athens to try certain cases in Athenian courts, thus supplying them with extra revenues, and moving the league treasury from its original home on the island of Delos to Athens where the Athenians claimed it would be safer from Persian aggression. Athens installed or supported democracies in its subject states, feeling they would be friendlier to Athenian policies since they owed their power to Athens. It also allowed the minting and use of only Athenian coins. This provided the empire with a stable and standard coinage as well as exposing everyone in the empire to Athenian propaganda every time they looked at a coin and saw the Athenian symbols of the owl and Athena.

When Pericles came to power in 460 B.C.E., the Athenians were trying to extend their power and influence in mainland Greece while also supporting a major revolt against the Persians in Egypt. However, Athens overextended itself in these ventures that, after initial successes, both failed miserably. Sparta led a coalition of Greeks to stop Athens' expansion in Greece, while the Persians trapped and destroyed a large Athenian fleet on the Nile by diverting the course of the river and leaving the Athenian ships stuck in the mud. As a result, Pericles abandoned Egypt to the Persians, left the rest of mainland Greece to the other Greeks, and restricted Athens' activity to consolidating its hold on its Aegean empire. By 445 BC, peace Persia and Sparta, recognizing each others' spheres of control allowed Athens to concentrate on more cultural pursuits which flourished in a number of areas.

In sculpture, the severe classical style succeeded the stiffer Archaic style after the Persian Wars. One key to this was the practice, known as contrapposto, of portraying a figure with its weight shifted more to one foot than the other, which, of course is how we normally stand. The body was also turned in a more naturalistic pose and the face was given a serene, but more realistic expression. The severe style was quite restrained and moderate compared to later developments, expressing the typical Greek belief in moderation in all things, whether in art, politics, or personal lifestyle. The overall result was a lifelike portrayal of the human body that seemed to declare the emergence of a much more self assured humanity along with Greek independence from older Near Eastern artistic forms. Other art forms showed similar energy and creativity.

In architecture, Pericles used the surplus from the league treasury for an ambitious building program, paid for with funds from the league treasury to adorn Athens' Acropolis. This also provided jobs for the poor, resulting in widespread popular support for Pericles' policies. Foremost among these buildings was the Parthenon. Constructed almost entirely of marble (even the roof) it is considered the pinnacle of Classical architecture with its perfectly measured proportions and simplicity. Ironically, there is hardly a straight line in the building. The architects, realizing perfectly straight lines would give the illusion of imperfection, created slight bulges in the floor and columns to make it look perfect. Although in ruins from an explosion in 1687 resulting from its use as a gunpowder magazine, the Parthenon still stands as a powerful, yet elegant testament to Athenian and Greek civilization in its golden age.

Another important, if less spectacular art form that flourished at this time was pottery. Around 530 B.C., the Greeks developed a new way of vase painting known as the red figure style. Instead of the earlier technique of painting black figures on a red background (known as the black figure style), potters put red figures on a black background with details painted in black or etched in with a needle. This technique, combined with the refined skills of the vase painters' working on such an awkward surface, gave Athenian pottery unsurpassed beauty and elegance, putting it in high demand throughout the Mediterranean.

In addition to its artistic value, Athenian pottery provides an invaluable record of nearly all aspects of Greek daily life, especially ones of which we would have little evidence otherwise, such as the lives of women, working conditions and techniques of various crafts, and social (including sexual) practices. Given these themes and the large number of surviving pieces, Greek pottery also reflected the more democratic nature of Greek society, since it was available to more people than had been true in earlier societies where high art was generally reserved for kings and nobles with the power and wealth to command the services of artisans.

Possibly the most creative expression of the Greek genius at this time was in the realm of tragic and comic drama, itself a uniquely Greek institution. While still sacred to the god of wine and revelry, Dionysus, Greek drama at this time developed into a vibrant art form that also formed a vital aspect of public discourse on contemporary problems facing the Athenian democracy. However, being part of a state supported religious festival still overtly concerned with religious or mythological themes, the tragedians' expressed their views indirectly by putting new twists on old myths. This kept discussion of the themes treated in the plays on a more remote and philosophical level. That, in turn, allowed the Athenians to reflect on moral issues that were relative to, if not directly about, current problems that they could then understand and deal with more effectively.

For example, Sophocles' Oedipus the King on one level was about flawed leadership which, no matter how well intentioned, could lead to disastrous results, in this case a plague afflicting Thebes for some mysterious reason. However, this play was produced soon after a devastating plague had swept through Athens and killed its leader, Pericles, who had led Athens into the Peloponnesian War. must have given the Athenians watching it reason to reflect on their own similar problems and what had caused them.

Greek comedy was best represented by Aristophanes, sometimes referred to as the Father of Comedy. Whereas Greek tragedians expressed their ideas with some restraint, comedy cut loose practically all restraints in its satirical attacks on contemporary policies, social practices, and politicians. Where else, in the midst of a desperate war, could one get away with staging such anti-war plays as Lysistrata, where the women of warring Athens and Sparta band together in a sex strike until the men come to their senses and end the war?

Such freedom of expression was also found in the realm of philosophy. We have seen how the most famous philosopher of the time, Socrates, "called philosophy down from the skies" to examine moral and ethical issues. In addition to Socrates, there arose a number of independent thinkers, referred to collectively as the Sophists, who were drawn to Athens' free and creative atmosphere. Inspired by the rapid advances in the arts, architecture, urban planning, and sciences, they believed human potential was virtually unlimited, One Sophist, Protagoras, said that, since the existence of the gods cannot be proven or disproven, Man is the measure of all things who determines what is real or not. This opened the floodgates to a whole variety of new ideas that also challenged traditional values. In his play, The Clouds, Aristophanes mercilessly satirized the Sophists as men who boasted they could argue either side of an argument and make it seem right. This belief that there is no real basis for truth would especially affect a younger generation of Athenians. Some of them, ungrounded in any sense of values, would mistake cleverness for wisdom and lead Athens down the road to ruin.

It is incredible to think that Western Civilization is firmly rooted in this short, but intense outpouring of creative energy from a single city-state with perhaps a total of 40,000 citizens. However, Athens' golden age would be short-lived as growing tensions would trigger a series of wars that would end the age of the polis.