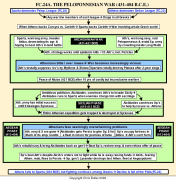

FC24A: The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE)

Flowchart

The conflict that triggered the long collapse of the polis was the Peloponnesian War. It started when Athens, wanting to control trade to the west with Southern Italy and Sicily, helped Corcyra in a dispute with its founding city, Corinth. In retaliation, Corinth helped another of its former colonies, Potidaea, in a revolt against Athens and also turned to Sparta for help. This prompted Athens' leader, Pericles, to issue the Megarian Decree, cutting off all the empire's trade with another Spartan ally, Megara. As Megara joined Corinth in pressuring Sparta to take action against Athens, war fever grew on both sides.

In 431 B.C.E., as war with Sparta loomed, Euripides (485-406 B.C.E.), the third of the great tragic playwrights staged

Medea., Its title character, the barbarian princess who had helped Jason get the Golden Fleece, is rejected by Jason in favor of a more desirable marriage to a princess of Corinth.

Medea exacts a grisly revenge, murdering, not only Jason's new bride, but her own children to keep them from her enemies. At the end of the play, however, she is granted asylum in

Athens. Did

Medea represent the Athenians' own ruthlessness as they prepared for war, or possibly the civil strife in Corcyra that Athens had recently allied with against its enemy, Corinth?

Either way, Euripides' closing lines warn the Athenians against the uncertainty of the future:

Many things are determined by Zeus on Olympus, and many wishes are unexpectedly granted by the gods. But many things we expect to happen do not come to pass, for the gods continue to

bring about what we did not expect.

Euripides' warning went unheeded and war was declared.

Our main source for the period is Thucydides, whose History of the Peloponnesian War set the standard for historical accuracy and impartiality until the modern era. His history is especially valuable for its portrayal of the psychological effects of war on the human spirit. And just as the plays of the time let us use tragedy as history, Thucydides' account of the prolonged agony of the Peloponnesian War presents history as a form of tragedy. His history along with the tragic dramas of the time and Aristophanes' satirical comedies chronicle the long descent into madness that seemed to overtake the Athenians as the war dragged on.

Since Sparta was a land power and Athens was a naval power, Pericles, decided to rely on the navy to protect the empire and raid the coasts of the Peloponnesus. When the Spartans marched into Attica, he would pull the rural population inside the Long Walls, abandoning the countryside to the enemy until they left. As long as its grain routes were open, Athens should be able to hold out until Sparta tired of the war and gave up.

It was not easy to convince the Athenians to leave the countryside and passively watch from the Long Walls as their homes and fields went up in flames. However, Pericles' policy might have worked except for one thing that he had not counted on. In the second year of war, an epidemic broke out in Athens. Ordinarily, any epidemic would have been bad enough, but the crowded and unsanitary conditions of Athens under siege in the heat of summer intensified its effects. Thucydides gives a frightening account of the disease:

“The crowding of the people out of the country into the city aggravated the misery; and the newly arrived suffered most. For, having no houses of their own, but inhabiting in the height of summer stifling huts, the mortality among them was dreadful, and they perished in wild disorder. The dead lay as they had died, one upon another, while others hardly alive wallowed in the streets and crawled about every fountain craving for water. The temples in which they lodged were full of the corpses of those who died in them; for the violence of the calamity was such that men, not knowing where to turn, grew reckless of all law, human and divine. The customs that had hitherto been observed at funerals were universally violated, and they buried their dead each one as best he could. Many, having no proper appliances, because the deaths in their household had been so frequent, made no scruple of using the burial-place of others. When one man had raised a funeral pyre, others would come, and throwing on their dead first, set fire to it; or when some other corpse was already burning, before they could be stopped would throw their own dead upon it and depart.

