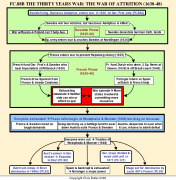

FC88B: The later stages of the 30 Years War (1631-48)

Flowchart

The Swedish Phase

At this point Sweden, prodded by fear of Austria's growing power, Spain's apparent weakness, and France's willingness to back it with money, threw in its lot against the Hapsburgs and invaded Germany. This transformed what was already a European wide affair into a prolonged and bloody war of attrition where neither side was able to win a quick decisive victory or willing to concede defeat. To the German people caught in the middle, the war seemed to have assumed a life of its own that would carry on until there was nothing left in Germany to sustain it.

Sweden was a relative newcomer to European diplomacy. However, thanks to a line of brilliant and ambitious kings, the "Swedish meteor" would shine brightly over the Baltic before burning out in the 1700's. Two other Baltic states, Poland and Russia, were also assuming a greater role in European affairs. As a result, events in Eastern Europe and the Baltic had a growing impact on events in Western Europe. At this point, it was peace between Sweden and Poland that freed Sweden to invade Germany.

Sweden's king, Gustavus Adolphus, was a brilliant and daring general with a highly trained and disciplined army at his back. He used Swedish draftees rather than unreliable mercenaries and put them in smaller units that could more effectively use their numbers and firepower. He further increased this firepower by experimenting with mobile field artillery that could wreak havoc on the massed formations of the day. These reforms proved their worth at the battle of Breitenfeld (1631) where Swedish discipline and firepower overcame the desertion of their Saxon allies to crush an imperial army under Tilly. The next year Swedish tactics won a bloody but costly victory at Lutzen. In the smoke and confusion of battle, Gustavus was killed, taking a good part of the heart out of the Swedish effort.

Nevertheless, the Swedes pressed on, devastating Catholic lands on the way. Austria enticed its ally and Sweden's enemy, Poland, into the war, but a war further east against Russia neutralized the Poles. This prompted Spain to send an army north to retrieve the situation in Germany and the Netherlands. In 1634, the Spanish army crushed the Swedes at Nordlingen. The Swedes launched some fifteen heroic, but basically suicidal charges against the Spanish positions, all with disastrous results.

The war of attrition (1635-48)

Once again, the Protestant cause seemed on the verge of collapse. The war had raged now for some sixteen years. Hundreds of German towns and villages were devastated, and whole regions were virtually depopulated. The war's destruction and upheaval brought famine, and with that came disease. Germany was ready for peace. Unfortunately, the other powers in Europe were not. Instead, the war was about to enter a much more destructive phase of attrition where each side, instead of expecting a quick and decisive victory, fought to wear down the other side no matter what the cost might be to themselves.

In 1635, France wholeheartedly entered the war, ending any hopes for a quick peace. Its strategy was still largely to fund two of Spain's enemies, the Dutch and Swedes, and let them do as much of the fighting as possible. At first its own armies were somewhat ineffective against Spain's veteran troops. However, the Swedes, bolstered by French funds, beat the imperialists at Wittstock (1636) and forced an invading Spanish army to withdraw from France. This in turn allowed the French to invade Spain to support a revolt in Catalonia.

Meanwhile, the Dutch had dealt a crippling blow to the Spanish war effort by destroying a Spanish armada of 77 ships at the Battle of the Downs (1639). The next year, the Dutch crushed another Spanish and Portuguese fleet off the coast of Brazil. These two naval battles had the double effect of permanently wrecking Spanish naval power in the Atlantic and triggering a Portuguese revolt.

Even for the victors, this war was exhausting and ruinous, and by 1640 most powers were ready for peace. However, several things prevented peace at this time. First of all, the tangled alliances kept any one power on one side from negotiating its own separate peace. Second, rulers had a limited resource base with which to pay for the war, and that was shrinking steadily as the war's destruction ate up those resources. This helped generate the vicious cycle of stalemate discussed above.

However, with each year, the tide of war was shifting more and more against the Hapsburgs. In Germany, the Swedes beat an Imperialist army at the Second Battle of Breitenfeld (1642), which caused most of Austria's German allies to desert it. In 1643, the French crushed a Spanish army at Rocroi, opening the way to invade the Spanish Netherlands and establish France as the premier power in Europe for decades.

With Spain on the verge of bankruptcy and collapse, Sweden's manpower depleted, and even France facing tax revolts, everyone agreed to start negotiations at Westphalia in 1645. Even then, heavy French and Swedish demands for land and money, Austrian reluctance to give up, and the fact that neutral Germany was the battleground caused the negotiations to drag out as the war dragged on.

End of the war and its results

In 1648, the Dutch finally made a separate peace with Spain, gaining recognition of their independence after an 80-year struggle (1567-1648). This and the growing threat of revolt in its own lands prompted France at last to come to terms that same year. The resulting treaty became known as the Peace of Westphalia.

The Peace of Westphalia symbolized and confirmed the great changes taking place in Europe's balance of power over the first half of the 1600's. Spain, bankrupt and exhausted, was now reduced to the level of a second-class power. Austria's influence was virtually destroyed in the Holy Roman Empire. However, it would find new life by expanding eastward against an even more corrupt and decaying power, the Ottoman Turks. Germany, whose population and property had suffered damages only surpassed by that of World War II, remained hopelessly broken into some 300 states. Yet out of the ashes of this destruction Brandenburg-Prussia would gradually emerge to unify Germany in 1871.

There were winners. Sweden emerged as the dominant power in the Baltic for another half century. However, by the early 1700's, its aggressive policies would wear it out and knock it out of the mainstream of European politics. The Dutch came out of the war in the best shape of any country in Europe. Dutch trade and economy actually flourished during the war, making enormous profits from raiding Spanish shipping, taking over Spain's colonial trade, and selling munitions to the various combatants, including Spain.

Politically, France was the big winner, severely weakening the ring of Hapsburg powers surrounding it as well as gaining territories along the Rhine. All this also had its cost. For one thing, France's war with Spain dragged on until 1659. Secondly, the terrible tax burden of the war triggered a revolt known as the Fronde (1648-53) that nearly toppled the monarchy of the young Louis XIV. As it was, Louis' monarchy emerged triumphant (unlike its counterpart in England also facing revolution), and France emerged as the dominant power in Europe. The age of Spain was giving way to the age of France.