“There were other and worse forms of lawlessness which the plague introduced at Athens. Men who had hitherto concealed their indulgence in pleasure now grew bolder. For, seeing the sudden change, how the rich died in a moment, and those who had nothing immediately inherited their property, they reflected that life and riches were alike transitory, and they resolved to enjoy themselves while they could, and to think only of pleasure...for offenses against human law no punishment was to be feared; no one would live long enough to be called to account. Already a far heavier sentence had been passed and was hanging over a man's head; before that fell, why should he not take a little pleasure? (II,48-49; 52-53)

Among the epidemic's victims was Pericles whose moderate and reasonable leadership would be sorely missed by Athens. Afterwards, men of much narrower vision would guide the polis on less trustworthy paths, and eventually to ruin. Soon afterwards, Sophocles staged Oedipus the King, considered by many as the greatest of Greek tragedies. Taking place in Thebes that is also suffering from a mysterious plague, an oracle says the murderer of the previous king, Laius, must be found and punished. The present king, Oedipus, who does not realize he himself unwittingly had killed Laius years before, launches an investigation. When Oedipus finally realizes he is the killer, he blinds himself and goes into exile to free Thebes from the curse. Given the time it was written, one could see Sophocles comparing Pericles to Oedipus, both being great leaders with the best intentions for their respective cities. However, some fatal unforeseen flaw in each leads, however unjustly, to disaster. The play ends with a somber warning by the chorus on the uncertainty of life:

“People of Thebes, my countrymen, look on Oedipus

He solved the famous riddle with his brilliance,

he rose to power, a man beyond all power.

Who could behold his greatness without envy?

Now what a black sea of terror has overwhelmed him.

Now as we keep our watch and wait the final day

count no man happy till he dies, free of pain at last.”

The first phase of the struggle, known as the Archidamian War, lasted ten years and became increasingly vicious the longer it lasted. Athens brutally put down revolts by the city-states, Mytiline and Skione, totally destroying the latter when it fell. Likewise, Thebes besieged and finally destroyed Athens' ally, Plataea, which had bravely stood by Athens at the Battle of Marathon sixty years earlier. Thucydides gives a grim analysis of the effects of war and the resulting civil strife within the various city-states:

“In peace and prosperity, both states and individuals are more generous, because they are not under pressure; but war, which cuts down the margin of comfort in daily life, is a teacher of violence, and assimilates ordinary people's characters to their conditions.

“Revolution now became endemic;.… even the former prestige of words was changed. Reckless daring was counted the courage of a good party man; prudent hesitation cowardice in disguise; moderation, a cover for weakness, and the ability to see all sides, inability to do anything...The bitter speaker was always trusted, and his opponent held suspect. The successful conspirator was reckoned intelligent, and he who detected a plot more brilliant still, but he who planned not to need such methods was accused of splitting the party and being afraid of the enemy...

“The tie of party took precedence over that of the family;...Most people would rather be called clever knaves (if knave is what they are) than honest fools; they are ashamed of the latter label, but proud of the former.

“The cause of the whole trouble was the pursuit of power for the sake of greed and personal ambition...Leaders everywhere used honorable slogans—'political equality for the masses' or 'the rule of a wise elite'; but the commonwealth which they served in name was the prize that they fought for...And moderate men fell victims to both sides...And the cruder intellects generally survived better; for conscious of their deficiencies and their opponents' cleverness, and fearing that they might get the worst of it in debate and be victims of some cunning plot if they delayed, they struck boldly and at once; but the others, contemptuously sure that they could see danger in time and had no need to take by force what they could get by wit, were more often caught off their guard and destroyed.”

At this time, comic drama, also sacred to Dionysus, was becoming increasingly popular in Athens, with two annual festivals, also sacred to Dionysus, being devoted to comedy. Whereas tragic drama skillfully veiled its messages in myth, Aristophanes, the most prominent of the comic playwrights, blatantly attacked his targets head-on, whether they be the war (during which he wrote numerous anti-war plays), social and political ills, specific public figures, or the Athenian democracy itself. Aristophanes, a conservative upset with the disturbing trends of the times, pulled no punches and, to the Athenians' credit, got away with it all. One of his favorite victims was the popular, but crude and brutal politician, Cleon the Tanner, whose character and tactics Thucydides seemed to be specifically describing in the passage cited above. Supposedly, when no actor could be found with the nerve to play Cleon in The Knights, Aristophanes himself played the role.

In Aristophanes' oldest surviving play, The Acharnians (425 B.C.E.), Dicaeopolis, a farmer ruined by the war, makes a separate peace with Sparta. The resulting prosperity (including wine and dancing girls) for Dicaeopolis and his neighbors is contrasted with a returning general who has only wounds to show for his efforts.

The Knights (424 B.C.E.) raked both Cleon and the Athenian democracy over the coals. Lord Demos ("Democracy") has two slaves, Nicias and Demosthenes (two conservative politicians) who are ruled by the cruel overseer, the Paphlagonian leather monger, an obvious reference to Cleon the Tanner. The two slaves recruit a crude sausage seller, Agoraritus, who engages Cleon in a shameless bribery contest for the favor of Lord Demos, offering cheap fish, fresh rabbit meat, pillows for the stone assembly seats, and even world dominion. Agoracritus finally wins by offering the aged Lord Demos renewed youth. Thus the democracy is revived as young, energetic, and statesmanlike just as in the good old days. This appeased the democratic audience that had been portrayed as old, conceited, and easily fooled. Cleon was not so lucky, being accused in the play of bribery, slander, lies, threatening opponents with the charge of treason, and false accusations. Coming at the peak of Cleon's popularity after he had won a victory over the Spartans and then arrogantly refused to make peace, The Knights helped deflate his ego and won Aristophanes first prize in the dramatic competition

In The Wasps (422 B.B.), Aristophanes took on the addiction many Athenians had to serving as jurors in the courts. He also lambasts Cleon who had raised the jurors' pay, largely funding the raise with fines and legal fees paid by political enemies whom he brought to court. As the chorus tells the jurors, "You deprive yourself of your own pay if you don't find the accused guilty." At another point the character, Philocleon ("Lover of Cleon"), himself a chronic juror, says " We are the only ones whom Cleon, the great bawler, does not badger. On the contrary he protects and caresses us; he keeps off the flies..." Philocleon's son, Bdelycleon ("Hater of Cleon") finally breaks his father's addiction to the courts by letting him stage mock trials at home. In one he tries the family dog, Labes, for stealing some cheese. A second dog testifies against Labes, saying he refused to share the cheese. Bdelycleon, defending Labes, brings in her puppies, urging them to "yap up on your haunches, beg and whine" to win the court's sympathy (a common tactic then). Philocleon at last acquits the dog.

Disaster and Collapse (421-404 B.C.E.)

After Cleon was killed in battle, peace was signed with Sparta in 421 B.C.E. Neither side gained anything, supposedly returning any lands taken during the war. However, neither side abided by these terms, keeping tensions high and the likelihood of a lasting peace correspondingly low. In 417 B.C.E. Athens attacked the small island state of Melos for no good reason. Thucydides' dialogue between Melian and Athenian delegates reveals how deeply the Athenians had become corrupted by power:

“Athenians: Well, then, we Athenians will use no fine words; we will not go out of our way to prove at length that we have a right to rule, because we overthrew the Persians; or that we attack you now because we are suffering any injury at your hands. We should not convince you if we did; nor must you expect to convince us by arguing that, although a colony of the Lacedaemonians (Spartans), you have taken no part in their expeditions, or that you have never done us any wrong. But you and we should say what we really think, and aim only at what is possible, for we both alike know that into the discussion of human affairs the question of justice only enters where the pressure of necessity is equal, and that the powerful exact what they can, and the weak grant what they must...And we will now endeavor to show that we have come in the interests of our empire, and that in what we are about to say we are only seeking the preservation of your city. For we want to make you ours with the least trouble to ourselves, and it is for the interest of us both that you should not be destroyed.

Melians: It may be your interest to be our masters, but how can it be ours to be your slaves?

Athenians: To you the gain will be that by submission you will avert the worst; and we shall be all the richer for your preservation.

Melians: But must we be your enemies? Will you not receive us as your friends if we are neutral and remain at peace with you?

Athenians: No your enmity is not half so mischievous to us as your friendship; for the one is in the eyes of our subjects an argument of our power, the other of our weakness.

Melians: But are your subjects really unable to distinguish between states in which you have no concern, and those which are chiefly your own colonies, and in some cases have revolted and been subdued by you?

Athenians: Why, they do not doubt that both of them have a good deal to say for themselves on the score of justice, but they think that states like yours are left free because they are able to defend themselves, and that we do not attack them because we dare not. So that your subjection will give us an increase of security, as well as an extension of empire. For we are masters of the sea, and you who are islanders, and insignificant islanders too, must not be allowed to escape us.”

When Melos fell in 415 B.C.E. the Athenians mercilessly slaughtered the men and enslaved the women and children. Euripides expressed his outrage at this reckless abuse of power in The Trojan Women, possibly the most powerful statement until modern times on the senseless suffering caused by war. The scene is Troy after its brutal destruction as seen through the eyes of the victims, the various Trojan women being parceled out as slaves to different Greek warriors. One by one, they learn of their individual fates, including the murder of Hector's baby son, Astyanax. Poseidon at the start of the play utters a grim warning to the Greeks for their sacrileges in the sack of Troy, but one that could as well apply to the Athenians for their recent actions: "How are ye blind, ye treaders down of cities, ye that cast temples to desolation and lay waste tombs, the untrodden sanctuaries where lie the ancient dead; yourselves so soon to die!"

Convincing the Athenians to carry out the horrible massacre of the Melians was Alcibiades, a brilliant and handsome young politician and former student of Socrates. We have already seen how clever, although lacking in perspective, this young man was in the dialogue with his uncle Pericles on the definition of law. He was equally unscrupulous in his pursuit of power and publicity, at one point entering seven chariots in the Olympics and at another buying a very expensive dog and cutting off its tail so people would talk about him.

The Sicilian Expedition

In 415 B.C.E. Alcibiades convinced the Assembly to invade Sicily, blinding them to the realities and difficulties of the undertaking with the lure of untold riches. Therefore, the Athenians, sent a large fleet and army under Alcibiades and Nicias (who was opposed to the expedition to start with). Alcibiades might have carried out the whole scheme if he had been allowed to. However, he was summoned home on what were probably trumped up charges of defacing some statues sacred to Hermes. Instead of facing a hostile jury, he jumped ship, went to Sparta, and convinced it to declare war on Athens while it was occupied in Sicily.

All this left Nicias in command in Sicily. Considering his lack of enthusiasm and slow-moving, superstitious ways, he made remarkable success, besieging Syracuse and almost cutting it off from outside help. However, Nicias' failure to act quickly let the Syracusans turn the tables on him, and soon it was the Athenians who were in danger of being cut off from escape. A second army and fleet came to relieve Nicias' force, but soon they too found themselves in a trap that was quickly closing. Unfortunately, a lunar eclipse caused the superstitious Nicias to wait twenty-seven days before letting the Athenians make their move. By then it was too late. After a desperate and futile effort to break out of Syracuse's harbor, the Athenians abandoned their waterlogged fleet and tried to escape overland. The army, demoralized by defeat and decimated by hunger, thirst, and disease, came to an end in a pathetic mob scene described by Thucydides.

“When the day dawned Nicias led forward his army, and the Syracusans and the allies again assailed them on every side, hurling javelins and other missiles at them. The Athenians hurried on to the river Assinarus. They hoped to gain a little relief if they forded the river, for the mass of horsemen and other troops overwhelmed and crushed them; and they were worn out by fatigue and thirst. But no sooner did they reach the water than they lost all order and rushed in; every man was trying to cross first, and, the enemy pressing upon them at the same time, the passage of the river became hopeless. Being compelled to keep close together they fell one upon another, and trampled each other under foot; some at once perished, pierced by their own spears; others got entangled in the baggage and were carried down the stream. The Syracusans stood upon the further bank of the river, which was steep, and hurled missiles from above on the Athenians, who were huddled together in the deep bed of the stream and for the most part were drinking greedily. The Peloponnesians came down the bank and slaughteed them, falling chiefly upon those who were in the river. Whereupon the water at once became foul but was drunk all the same, although muddy and dyed with blood, and the crowd fought for it.”

Nearly all the Athenians were either killed or captured by the Syracusans. Because of their great number, the prisoners were kept in a quarry where exposure to the elements killed most of them off. Some who could recite passages from Euripides' plays, which were popular in Syracuse, were rescued by rich families. These who eventually returned home made a point of thanking Euripides for saving their lives..

Athens' comeback and final fall (413-404 B.C.E.)

Hardly an Athenian family was left untouched by the Sicilian disaster, while Athens itself had lost two fleets and armies. Now trouble piled on top of trouble as much of Athens' empire rose up in revolt. Thanks to Alcibiades, the Spartans now continuously occupied a fort in Attica to keep the Athenians huddled behind their Long Walls. Worst of all, Alcibiades had arranged for the Spartans to ally with Persia, getting Persian money and ships in return for promising to turn Ionia over to the Great King. An oligarchic revolution even briefly replaced Athens' democracy.

Despite these adversities, the Athenians bounced back, scraping together enough money and men to build a new fleet and carry on the war for nine more years. Alcibiades even returned to the graces of the Athenians and led their fleet to several decisive victories that at least partially restored Athens' crumbling empire. On two different occasions, Sparta even asked for peace, and was twice turned down by the Athenians, a foolish response since Persia could easily rebuild any Spartan fleets the Athenians destroyed.

In the midst of all this Aristophanes produced possibly his most outrageous, and profound statement on the war, Lysistrata in 411B.C.E. In it the main character, Lysistrata ("she who disbands armies") organizes the women of Athens and Sparta, who are all sick of the war, to stage a sex strike and seize the treasury on the Acropolis until the men agree to make peace. The lowly women, who abound in common sense, triumph, and peace is happily made. Unfortunately, in real life, the war went on.

Another crisis erupted when an old drinking friend of Alcibiades, whom he had irresponsibly left in command of the fleet during his absence, offered battle against orders and was defeated. The Athenians, blaming Alcibiades, exiled him a second time. With him went Athens' best chance to win the war. In 406 B.C.E., stormy conditions after an Athenian victory at Arginusae prevented the rescue of several thousand shipwrecked Athenians. The mob blamed the six Athenian generals in charge of the fleet and had them tried and executed.

These events inspired Euripides' frightening portrayal of human madness, The Bacchae, produced a year after his death in 406 B.C.E. In it Dionysus returns to Thebes and incites wild frenzies in the forest by the local women who become his followers, the Maenads. When the king, Pentheus, who represents civilized rationality, tries to save Thebes from the wild irrational Dionysiac rites, he is torn apart by the Maenads. Madness reigns supreme as his own mother returns to town with his head on a stick, thinking it is a lion. Greek audiences must have been especially shaken as they watched the one thing on which they especially prided themselves, their moderate rationality, drowning in a sea of madness, whether on stage or in war.

Unlike the earlier days when the playwrights could help guide the democracy on a wise course, it seemed they could no longer offer guidance through the morass of problems Athens had gotten itself into. Now they could only point out the shocking failure of its leaders and assembly in the policies they pursued. And after the deaths of Euripides and Sophocles, there seemed to no playwrights with the talents to do that.

Therefore, in Aristophanes' play, The Frogs, Dionysus goes down to Hades to retrieve a good playwright from the dead. A poetry contest between Aeschylus and Euripides, with the verses weighed on a cheese scale, ensues to decide who gets to return to earth. Aeschylus wins first place and Sophocles gets second, even though he is not even in the contest. The play ends with the chorus of frogs escorting Aeschylus back to earth, urging him to “heal the sick state, fight the ignoble, cowardly, inward foe, and bring us peace.”

However the Athenians continued to ignore the wiser counsels of their playwrights. In 405 B.C.E. they built one last fleet, paying for it by stripping the gold from the temples and statues. However, a clever Spartan general, Lysander, lulled the Athenian generals into a false sense of security and then destroyed their fleet in a surprise attack at Aegospotami. Athens fell the next year after a long desperate siege. The Long Walls were torn down and its empire was stripped away, although Sparta did spare the city from destruction, probably as a counterweight against the rising power of Thebes. The democracy was replaced by an oligarchy of thirty men led by another of Socrates' old students, Critias, who conducted a vicious reign of terror.

Several years later, the Athenians were able to restore their independence, democracy and even the Long Walls. However, peace was no more in sight than it had been twenty-seven years before. In 399 B.C.E., Socrates was tried and executed for corrupting the youth of the city with his teachings. That event, as much as any, symbolized the end of Athens' cultural golden age.